The text that follows is a PREPRINT.

Please cite

as:

Fearnside,

P.M. 1987. Causes of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. pp. 37-53 In: R.F.

Dickinson (compilador) The Geophysiology of Amazonia: Vegetation and Climate

Interactions. John Wiley & Sons, New York, U.S.A. 524 pp.

Copyright: John

Wiley & Sons, New York, U.S.A.

The original publication is available from: John Wiley

& Sons, New York, U.S.A.

THE

CAUSES OF DEFORESTATION IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON

Philip M. Fearnside

Department of Ecology

National Institute for

Research in the Amazon

(INPA)

Caixa Postal 478

Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil

20 November 1984

Revised: 14 April 1985

Paper

presented at the United Nations University International Conference on

Climatic, Biotic and Human Interactions in the Humid Tropics: Vegetation and

Climate Interactions in Amazonia. 25 February ‑ 1 March 1985, São José

dos Campos ‑ São Paulo, Brazil.

To

appear in: Dickinson, R.E. (ed.) Geophysiology

of Amazonia John Wiley and Sons, New

York.

The present rate and probable future course of

forest clearing in Brazilian Amazonia is closely linked to the human use

systems that replace the forest. These

systems, including the social forces leading to particular land use

transformations, are at the root of the present accelerated pattern of

deforestation and must be a key focus of any set of policies designed to

contain the clearing process. The

present extent and likely changes in the various agricultural systems found in

the region are reviewed elsewhere (Fearnside, nd-a). Cattle pasture is by far the dominant land

use in cleared portions of the terra firme (unflooded uplands), not only

in areas of large cattle ranches, such as southern Pará and northern Mato

Grosso, but also in areas initially felled by smallholders for slash-and-burn

cultivation of annual crops, such as the Transamazon Highway colonization areas

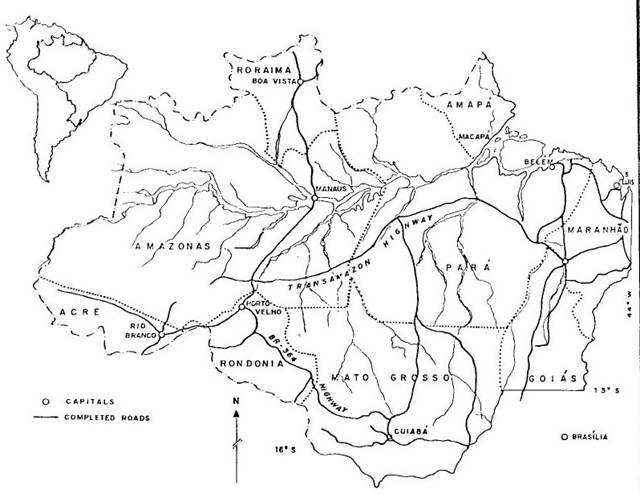

in Pará (Fig. 4.1). Pasture is even

dominant in areas like Rondônia where government programs have intensively

promoted and financed cacao and other perennial crops (Léna, 1981; Furley and

Leite, nd). The forces leading to

continued increase in pasture area, despite the low productivity and poor

prospects for sustainability of this use system, are those that most closely

affect the present rate of deforestation.

The extent and rate of deforestation in

Brazil's Amazon rainforest is a subject of profound disagreement among both

scholars and policy makers in Brazil and elsewhere. Equally controversial is the question of

whether or not potential future consequences of deforestation are sufficient to

justify the immediate financial, social, and political costs of taking measures

to contain the process. The lack of

effective policies to control deforestation in the Amazon today speaks for both

the preference among decision makers for minimizing such concerns and the

strength of forces driving the deforestation process. Here it is argued that deforestation is rapid

and its potential impact severe, amply justifying the substantial costs of speedy

government action needed to slow, and at some point stop, forest clearing.

4.1 EXTENT AND RATE OF DEFORESTATION

The vast areas of as yet undisturbed forest

in the Brazilian Amazon frequently lead visitors, researchers, and government

officials to the mistaken conclusion that deforestation is a minor concern

unlikely to reach environmentally significant proportions within the

"foreseeable" future. Such

conclusions are unwarranted; they also have the dangerous effect of decreasing

the likelihood that timely policy decisions will be made with a view to slowing

and limiting the process of deforestation.

Not only is better monitoring information needed for describing the

process, but also better understanding of underlying causes of

deforestation. Such understanding would

allow more realistic projections of future trends under present and alternative

policy regimes, and permit identification of effective measures to control the

process.

The most recent available survey of

deforestation covering the entire Brazilian Amazon was made by Brazil's

National Institute for Space Research (INPE) based on LANDSAT satellite images

taken in 1978 (Tardin et al., 1980).

The same study also interpreted images from 1975. The survey's finding that only 1.55% of the

area legally defined as Amazonia had been deforested up to 1978 contributed to

the popular portrayal in Brazil of deforestation as an issue raised only by

"alarmists." The INPE figure

underestimates clearing because of the inability of the technique to detect

"very small" clearings and of the difficulty of distinguishing second

growth from virgin forest. For example,

the Zona Bragantina, a 30,000 km2 region surrounding the town of Bragança in

northeastern Pará that was completely deforested in the early years of this

century (Egler, 1961; Sioli, 1973), is larger than the area indicated by 1975

images analyzed in the INPE study as deforested in Brazil's entire Legal

Amazon, and is almost four times the area indicated as cleared in the state of

Pará (Fearnside, 1982). Regardless of

any underestimation due to image interpretation limitations, the conclusion

that the area cleared through 1978 was small in relation to the 4,975,527 km2

Legal Amazon is quite correct.

Unfortunately, the small area cleared by

1978 is a far less important finding than another less publicized one apparent

from the same data set (Carneiro et al., 1982): the explosive rate of

clearing implied by comparing values for cleared areas at the two image dates

analyzed, 1975 and 1978. If the growth

pattern over the region as a whole was exponential during this period, the

observed increase in cleared area from 28,595.25 to 77,171.75 km2

implies a growth rate of 33.093% year-1, and a doubling time of only

2.09 years. Deforestation rates vary widely

in different parts of the region, being highest in southern Pará, northern Mato

Grosso, and in Rondônia and Acre. An

analysis of a longer time series of LANDSAT images from one of these areas,

Rondônia, is presented elsewhere (Fearnside, 1982). Comparisons of cleared areas for 1973, 1975,

1976, and 1978 in two areas of government‑sponsored colonization by

farmers with 100 ha lots, and in two areas dominated by 3000 ha cattle ranches,

indicate that deforestation in these areas may have been progressing in an

exponential fashion during the period, although data are too few for firm

conclusions (Fearnside, 1982).

LANDSAT image interpretation by the

Brazilian government for the state of Rondônia as a whole (243,044 km2) indicates

that cleared areas rose from 1,216.5 km2 in 1975 (Tardin et al., 1980)

to 4,184.5 km2 in 1978 (Tardin et al., 1980) to 7,579.3 km2

in 1980 (Carneiro et al., 1982) to 13,955.2 km2 in 1983

(Brazil, Ministério da Agricultura, 1985; Fearnside and Salati, nd). The cleared area therefore increased from

0.50% to 3.12% of Rondônia's total area in only five years, and jumped to 5.74%

in the succeeding three years. It should

be remembered that limitations of the image interpretation methodology mean

that the true cleared areas were probably larger than these numbers imply. Even with this limitation, the clearing

estimates reveal not only that deforestation proceeded rapidly throughout the

period, but that it showed no signs of slowing as of 1980 (Fig. 4.2) and

continued through 1983 at a faster-than-linear pace.

LANDSAT data from 1980 images (Brazil,

Ministério da Agricultura, IBDF, 1983) reveal that strong exponential growth in

cleared areas over the 1975-1980 period also occurred in Mato Grosso and Acre,

while increase was roughly linear in Pará, Maranhão and Goiás (Fearnside,

1984a, nd-b). No 1980 data are yet

available for Roraima, Amazonas or Amapá.

Some of the forces behind deforestation are

linked to positive feedback processes, which can be expected to produce

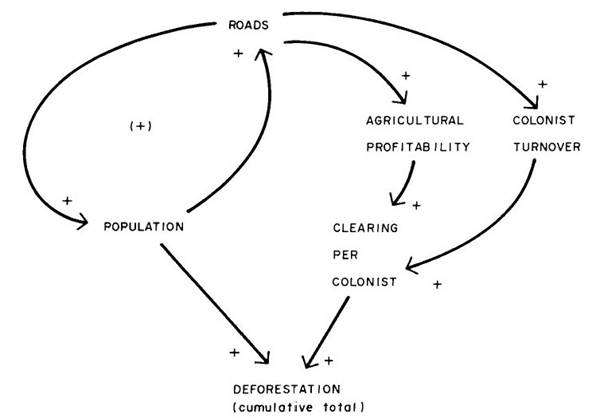

exponential changes. Roadbuilding, for

example, is closely tied to the rate of arrival of new immigrants: more and

better roads attract more immigrants, while the presence of a larger population

justifies the construction of still more and better roads (Fig. 4.3). In Rondônia the population has been growing

even more rapidly than in other parts of the region because of the flood of new

immigrants from southern Brazil (Fig. 4.2).

Projections of unchanging exponential rates for deforestation into the

future, even in deforestation foci like Rondônia, are hazardous as anything but

illustrations because there are many other factors affecting the process. As the relative importance of different

factors shifts in future years, some of the changes will serve to increase

deforestation rates, while others will slow them. Within completely occupied blocks of colonist

lots, for example, clearing of virgin forest proceeds roughly linearly for

about six years, after which a plateau is reached (Fearnside nd-c). The rate at which an individual lot is

cleared is increased by such events as the arrival of road access and turnover

in the lot's occupants (Fearnside, 1980a, nd-c) (Fig. 4.3).

At present, regional scale clearing

statistics appear to be dominated by immigration, along with other forces that

accelerate deforestation such as the positive effect of improved road access on

market availability and land value appreciation. In the future, the behavior of the population

already established in the region should gain in relative importance. Other reasons for an eventual slowing (but

not halting) of clearing include poorer soil quality and inaccessability of

remaining unoccupied land, the finite capacity of source areas to supply

immigrants at ever increasing rates, decreased relative attractiveness of

Amazonia after this frontier of unclaimed land "closes," and limits

of available capital, petroleum and other inputs that would be necessary if

rates of felling should greatly increase (Fearnside nd-d). However, nothing short of a comprehensive

program of government actions based on conscious decisions can be expected to

contain deforestation before the region's forests are lost (Fearnside nd-b).

The accelerating course of deforestation

cannot be adequately represented by any simple algebraic formula such as the

exponential equation, nor can its eventual slowing be expected to follow a

smooth and symmetrical trajectory such as a logistic growth path. The complex interacting factors bearing on

the process are more appropriate for analysis with the aid of computer

simulation (Fearnside, 1983a). An idea

can be gained of the relationships of the factors involved by examining more

closely some of the causes of deforestation in Amazonia.

4.2 CAUSES OF DEFORESTATION

Present causes of deforestation can be

divided, somewhat artificially, into proximal causes (Table 4.1) and underlying

causes (Table 4.2). Proximal causes

motivate land owners and claimants to direct their efforts to clearing forest

as quickly as possible. The underlying

causes link wider processes in Brazil's economy either to the proximal

motivations of each individual deforester, or to increases in numbers of

deforesters present in the region.

Some of the principal motives for

deforestation apply most forcefully to large landholders, expecially those

motives connected to government incentive programs. These represent forces relatively easily

controlled by governmental actions, as has already occurred to a small degree

(see note, Table 4.1). Deforestation is

also linked to longstanding economic patterns in Brazil, such as high inflation

rates, which have shown themselves to be particularly resistant to government

control (Fig. 4.4).

Changes in agricultural patterns in

southern Brazil have had heavy impacts.

The rise of soybeans has displaced an estimated 11 agricultural workers

for every one finding employment in the new production system (Zockun,

1980). Sugarcane plantations, encouraged

by the government for alcohol production, have likewise expelled

smallholders. Replacement of labor‑intensive

coffee plantations with mechanized farms raising wheat and other crops, a trend

driven by killing frosts and relatively unfavorable prices, has further swollen

the ranks of Amazonian immigrants (Sawyer, 1982).

Within Amazonia, most evident are the

forces of land speculation (Fearnside, 1979a; Mahar, 1979), the magnifying

effect of cattle pasture on the impact of population (Fearnside, 1983b), and

the positive feedback relationship between roadbuilding and population

increases (Fearnside, 1982).

Profits from sale of agricultural

production are added to speculative gains, tax incentives and other forms of

government subsidy in making clearing financially attractive. Small farmers often come to the region intent

on making their fortunes as commercial farmers, but they gradually see the

higher profits to be made from speculation as their neighbors sell their plots

of land for prices that dwarf the returns realized from years of hard labor. Agriculture then becomes a means of meeting

living expenses while awaiting the opportunity of a profitable land sale and a

move to a more distant frontier.

Although individual variability is high, most aspire to produce enough

to live well by the standards of their own pasts while awaiting an eventual

sale. Farmers usually see such sales as

providing the reward for "improvements" made on the land during their

tenure, rather than as speculation.

Larger operators are more likely to begin their activities in the region

with speculation in mind but are likewise always careful to describe themselves

as "producers" rather than speculators.

Subsistence production is always a

contributor to forest clearing, although it is not presently the major factor

that it is in many other rainforest areas, as in Africa (Myers, 1980,

1982). The speculative and commercial

motives for clearing in Amazonia mean that the relationship of commodity prices

to clearing is positive for most of the farmers involved. In areas of the tropics where cash crops are

grown primarily for supplying subsistence needs, the relationship can be the

reverse: a positive feedback loop exists whereby falling prices for a product

mean that larger areas must be planted for the farmer to obtain the same subsistence

level of cash income, while the resulting increased supply of the product

further drives prices down (Gligo, 1980: 136; Plumwood and Routley, 1982). For most Amazonian farmers, however, desire

for cash so greatly exceeds the income-producing capacity of the farms that

only the restraints of available labor and capital limit the areas cleared and

planted (Fearnside, 1980b).

Future deforestation trends should reflect

changes in the balance of forces listed in Tables 4.1 and 4.2, as from

declining impact of new arrivals relative to the resident population. Future trends can also be expected to show

the effects of projected major developments (Table 4.3). As timber export, presently a negligible

factor, becomes more important, outright deforestation will be supplemented by

the often heavy disturbances following selective felling that presently

characterize much of the forest conversion in Asia and Africa. Charcoal production, expecially that derived

from native forest, is foreseen as a major factor in the southeastern portion

of the region in the coming decades.

Large firms, such as lumber companies

requiring marketable timber, or steel manufacturing industries requiring

charcoal, pose the additional problem of playing more active and forceful roles

in seeing that environmental conflicts of interest are resolved in their

favor. Chances are higher, as compared

to the case of relatively small investors, that concessions will be made at the

expense of previous governmental commitments to reserves of untouched

forest. This recently occurred in the

case of timber concessions operating in the area now flooded by the Tucuruí

Hydroelectric Dam: despite not having fulfilled its role in removing forest

from areas to be flooded, the concessionnaire was reportedly granted logging

rights to 93,000 ha in two nearby Amerindian reservations when commercially

valuable tree species proved less common than anticipated in the reservoir

area, according to the head of the firm involved (Pereira, 1982).

Future deforestation appears likely to

proceed at a rapid rate. Although

limited availability of fossil fuel, capital, and other resources should

eventually force a slowdown, this cannot be counted on to prevent loss of large

areas of forest. Even at rates slower

than those of the recent past, the forest could be reduced to remnants within a

short span of years. The deforestation

process is subject to control and influence at many points. Decisions affecting rates of clearing must be

based on understanding of the causes of deforestation. Such decisions are taken, either actively or

by default. They define areas to undergo

agricultural or other development, and reserves where such development will be

excluded. Making timely choices of this

kind depends on decision makers' conception of the likely course of

deforestation. Understanding the system

of forces driving the process is also essential for evaluating the probable

effectiveness of any changes contemplated.

4.3 POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The negative consequences of deforestation

(Fearnside nd-d) should give pause to planners intent on promoting forms of

development requiring large areas of cleared rainforest. Nevertheless, such plans continue to be

proposed and realized. Part of the problem

is a lack of awareness among decision-makers of the magnitude of the eventual

costs implied by these actions, but such lack of knowledge explains only a part

of the reluctance to take effective actions to contain and slow deforestation. At least as important is the distribution of

the costs and benefits, both in time and space.

Most of the costs of deforestation will be paid only in the future,

while the benefits are immediate. Many

of the costs are also distributed over society at large, while the benefits

accrue to a select few. In the many

cases where land is controlled by absentee investors there is even less reason

for negative consequences within the region to enter individual decisions. In other cases the costs are highly

concentrated, as when indigenous groups are deprived of their resource base,

while the perhaps meagre benefits of clearing are enjoyed by a constituency

that is both wider and more influential.

Brazil's national government has the task

of balancing the interests of different generations and interest groups. At the same time, the Amazon has long

suffered from exploitation as a colony whose products serve mainly to benefit

other parts of the globe, most recently and importantly the industrialized

regions of Brazil's Central‑South.

The unsustainable land uses resulting from this kind of

"endocolonialism," as Sioli (1980) calls it, require that

decision-making procedures guarantee the interests of the Amazon's residents

when conflicts arise with more influential regions of the country. Clear definitions of development objectives

are essential as a prerequisite for any planning (Fearnside, 1983c). I suggest that development alternatives be

evaluated on the basis of benefits to the residents of the Amazon region and

their descendants. Coherent policies

must include the maintenance of the human population below carrying capacity,

the implantation of agronomically and socially sustainable agroecosystems, and

limitations on total consumption and on the concentration of resources. The inclusion of future generations of local

residents in any considerations means that greater weight must be accorded the

delayed costs implied by such potential consequences of deforestation as

hydrological changes, degradation of agricultural resources, and sacrifice of

as yet untappable benefits from rainforest.

The folly of present trends toward rapid conversion of rainforest to

low-yielding and short-lived cattle pasture is evident, at least with respect

to the long-term interests of Amazonia's residents (Fearnside, 1979b, 1980c;

Goodland, 1980; Hecht, 1981).

4.4 CONCLUSIONS

1.)

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is proceeding rapidly. The future course of rainforest clearing

depends on a complex network of interacting factors. Forces such as a positive feedback

relationship between roadbuilding and land clearing can be expected to increase

deforestation, while factors such as the increasing importance of resident

population relative to the influx of immigrants should act to slow, but not stop,

the process. Rapid deforestation will

probably continue in the coming years.

2.)

Many government policies affect deforestation, including those related

to land tenure, reserve protection, investment incentives, and inflation.

3.)

Policies designed for the long‑term benefit of the Amazon's

residents and their descendants must include measures to slow and contain

deforestation. Such measures must be

based on sound understanding of the forces motivating deforestation, as well as

a clear definition of development goals.

The current pace of deforestation in the region suggests that, if they

are to be effective, any measures must be implemented quickly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank J.G. Gunn, D.H. Janzen, G.T.

Prance, J.M. Rankin, and G.M. Woodwell for their valuable comments on earlier

versions of the manuscript.

4.5 REFERENCES

Brazil, Ministério da

Agricultura, Instituto Brasileiro de Desenvolvimento Florestal (IBDF).

1983. Desenvolvimento Florestal no

Brasil, Proj. PNUD/FAO/BRA-82-008. Folha Informativa No. 5.

Brazil, Ministério da

Agricultura, Instituto Brasileiro de Desenvolvimento Florestal (IBDF).

1985. Alteração da cobertura vegetal

natural do Estado de Rondônia. Map scale: 1: 1,000,000. IBDF, Brasília.

Brazil, Ministério da

Agricultura, Instituto Nacional de Reforma Agrária (INCRA). 1980. Imposto Territorial Rural: Manual de

Orientação 1980. INCRA, Brasília. 10 pp.

Brazil, Presidência da

República, Secretaria de Planejamento, Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de

Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 1982. Anuário

Estatístico do Brasil ‑ 1981. Vol. 42. IBGE, Rio de Janeiro. 798 pp.

Bunker,

S.G. 1980. Forces of destruction in

Amazonia. Environment 22(7), 14-43.

Carneiro, C.M.R., Lorensi,

C.J., dos Santos Barbosa, M.P., de O. Almeida, S.A., de Queiroz, E.C., Daros,

L.L., Moreira, M.L., and Pereira. M.T. 1982.

Programa de Monitoramento da Cobertura Florestal do Brasil: Alteração

da Cobertura Vegetal Natural do Estado de Rondônia. Instituto Brasileiro de

Desenvolvimento Florestal (IBDF), Brasília. 68 pp.

Caufield, C. 1982. Brazil,

energy and the Amazon. New Scientist 96, 240-243.

Clark,

C.W. 1973. The economics of

overexploitation. Science 181, 630‑634.

Clark,

C.W. 1976. Mathematical Bioeconomics:

the Optimal Management of Renewable Resources. Wiley‑Interscience,

New York, 352 pp.

de Almeida, H. 1978. O desenvolvimento da Amazônia e a Política

de Incentivos Fiscais. Superintendência do Desenvolvimento da Amazônia

(SUDAM), Belém. 32 pp.

Denevan, W.M. 1982. Causes

of deforestation and forest and woodland degradation in tropical Latin America.

Report to the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), Congress of the United

States, Washington, D.C. 55 pp.

Egler, E.G. 1961. A Zona Bragantina do Estado do Pará. Revista

Brasileira de Geografia 23(3), 527-555.

Fearnside, P.M.

1979a. The development of the Amazon rain forest: priority problems for the

formulation of guidelines, Interciencia 4(6), 338‑343.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1979b. Cattle yield prediction for

the Transamazon Highway of Brazil, Interciencia 4(4), 220-225.

Fearnside, P.M. 1980a.

Desmatamento e roçagem de capoeira entre os colonos da Transamazônica e sua

relação à capacidade de suporte humano, \Ciência e Cultura\ 32(7) suplemento,

507 (abstract).

Fearnside,

P.M. 1980b. Land use allocation of the

Transamazon Highway colonists of Brazil and its relation to human carrying

capacity. Pages 114-138 In Barbira-Scazzocchio, F. (ed.) Land, People and

Planning in Contemporary Amazonia.

Centre of Latin American Studies Occasional Paper No. 3, Cambridge

University, Cambridge, U.K. 313 pp.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1980c. The effects of cattle

pasture on soil fertility in the Brazilian Amazon: consequences for beef

production sustainability, Tropical Ecology 21(1), 125-137.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1982. Deforestation in the

Brazilian Amazon: how fast is it occurring? Interciencia 7(2): 82-88.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1983a. Stochastic modeling and human

carrying capacity estimation: a tool for development planning in Amazonia.

Pages 279-295 In Moran, E.F. (ed.) The Dilemma of Amazonian Development,

Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 347 pp.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1983b. Land use trends in the Brazilian

Amazon Region as factors in accelerating deforestation, Environmental

Conservation 10(2), 141-148.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1983c. Development alternatives in

the Brazilian Amazon: an ecological evaluation, Interciencia 8(2),

65-78.

Fearnside, P.M. 1984a. A floresta vai acabar? Ciência Hoje

2(10), 42-52.

Fearnside, P.M.

1984b. Brazil's Amazon settlement schemes: conflicting objectives and human

carrying capacity, Habitat International 8(1), 45-61.

Fearnside,

P.M. nd‑a. Agriculture in

Amazonia. In Prance, G.T. and Lovejoy, T.E. (eds) The Tropical Rain Forest,

Pergamon Press, Oxford, U.K. (in press).

Fearnside,

P.M. nd‑b. Deforestation and

decision‑making in the development of Brazilian Amazonia. \Interciencia\

(forthcoming).

Fearnside,

P.M. nd-c. Land clearing behaviour in

small farmer settlement schemes in the Brazilian Amazon and its relation to

human carrying capacity. In Chadwick, A.C. and Sutton, S.L. (eds.) The

Tropical Rain Forest: Ecology and Resource Management, Supplementary Volume,

Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, Leeds, U.K. (in press).

Fearnside,

P.M. nd-d. Environmental Change and

deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. In Hemming, J., (ed.) Change in the

Amazon Basin: Man's Impact on Forests and Rivers. University of Manchester

Press, Manchester, U.K. (in press).

Fearnside,

P.M. and Rankin J.M. 1982. Jari and

Carajás: the uncertain future of large silvicultural plantations in the Amazon,

Interciencia 7(6), 326‑328.

Fearnside,

P.M. and Salati, E. nd. Desmatamento

explosivo em Rondônia. (Forthcoming).

Furley,

P.A. and Leite, L.L. nd. Land

development in the Brazilian Amazon with particular reference to Rondônia and

the Ouro Preto Colonization Project. In Hemming, J. (ed.) Change in the

Amazon Basin: the Frontier after a Decade of Colonization, University of

Manchester Press, Manchester, U.K. (in press).

Gligo,

N. 1980. The environmental dimension in

agricultural development in Latin America, Comisión Economica para América

Latina (CEPAL) Review December 1980, 129-135.

Goodland,

R.J.A. 1980. Environmental ranking of

Amazonian development projects in Brazil, Environmental Conservation

7(1), 9-26.

Hardin,

G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons, Science

162, 1243‑1248.

Hecht,

S.B. 1981. Deforestation in the Amazon

basin: practice, theory and soil resource effects, Studies in Third World

Societies 13, 61‑108.

Ianni, O. 1979. Colonização e Contra-Reforma Agrária na

Amazônia. Editora Vozes, Petrópolis, Rio de Janeiro. 137 pp.

Kleinpenning, J.M.G.

1975. The Integration and Colonisation of the Brazilian Portion of the Amazon

Basin. Katholieke Universiteit,

Geografisch Planologisch Instituut, Nijmegen, Holland. 177 pp.

Kleinpenning,

J.M.G. 1977. An evaluation of the

Brazilian policy for the integration of the Amazon region (1964-1974), Tijdschrift

voor Econ. en Sociale Geografie 68(5), 297‑311.

Léna, P. 1981. Dinâmica da estrutura agrária e o

aproveitamento dos lotes em um projeto de colonização de Rondônia. In Mueller,

C.C. (ed.) Expansão da Fronteira Agropecuária e Meio Ambiente na América

Latina. Departamento de Economia, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2

vols. (irregular pagination).

Mahar,

D.J. 1979. Frontier Development

Policy in Brazil: a Study of Amazonia. Praeger, New York. 182 pp.

Mesquita,

M.G.G.C. and Egler, E.G. 1979. Povoamento.

Pages 56-79 In Valverde, O. (ed.) A Organização do Espaço na Faixa da

Transamazônica, Vol. 1: Introdução, Sudeste Amazônico, Rondônia e Regiões

Vizinhas. Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE),

Rio de Janeiro. 258 pp.

Moran,

E.F. 1980. Developing the Amazon.

Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. 292 pp.

Myers,

N. 1980. Conversion of Tropical Moist

Forests, National Academy of Sciences Press, Washington, D.C. 205 pp.

Myers,

N. 1982. Depletion of tropical moist

forests: a comparative review of rates and causes in the three main regions, Acta

Amazonica 12(4), 745-758.

Pereira, F. 1982. "Tucuruí: já retirados 15% da

madeira." Gazeta Mercantil (Brasília), 6 October 1982, p. 11.

Plumwood,

V. and Routley, R. 1982. World

rainforest destruction‑‑ the social factors, The Ecologist

11(6), 4-22.

Saunders,

J. 1974. The population of the Brazilian

Amazon. Pages 160‑180 In Wagley, C. (ed.) Man in the Amazon,

University Presses of Florida, Gainesville, Florida. 329 pp.

Sawyer,

D. 1982. Frontier expansion and

retraction in Brazil. Paper presented at the Seminar on Frontier Expansion in

Amazonia. University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, February 8‑11,

1982. (forthcoming).

Sioli,

H. 1973. Recent human activities in the

Brazilian Amazon Region and their ecological effects. Pages 321-334 In Meggers,

B.J., Ayensu, E.S. and Duckworth, W.D. (eds.) The Tropical Forest Ecosystem

in Africa and South America: a Comparative Review. Smithsonian Institution

Press, Washington, D.C. 350 pp.

Sioli,

H. 1980. Foreseeable consequences of

actual development schemes and alternative ideas. Pages 257-268 In Barbira‑Scazzocchio,

F. (ed.) Land, People and Planning in Contemporary Amazonia. Centre of Latin

American Studies Occasional Paper No. 3, Cambridge University, Cambridge, U.K.,

313 pp.

Smith,

N.J.H. 1982. Rainforest Corridors:

the Transamazon Colonization Scheme. University of California Press,

Berkeley, California. 248 pp.

Tambs,

L.A. 1974. Geopolitics of the Amazon.

Pages 45-87 In Wagley, C. (ed.) Man in the Amazon. University Presses of

Florida, Gainesville, Florida. 329 pp.

ardin, A.T., Lee, D.C.L.,

Santos, R.J.R., de Assis, O.R., dos Santos Barbosa, M.P., de Lourdes Moreira,

M., Pereira, M.T., Silva, D., and dos Santos Filho, C.P. 1980. Sub projeto Desmatamento, Convênio

IBDF/CNPq‑INPE 1979. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais-INPE,

Relatorio INPE-1649-RPE/103, São Paulo, São José dos Campos, 44 pp.

Zockun, M.H.G.P.

1980. A expansão da Soja no Brasil:

Alguns Aspectos da Produção. Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas da

Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 243 pp.

Table

1. Proximal causes of deforestation

______________________________________________________________________

PRINCIPAL LINK TO RELATIVE IMPORTANCE BY SIZE OF HOLDING

PRESENT DEFOREST- ‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑

MOTIVES ATION Small Large

Properties Properties

______________________________________________________________________

1.)

Land Clearing Important in Important in areas

specula-

establishes squatter

areas held by grileiros

tion.

proprietary and for

tenta- (land grabbers) as

claims, raises tively docum- well as in legally

resale value ented colonists documented areas

of land. in official (difficult to defend

settlement from squatters).

areas.

2.)

Tax Businesses Not a factor. Important in projects

incen‑ can avoid approved by the

tives.

paying taxes Superintendency for

owed on enter- the Development of

prises else- Amazonia (SUDAM)

where in Brazil (mostly in Pará)

if money is in- or by the

vested in Superintendency for

Amazonian the Manaus Free

ranches (Bunker, Trade Zone (SUFRAMA)

1980; de Almeida,

(in Amazonas).@7oa@8o

1978; Fearnside,

1979a; Mahar, l979).

Tax

Higher taxes Not

important. May become important.

penalties.

on "unused"

(i.e. un-

cleared) land

(Brazil,

Ministério da

Agricultura,

INCRA, 1980).

3.)

Negative Financing of Not a factor. Important.

As with

interest

government-

tax incentives, most

loans and

approved

important in southern

other

ranching pro-

Pará.

subsidies.

jects at nominal

interest rates

lower than

inflation.

4.)

"Chrono- Government- Not a factor. Important in SUDAM and

grams" for approved SUFRAMA project areas,

incenti-

ranching pro-

but many ranches

vated

jects must

receive subsidies

projects.

adhere to a

without full

schedule for compliance.

clearing to

qualify for

continued in-

centives.

5.)

Special Cacao, coffee, Important in Important for rela-

crop

rubber, black official tively few large

loans.

pepper, sugar colonization holdings, although

cane, and areas. medium-sized holdings

annual crops (500-2000 ha) benefit

are financed in in Rondônia.

some areas.

These crops

would not be

attractive with-

out the favorable

loan terms.

6.)

Export‑ Beef, and to Important among Important, although

able

a lesser small farmers often larger holdings

product-

extent cacao, who depend are integrated into

tion.

upland rice, on cash crop more diversified

and other sales for investment portfolios.

crops, are year-to-year In the case of oper‑

sold in other survival. ations largely

regions or Speculative motivated by subsidies

countries. benefits come and speculative oppor‑

as a windfall tunities, sale of

for these, production, even if

although a meagre, adds to the

significant profit from

clearing.

number of lots

are owned by

non‑resident

speculators for

whom agricul-

tural produc-

tion is a minor

consideration.

7.)

Subsis- Relatively Minor, espec- Not significant.

tence

minor. ially in gover-

produc- ment coloniza-

tion. tion areas,

where most

clearing is

for cash crop

planting.

______________________________________________________________________

New

incentives for cattle ranches from the Superintendency for

Development

of the Amazon (SUDAM) were suspended in 1979 for areas

classified

as "high forest," but new projects continue to be

approved

for "transition forest" areas, and the hundreds of pre-

viously

approved projects in the high forest areas continue to

receive

incentives for clearing, most of which has yet to be done.

Table 2. Underlying causes of

deforestation

___________________________________________________________________

Cause Link to Deforestation

___________________________________________________________________

1.)

Inflation. a.) Speculation in

real property, especially

pasture land.

b.) Increased

attractiveness of low-interest

bank loans for

clearing.

2.)

Population a.) Increased demand

for subsistence pro-

growth. duction (minor factor).

b.) Increased capacity

to clear and plant,

both for

subsistence and cash crops.

c.) Increased political

pressure for road

building (feeds

back to item 4).

.)

Mechanization of a.) Immigration of

landless laborers (in-

agriculture in creasing felling both as squatters

and

southern Brazil as workers on other properties).

and absorption b.) Immigration of smallholders to

purchase

of small holdings land (both augment item 2).

by large estates

in the south and

northeast.

4.)

Road building and a.) Immigration to

Amazonia (feeds back to

improvement. item 2).

b.) Increased clearing by persons already

present.

5.)

Low land prices. a.) Extensive land

uses (e.g. pasture).

b.) Little concern for

sustainability of

production.

c.) Attraction of

smallholders to immigrate

to Amazonia.

d.) Little motivation

for landholders to

defend uncleared

areas from squatters.

e.) Greater potential speculative gains.

.)

National a.) Tendency of

Amazonian interior residents

politics. to support incumbent governments

provides

incentive to

increase political

representation of these

areas by creating

new territories and

states, justified by

population growth

achieved through

colonization

programs and highway

construction.

b.) During specific

periods of social tension

in non-Amazonian

portions of Brazil, as

in 1970, road

building and colonization

programs in Amazonia have

been seen as

ways to alleviate

pressure for land reform

(e.g. Ianni,

1979). The effect of

publicity

surrounding the programs appears

to be more

important than actual

population flow.

7.)

International Government leaders

frequently justify road

geopolitics. building and colonization near

international

borders as protecting

the country from

invasion (Kleinpenning,

1975, 1977;

Tambs, 1974). These

claims can be effective in

rationalizing

government programs desired

for other reasons

(Fearnside, 1984b;

Kleinpenning, 1977:

310).

8.)

Concentration of Displaces population

when squatters' claims

land tenure in or small holdings are taken by large

Amazonia. ranches. Displaced persons move to clear

new areas.

9.)

Fear of forest. Deep-seated

psychological aversion to forest

and fear of dangerous

animals impedes forested

land uses.

This fear is especially powerful

among recent arrivals

from other regions

(e.g. Moran,

1980: 99).

10.)

Status from Longstanding Iberian

tradition of according

cattle. higher social status to ranchers than farmers

leads to preference for

pasture independent of

expected profit

(Denevan, 1982; Smith, 1982:

84).

11.)

Availability of Heavy discounting of

expected future costs

alternative and returns for investments in the

Amazon,

investments leading to little concern for sustain-

elsewhere. ability of production systems (see

Clark

1973, 1976).

12.)

Distribution of Increases relative

economic attractiveness

environmental to individual investors of land uses

costs of requiring large deforested areas, as

deforestation compared to intensive use of small

clearings

over society or sustained management of standing

forest

at large. (see Hardin, 1968).

13.)

Unsustainable Clearing more area to

substitute for no‑

land use choices longer-productive land.

for cleared

areas.

14.)

Low labor a.) Small population

can clear and exploit

requirement of a large area.

predominant land b.) Little contribution to solving problems

use (e.g. of unemployment, underemployment,

and

pasture). landlessness, which encourage

further

deforestation.

15.)

Low agricultural a.) Increased area

needed to supply subsis‑

yields. tence demand (relatively minor).

b.) Money from

government subsidies spent

on unproductive

ranches and other

projects fuels

inflation by increasing

purchasing power of

beneficiaries, with-

out contributing

corresponding amounts of

production to the

economy (feeds back to

item 1).

Table

3. Expected additional motives for

future deforestation.

___________________________________________________________________

Motive Reason expected

___________________________________________________________________

1.)

Timber export. Expected to increase

with coming end to

Southeast Asian

rainforests now supplying

world markets

(Fearnside and Rankin l982).

2.)

Charcoal Expected to increase

for steel production

production. for the Grande Carajás Project, in

south-

eastern Pará. Both native forest harvest

and plantations are

planned.

3.)

Support of mineral Expected to accompany

developments at

development Carajás, Trombetas, Serra Pelada, and

sites. elsewhere.

4.)

Hydroelectric Planned projects at

Balbina (Rio Uatumã)

projects. Samuel (Rio Jamari) and Itapunara

(Rio Jari)

would total 4445 km2

of reservoir area

(Goodland, 1980), plus additional unknown

areas from 2 dams on

the Rio Xingú and

up to 4 additional dams

on the Rio Tocantins

(Goodland,

1980)@7oa@8o. Existing dams in the

region at Curuá-Una (Rio

Curuá-Una)

and Paredão, also known as Coary Nunes

(Rio

Araguari), and Tucuruí (Rio Tocantins)

total 2539 km2. Some new area will be cleared

by persons displaced by the

dams, as well as

by expected support

communities. Fluctuations

in released water

volume, as at Balbina, will

also kill substantial

forest areas downstream

of the dams. Forest loss from hydroelectric

projects, however, is

small when compared

with losses to ranching

or other activities.

‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑‑

Ultimate

goals for the Rio Tocantins and its tributaries reportedly call for

construction of 8 large dams (including Tucuruí) plus 19 smaller ones, while

the Rio Xingú would eventually have 9-10 large dams (Caufield l982).

FIGURE

LEGENDS

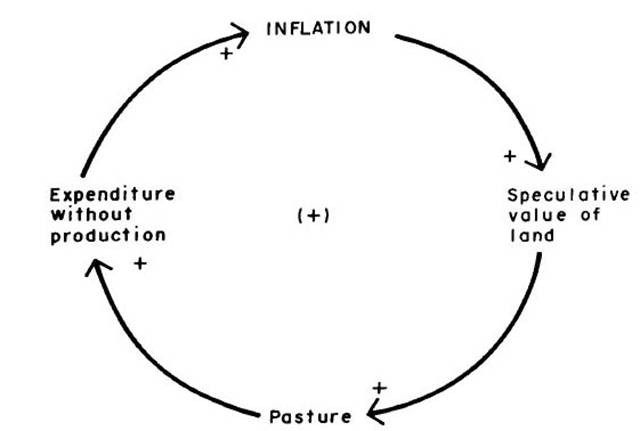

Fig. 4.1.Brazil's "Legal Amazonia."

Fig. 4.2.Growth of population and deforested area

in the state of Rondônia. Deforested

area is growing even more rapidly than population in this focus of rainforest

clearing in Amazonia. Ten‑year interval populations are from census data

compiled by the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE)

(Saunders, 1974; Brazil, Presidência da República, IBGE, 1982: 74); 1976

intercensal estimate is by IBGE (Mesquita and Egler, 1979: 73). Deforestation estimates for 1975 and 1978 are

from Tardin et al. (1980); 1980 estimate is from Brazil, Ministério da

Agricultura IBDF (1983).

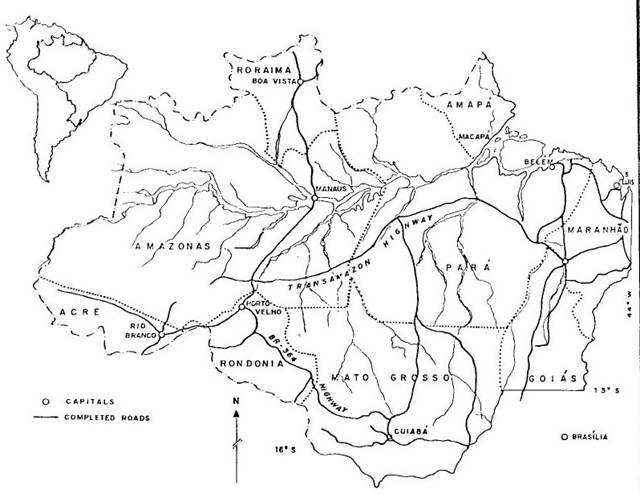

Fig. 4.3.Causal loop diagram of the relationship

between roadbuilding and deforestation. Signs

by arrow heads indicate the direction of change that would result from an

increase in the quantity at the tail of the arrow. Roads and population form a positive feedback

loop. Roads also increase land values,

leading the original colonists to sell their land top newcomers who clear more

rapidly. Improved transport for

agricultural production makes farming more profitable, leading colonists to

clear and plant larger areas.

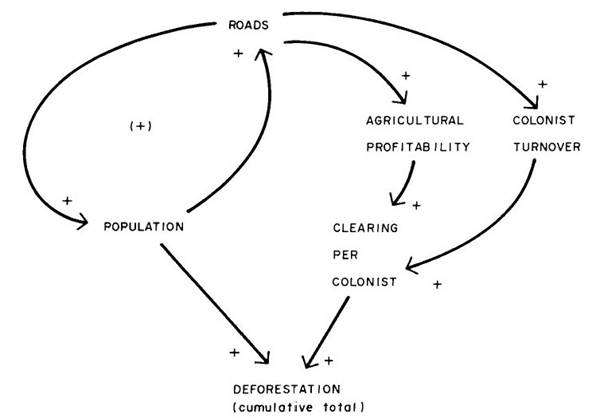

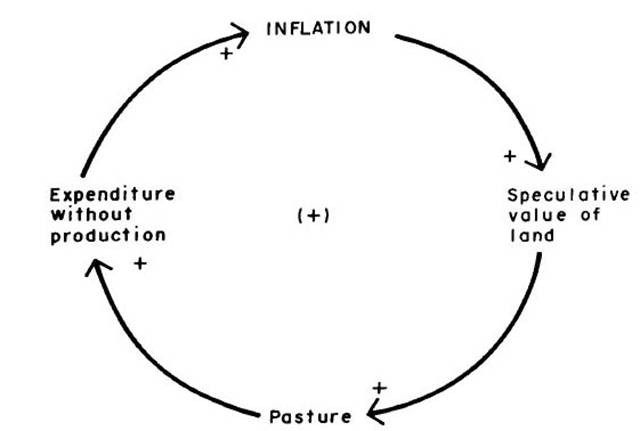

Fig. 4.4.Causal loop diagram of the relationship

of inflation to deforestation for cattle pasture. High inflation leads to land speculation as a

means of preserving the value of money.

Pasture is planted to secure these investments against squatters or

other claimants. The low production of

beef from pastures on these soils means that the money invested in ranching is

increasing the demand for products in the marketplace without contributing

anything that can be bought. The

increase of demand over supply raises prices, contributing to still higher

inflation.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4