The text that follows is a PREPRINT.

Please cite

as:

Fearnside, P.M.

1989. Brazil's Balbina Dam: Environment

versus the legacy of the pharaohs in Amazonia. Environmental Management

13(4): 401-423.

ISSN: 0364-152X

Copyright:

Springer.

The original publication is available at www.springerlink.com

BRAZIL'S BALBINA DAM: ENVIRONMENT VERSUS THE LEGACY OF THE PHARAOHS IN

AMAZONIA

Philip M. Fearnside

Department of Ecology

National Institute for Research

in the Amazon (INPA)

C.P. 478

69.011 Manaus – Amazonas

BRAZIL

30 September 1988

BRAZIL'S BALBINA DAM: ENVIRONMENT VERSUS THE LEGACY OF

THE PHARAOHS IN AMAZONIA

PHILIP M. FEARNSIDE* National Institute for Research in

the Amazon (INPA), Manaus, Brazil

Summary--The Balbina Dam in Brazil's state of Amazonas will

flood a 2360 km2 of tropical forest to generate an average of only

112.2 MW. The flat topography and small

size of the drainage basin make output small.

Vegetation has been left to decompose in the reservoir, which can be

expected to result in acid, anoxic water that will corrode the turbines. The shallow reservoir will contain 1500

islands and innumerable stagnant bays where the water's residence time will be

even longer than the average time of nearly one year. Balbina was built to supply electricity to

Manaus, a city that has grown so much while the dam was under construction that

other alternatives are already needed.

Government subsidies explain the explosive growth. Unified tariffs for electricity encourage

industrial development in inappropriate locations. Alternative power sources for Manaus include

transmission from more distant dams or from recently discovered oil and natural

gas deposits. Among Balbina's impacts

are loss of potential use of the forest and dislocation of about one‑third

of the surviving members of a much‑persecuted Amerindian tribe: the

Waimiri-Atroari. The dam was closed on 1

October 1987; power generation is scheduled for October 1988 but may be

delayed. The example of Balbina points

to important ways that the decision‑making process could be improved in

Brazil and in the international funding agencies that have directly and

indirectly contributed to the project.

1. INTRODUCTION

(a) The Balbina Dam .

Balbina is a

hydroelectric dam built to supply power to the city of Manaus, in the center of

Brazil's Amazonian region. The dam is

located in an area with flat topography, creating a huge reservoir and

generating very little power. Part of an

Amerindian reservation will be flooded.

The tropical forest was not cleared in the submergence area, leaving the

skeletons of the dead trees standing in the shallow water. The vegetation is expected to decompose in

stagnant backwaters of the reservoir, which is a maze of channels and islands

over 150 km long and 85 km wide (Figure 1).

The dam is on a small river, and water will remain standing in the

reservoir for an average of almost a full year.

The acid, anoxic water is expected to corrode the turbines as has

occurred at other dams in the region where conditions are more promising than

at Balbina. The cost of generating power

at Balbina will be several times higher than at more favorable sites. Other options for power supply exist for the

city of Manaus, and the small capacity of Balbina means that they would have to

be tapped whether or not Balbina were built.

The initial

decision to build Balbina is difficult to justify in technical terms. More disturbing is the unstoppable force that

the project has gathered as it became 'irreversible' and continued to

completion. Dubbed the 'notorious

Balbina Dam' in the World Bank appraisal report on the request for its funding

(see: Environmental Policy Institute, 1987), it has succeeded in circumventing

environmental hurdles both at the national and state levels in Brazil and, to a

certain extent, within the World Bank as well.

The World Bank refused to finance construction of Balbina on

environmental and economic grounds. The

Bank later approved a US$500 million 'sector loan' to supply imported equipment

for the entire electrical power sector of Brazil. Although individual projects within the

sector are not subject to environmental review, World Bank officials say that

the turbines and other equipment for Balbina had already been bought before the

loan was granted in mid-1986 so that no Bank money was used directly for this

purpose (Maritta Koch-Weser, personal communication, 1988). The turbines arrived in Manaus after that

time, but confirmation is lacking as to when payment was made. At the least, the injection of funds into the

sector frees Brazilian government monies that would otherwise have been spent

on higher priority projects elsewhere.

It is difficult to assess how much this indirect effect has speeded

construction at Balbina. Balbina has

long been a marginal project in Brazil's overstretched federal budget: in June

1985 Balbina was to have been suspended because of budget cuts following an

agreement with the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) on Brazil's foreign

debt; only urgent appeals to President Sarney by the governor and other state

representatives averted the cutoff O Jornal do Comércio, 11 June 1985; A

Notícia, 12 June 1985). Limited

funds have delayed the project several times ‑‑ plans called for

beginning construction in 1979 and power generation for 1983, but work did not

begin until 1981. On 16 April 1988, with

the filling process already underway, it was announced that the beginning of

power generation might be delayed beyond the official startup date of October 1988

because US$85 million of the budget had not been liberated and vital equipment

remained undelivered, including the electrical panels, filters, cables, and the

refrigeration system for the turbines.

No information is available concerning whether any of the remaining

equipment had to be imported. The dam

illustrates a number of common patterns in the development planning process

throughout Amazonia that result in little consideration being given to the

environment.

Balbina is among

the projects that are known in Brazil as 'pharaonic works' e.g., Veja,

20 May 1987). Like the pyramids of

ancient Egypt, these massive public works demand the effort of an entire

society to complete but bring no economic returns. Even if the structures are simply built and

abandoned they serve the short‑term interests of all concerned ‑‑

from firms that receive construction contracts to politicians wanting the

employment and commerce that the projects provide to their districts during the

construction phase.

On 1 October 1987

The Balbina Hydroelectric Dam began its first stage of filling on the Uatum~

River, 146 km northeast of Manaus in Brazil's state of Amazonas. The dam is a focus of controversy because a

large area (2360 km2) will be flooded

to produce a meager amount of power (112.2 MW average output from 250 MW

installed capacity). With almost 800 km2 of the reservoir less than four meters deep the decomposing tropical

forest vegetation is expected to make the water very acid and corrosive to the

turbines for several years, as well as favoring the growth of aquatic

plants. The dam was decreed without

environmental impact studies or public discussion. Public and scientific debate on the

undertaking has been hampered by heavy secrecy and restrictions on information

flow between research groups conducting environmental studies on the dam during

the construction phase. An intense

advertizing campaign by ELETRONORTE (the government power monopoly in northern

Brazil) implies that the dam will benefit the environment, a view not shared by

any of the researchers studying the project.

The public relations campaign included radio advertizements broadcast in

Manaus at 15 minute intervals in August 1987; in one of these the voice of

Curupira ‑‑ the spirit of the forest ‑‑ assured

listeners that he would not allow Balbina to exist were the dam not good for a

long list of familiar species of fish and wildlife. In one television commercial a cavewoman is

clubbed over the head with a large bone in a representation of how without Balbina

Manaus would revert to neolithic times.

Many of the advertizements on all media carried the explicit statement

that 'whoever is against Balbina is against you' e.g. Brazil,

ELETRONORTE, 1987a).

(b) The 2010 Plan

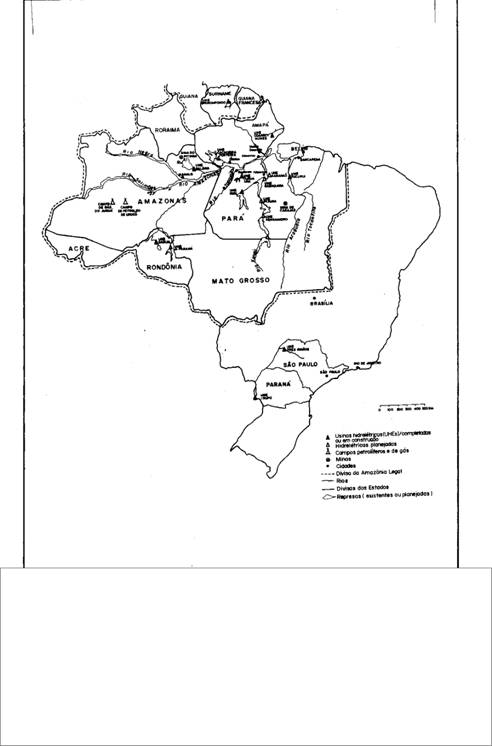

Reservoirs for hydrolectric

power generation are claiming a greater and greater share of Amazonian

forest. The potential for expansion of

impacts from this sector is large: ELETROBR'S (the Brazilian government's power

monopoly) has published a '2010 plan' outlining the possible construction of 68

dams by the year 2010 (Brazil, ELETROBR'S, 1986a; see also CIMI, 1986), with

the total rising to as many as 80 dams within a few decades (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE, 1985a: 25-26). The 80 dams

would flood roughly 2% of Brazil's Legal Amazonia ‑‑ a percentage

that, while seemingly small, would provoke forest disturbance in much wider

areas. Aquatic habitats would, of

course, be drastically altered. Most of

the sites that are favorable for hydroelectric development are located along the

middle and upper reaches of the tributaries that begin in Brazil's central

plateau and flow north to meet the Amazon River ‑‑ the Xingu,

Tocantins, Araguaia, Tapajós, and others (Figure 2). This region has one of the highest

concentrations of indigenous peoples.

THE DECISION TO

BUILD BALBINA

The question of why

Balbina was initiated and why it was continued after its folly became clear is

relevant to the problems of planning large scale developments throughout the

region. A number of theories exist to

explain Balbina which merit examination.

The decision was

taken at the time when global oil prices were at their highest peak, and when

the technology for long-distance power transmission was not so well developed

as it is today. These facts, together with

the gross underestimates of the growth of population and power demand in

Manaus, are the official explanation for the decision, which ELETRONORTE

concedes would have been unjustifiable had the events of the last decade been

known in advance (Lopes, 1986). However,

even with the information available at the time (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976), Balbina is questionable as a technical

decision.

When the viability

study was done in 1975‑1976, restrictions on public communication meant

that Brazil's military government had little reason to worry about questioning

of its decisions. ELETRONORTE employees

have unofficially stated that they received the order to build the dam directly

from the planalto (Brazil's presidential office) ‑‑ it was

not a proposal developed on technical grounds and passed up the hierarchy for

approval. The government was anxious to

have something to give to the state of Amazonas; the nearest alternative

hydroelectric site with substantially better potential (Cachoeira Porteira) is

in the adjoining state of Pará.

The military

political party (PDS) was in power at the time both at the national level and

in the state of Amazonas, and stood to gain support in the 1982 elections from

the ruling party's image as a route to central government largesse. Balbina was presented to the public as an

example of the governor's ability to extract benefits from Brasília. In the 1982 election, however, the PDS lost

the governorship of Amazonas; at that juncture the new majority party (the

PMDB) could have cast off Balbina as a folly of the previous government. After some initial hesitation, however,

Balbina was endorsed by the new administration and carried forward as a

salvation of the state. The initial

hesitation in endorsing Balbina eliminates the popular theory that the new

governor (Gilberto Mestrinho) supported the project for sentimental reasons

stemming from the fact that, by coincidence, his mother's name is Balbina (she

is honored by the state government's Balbina Mestrinho maternity clinics in

Manaus).

Another popular

theory is that Balbina was built in order to facilitate the extraction of

minerals from the area, particularly cassiterite (tin) ore (Garcia, 1985). The Pitinga mine, located in the upper

reaches of the Balbina catchment and in the adjoining Alalaú catchment, is

credited with being the world's largest high‑grade tin deposit. Some tin occurrences have been identified in

the submergence area, but ELETRONORTE insists that they are not economically

exploitable (Col. Willy Antônio Pereira, personal communication, 1987; Junk and

de Mello, 1987). A survey of the Pitinga

River portion of the Balbina submergence area indicated some occurrences but

not vast deposits (Viega Junior et al., 1983: Vol. I-b, pp. 458-462,

Vol. II Anexo IIIc). The price of tin,

however, is at one of its historic lows: currently US$5.50/kg, compared to a

former price of US$17.60/kg Newsweek, 14 July 1986). No information is available on how much the

price would have to rebound before the Balbina deposits became economically

attractive. The presence of the

reservoir would also alter the economic equation, since the ore could be

scooped or sucked up from the bottom from dredges mounted on barges. This possibility has even been raised by the

Manaus representative of the National Department of Mineral Production Amazonas

em Tempo, 6 September 1987).

Cassiterite in Amazonia is often mined from barges floating in

artificial ponds built for the purpose.

Dredges can operate to a depth of 30 m, and so would have access to the

entire reservoir (which will have a maximum depth of 21 m). Since the mineral occurrences are in the

upper reaches of the submergence area, they would be in the shallowest portion

most easily dredged from barges (depths less than 6 m). Mining companies have registered prospecting

claims to a large part of the submergence area according to a map made by

Brazil's National Department of Mineral Production (map reproduced in:

Melchiades Filho, 1987). Property

ownership in Brazil does not include rights to underground mineral deposits;

the deposits belong to the government until ceded to private parties who

register prospecting claims.

The submergence

area also contains gold (Junk and de Mello, 1987) ‑‑ another

mineral often mined from barges.

Although ELETRONORTE says the deposits are not economically attractive,

as late as 1983 the director of the National Department of Mineral Production

(DNPM) in Manaus urged the state governor to have gold mining begin immediately

because Balbina would soon flood the deposit O Jornal do Comércio, 23

June 1983). ELETRONORTE officials at

Balbina point out that if the gold in the area were attractive it would already

be being exploited by the flocks of freelance prospectors that have been

attracted to gold-rich areas elsewhere in Amazonia. Their absence confirms the low concentrations

indicated by surveys commissioned by ELETRONORTE, which found an average of

0.13 g of gold per cubic meter of ore (Col. Willy Antônio Pereira, personal

communication, 1987). A survey

commissioned by the National Department of Mineral Production in the Pitinga

River portion of the submergence area indicated several occurrences, but no

large deposits (Viega Junior et al., 1979: Vol. II-b, pp. 467-469, Vol.

II Anexo III-c). As with cassiterite,

the possibility of using barges and the fluctuations in mineral prices could

change the economic attractiveness of the deposits in the future.

ELETRONORTE

officials deny any connection of Balbina with mining, rightly pointing out the

damage that sedimentation caused by any such activity would bring to power

generation at the dam. Despite these

events involving the Balbina area, any causal link between mining interests and

the decision to build Balbina remains pure speculation.

Another theory for

the motivation behind Balbina involves the indemnization that landowners would

receive. ELETRONORTE maps show that,

except for the land taken from the Waimiri-Atroari tribe, almost all of the

project area is privately owned (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, nd). The payment of compensation was still under

negotiation during the final months before the reservoir commenced

filling. Although it is logical that

those who claim property rights to the land are trying to get as much financial

reward as possible, it is unlikely that this interest group influenced the

overall decisions regarding the project.

Due to delays and

other reasons, the cost of the dam has increased from an initial estimate of

US$383 million (Brazil, ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: A-24) to somewhere

between US$730 million Veja, 20 May 1987) and US$744 million A

Crítica, 11 June 1985) ‑‑ exclusive of the transmission

line. These increases have undoubtedly

heightened even more the interest of those that supply goods and services to

the construction project. The commercial

sector of Manaus has been particularly strong in its efforts to prevent funds

for Balbina from being cut A Crítica, 14 June 1985). While many Manaus residents and politicians

defend Balbina with great vehemence, such support would probably evaporate

quickly were the local taxpayers required to pay the project's financial

cost. At present Manaus is receiving

Balbina as a gift from taxpayers elsewhere ‑‑ both in the rest of

Brazil and, indirectly, in the foreign countries that have funded the World

Bank's Brazilian power sector loan.

3. THE

TECHNOLOGICAL FOLLY

Severe as Balbina's

impacts are, the magnitude of the environmental and financial disaster at

Balbina lies in the meager benefits that the project will produce. Balbina's nominal capacity is 250 megawatts

(MW): the sum of five generators of 50 MW capacity each. The amount of power that the dam will

actually produce, however, is much less than this. At full capacity, each generator uses 267 m3/second of water (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b), or 1335 m3/second for all five generators.

The annual average flow of the Uatum~ River at the dam site was

estimated to be only 657 m3/second (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: A-21), or slightly more than that needed for

two turbines (on average). Since 13% of

the annual total discharge is expected to be passed over the spillway without

generating power, an average output of 112.2 MW is expected (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: B-51).

Of this, 64 MW represents 'firm power' at a water level depletion of 4.4

m, the maximum for which the turbines were designed (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE‑RIO, 1976: B-47).

An assumed 2.5% loss in transmission reduces the firm power delivered to

Manaus to only 62.4 MW (Brazil, ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: B-49). Some ELETRONORTE calculations assume a 5%

transmission loss (Brazil, ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: B-47), which

would imply a firm power in Manaus of only 60.8 MW. Although all dams generate less than their

nominal capacity, at 26% Balbina's firm output at the damsite is less than

normal.

Balbina's 250 MW

nominal capacity is itself miniscule for a reservoir of this size ‑‑

about as large as the 2430 kmD2U Tucuru' reservoir that will support a nominal

capacity of 8000 MW. Balbina sacrifices

31 times more forest per megawatt of generating capacity installed than does

Tucuru'. Low output is a logical

consequence of the area's flat terrain and of the Uatum~ River's low

streamflow. A severely limited supply of

water is an inevitable result of Balbina's small drainage basin (18,862 km2: Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b).

The drainage basin is only eight times larger than the reservoir itself ‑‑

a highly unusual situation in hydroelectric development.

The amount of water

flowing past the damsite is crucial to Balbina's ability to deliver the power

its designers hope to obtain. The

streamflow sometimes falls to almost nothing: in March 1983 the flow at Balbina

reached a low of 4.72 m3/second according to

ELETRONORTE's measurements at the dam site (Posto 08). This is a quantity appropriate for a small

brook rather than a hydroelectric project ‑‑ engineers at the

construction site were able to ford the river in Volkswagens. The 'minimum registered streamflow' indicated

in ELETRONORTE's publicly-distributed pamphlet describing the project does not

reflect this dramatic water shortage: a value of 68.9 m3/second is given in the October 1985 version of the pamphlet,

subsequently revised to 19.7 m3/second in the

February 1987 version (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1985b, 1987b). ELETRONORTE officials explain the discrepancy

by saying that the 'minimum' refers to a monthly mean value rather than to the

flow on any given day. It is worth

noting that the monthly mean streamflow in February 1983 was 17.51 m3/second.

Each turbine will

require 267 m3/second of water to generate its full

50 MW of electricity (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b). The turbines can operate with less water, but

produce less power. Impressive as the contrast

between water requirements and the minimum streamflows is (whether expressed as

a daily measurement or as a monthly mean), the stored water in the reservoir

will allow the dam's operators to cushion the powerplant against brief periods

of low streamflow. The annual average

streamflow, however, is not a limitation that can be circumvented by judicious

management of the reservoir. Even a

rough calculation based on the drainage area and the rainfall indicates that

the annual average streamflow will be small: the average annual precipitation

registered at Balbina of 2229 mm (Januário, 1986: 15) falling over the 18,862

km2 basin would produce a volume of water which, allowing

for 50% return to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration (Leopoldo et al.,

1982; Villa Nova et al., 1976) would yield an average streamflow of 666

m3/second. This

does not include evaporation from the water standing in the lake, which would

be substantial in a shallow reservoir covered with macrophytes. ELETRONORTE's viability study had also

estimated a low annual average streamflow: 657 m3/second (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: A-21).

Much of the

reservoir will be extremely shallow because the terrain at Balbina is quite

flat. The reservoir's 2360 km2 area at the 50 m level falls to 1580 km2 at the 46 m level, meaning that 780 km2 (33%) will be less than four meters deep. Average depth when full will be 7.4 m

(Brazil, ELETROBR'S, 1986b: 6.12). The

large shallow areas can be expected to support rooted aquatic vegetation,

adding to the problem of floating weeds that could affect the entire

reservoir. The combination of large

surface area per volume of water in a shallow reservoir and high biomass of

aquatic vegetation will lead to heavy loss of the stored water to evaporation

and transpiration. A herd of manatees is

being bred in an effort promoted by ELETRONORTE as an antidote to weeds ‑‑

for example by means of a comic book distributed in Manaus in which a parrot

explains the 'marvelous trip of the light to your house' (Brazil, ELETRONORTE,

nd (1987)). The staff at the National

Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) reponsible for the program view it

strictly as a research effort rather than as a means of controlling the weeds

since the manatees breed very slowly (Vera da Silva, personal communication,

1988). Manatees have a long gestation

period (Best, 1982), which, together with inhibited fertility during lactation,

restricts reproduction to one calf per female every three years (Best, 1984:

376 and Vera da Silva, personal communication, 1988). In the meantime, ELETRONORTE has begun

pulling out some of the weeds by hand and removing them from the area using

outboard motorboats and trucks ‑‑ a method that is unlikely to be

financially sustainable.

The Balbina

reservoir will be a labyrinth of canals among the approximately 1500 islands

and 60 tributary streams. The residence

time in some of these backwaters will be many times more than the already

extremely long average of 11.7 months (Brazil, ELETROBRÁS, 1986b: 6.12). Water in Tucuru', by contrast, has an average

residence of 1.8 months, or 6.4 times less.

Some parts of the Balbina reservoir may only turn over once in several

years. In addition to Balbina's

reticulate arrangement of interconnecting backwaters (Figure 1c), which

resembles a cross‑section of a human lung, the residence time at the

bottom of the reservoir (where the decomposing leaves are concentrated) would

be greater than the reservoir's average because of an expected thermal

stratification (Fisch, 1986). The water

entering the reservoir flows toward the dam in the surface layers (Branco,

1986), although some mixing will occur near the dam since the water removed

from the reservoir will be taken from the bottom where the intakes for the

turbines are located. The slow turnover

means that the decomposing vegetation will produce acids that cause corrosion

of the turbines. In Tucuruí, despite the

relatively rapid average turnover in the reservoir dominated by flow through

the main channel, one side arm that communicates with the main reservoir

through a narrow neck is fed by streams that are so small that in dry years

water entry corresponds to a turnover time on the order of 50 years. Prior to closing the dam, ELETRONORTE

bulldozed the vegetation in this bay, known as the Lago do Caraip', in order to

render the area as sterile as possible, thereby minimizing eutrophication (Col.

Willy Antônio Pereira, personal communication, 1987; see Brazil, INPA, 1983:

32-34). Special treatment was undoubtedly

also motivated by the bay's proximity to populated areas near the dam. Even with the bulldozing, the bay was quickly

covered by mats of floating macrophytes (Cardenas, 1986a: 9, 17).

Acid

water caused by decomposing vegetation can make maintenance costly. Tucuruí has already had repairs to its

turbines, costing an undisclosed amount.

At the Curuá-Una Reservoir near Santarém, Pará, power generation had to

be halted temporarily in 1982 (only five years after the dam began to produce

electricity) to allow repairs to the corroded turbines at a cost of US$1.1

million (Brazil, ELETROBRÁS/CEPEL, 1983: 34).

The cumulative cost of maintenance in the first six years totaled US$2

million, or US$16,600 per installed megawatt per year ‑‑ 70 times

the cost per megawatt for a comparable dam in the semi‑arid northeastern

part of Brazil (Brazil, ELETROBRÁS/CEPEL, 1983: 44). The report is richly illustrated with

photographs of the deeply-pitted turbines at Curuá-Una. Lost generating time is not included in the costs

of maintenance reported. The average

residence time of water in the Curuá-Una Reservoir is about 40 days (Robertson,

1980: 10); Balbina's 355 day mean turnover time ‑‑ almost 10 times

longer ‑‑ means that water quality and corrosion problems will be

worse than at Curuá-Una. The greater

number of stagnant bays and channels at Balbina will further accentuate the

difference. At the rate experienced at

Curuá-Una, Balbina's maintenance can be expected to cost US$4.15 million per

year, or 4.3 mils (US) per kilowatt-hour of electricity delivered to Manaus

(about 10% of the tariff charged consumers).

In its first 13 years of operation, repairs due to similar corrosion in

the Brokompondo Dam in Surinam totaled US$4 million, or over 7% of the

construction cost (Caufield, 1983: 62).

As at Brokompondo and Curuá-Una, vegetation is being left to decompose

in most of the Balbina submergence area: only a token 50 km2 (2%) of the reservoir was cleared before the dam was closed.

The failure of

ELETRONORTE to clear the submergence area at Balbina is a matter of legal

controversy. Brazil's law number 3824 of

23 November 1960 states that it is 'obligatory to de-stump and clear the basins

of dams, reservoirs or artificial lakes.'

ELETRONORTE did not attempt such a clearing in the submergence area at

Tucuru' claiming that the law referred only to reservoirs intended for water

supply, not for power generation. The

precedent of Tucuru' was subsequently applied to justify not clearing at

Balbina A Crítica, 8 November 1985).

Prior to Tucuruí, the forest had been left uncut in the 86 km2 Curuá-Una Dam in Pará closed in 1976, and only 50% of the submergence

area was cleared in the 23 km2 Coaracy Nunes

(Paredão) Dam in Amapá closed in 1975 (Paiva, 1977). When vegetation left in reservoirs

decomposes, the water becomes acid and anoxic (Garzon, 1984).

THE ENVIRONMENTAL

FOLLY

(a) Impacts on

natural systems

Forest loss is one

of the primary environmental costs of large dams like Balbina. The potential value of the forest sacrificed

is not included in calculations of the reservoir's cost. Were non-wood forest products such as

pharmaceuticals exploited to their full potential the value of an area this

size could be substantial in purely financial terms. The area disturbed is much greater than the

2360 km2 actually flooded, since the inclusion of islands

roughly doubles the area affected.

Despite ELETRONORTE's promotion of the islands as having 'conditions for

life of animals and plants' (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, nd. (1987): 18), forest

divided into tiny fragments is known to lose many species of animals and plants

as the isolated patches degrade (Lovejoy et al., 1984).

The large area

flooded for little power is the most obvious indicator of extraordinary

environmental cost at Balbina. The area

to be flooded is not known with any certainty, despite the apparent precision

of ELETRONORTE maps and statements. The

topographic information in the maps, and in the area calculations derived from

them, is based on aerial photographs. The

photographs record the level of the tops of the trees in the forest, not the

ground underneath; since a substantial part of the reservoir will be only a

meter or two deep, errors of this magnitude can easily alter the final result. One indication that the topographic

information is only approximate is that more dikes had to be built than

originally anticipated to keep water from overflowing into adjacent drainage

basins (Antonio Donato Nobre, personal communication, 1987).

The possibility has

been suggested that the flooded area at the 50 m level might be about double

the area officially acknowledged.

'Sources in the economic sector of the federal government' reportedly

revised the area from 1600 to 4000 km2 (Barros,

1982). One congressman charged the

government with deliberately underestimating the area to be flooded A

Crítica, 29 December 1982).

ELETRONORTE promptly denied that the reservoir would flood more than

1650 km2. The origin of

the 1650 km2 figure is unknown, although it also appears in an early

forest survey report (Jaako Pöyry Engenharia, 1979: 3). Originally ELETRONORTE had expected the

reservoir to occupy only 1240 km2 when full (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/MONASA/ENGE-RIO, 1976: B-55).

The official figure for the reservoir area at the 50 m water level is

currently 2360 km2 (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b), almost

double the original value. The current

value was calculated in 1980 (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1981), and so does not

reflect any refinements in topographic information that may have been made

since that time. Engineers who worked on

Balbina's topographic survey have told INPA researchers that the survey's

margin of error is so great that a 4000 km2 reservoir is

within the range of possibility (Antônio Donato Nobre, personal communication,

1988). That the reservoir could flood an

area much larger than the official estimate has not been independently

confirmed; it remains only a persistent rumor.

Only actually filling the reservoir will reveal the impoundment's true

size.

The decomposition of

the vegetation in the water produces hydrogen sulfide gas (H2S), giving it a rotten smell.

The Brokompondo Reservoir in Surinam, which had vegetation left in a

shallow reservoir like Balbina, produced H2S that forced

workers at the site to wear masks for over two years after the dam was closed

(Melquíaides Pinto Paiva, personal communication, 1988; Paiva, 1977; Caufield,

1982). In the much smaller Curuá-Una

Reservoir in Pará the smell was even apparent to people overflying the area in

small airplanes (B. A. Robertson, personal communication, 1988). Despite the popular concern over this aspect

of the environmental impact, air pollution from H2S is a relatively temporary and restricted phenomenon. The shallow reservoir with a large area of

land alternately exposed and flooded will also produce methane gas

(CHU4D). Balbina has been suggested as a

potential contributor to this problem (Goreau and Mello, 1987). Methane contributes to the greenhouse effect

now warming global climate (Dickinson and Cicerone, 1986). Amazonia has recently been identified as one

of the world's major sources of atmospheric methane; the várzea

(floodplain) is the principal contributor (Mooney et al., 1987). The várzea occupies about 2% of

Brazil's Legal Amazon, or about the same percentage that would be flooded by

the 80 dams under consideration for construction in the region over the next

few decades. Were these reservoirs to

contribute an output of methane on the order of that produced by the várzea,

they would together represent a significant contribution to global atmospheric

problems.

Fish death at the

time of closing the dam is one of the impacts that attracts most

attention. ELETRONORTE has made it

difficult for observers to witness this aspect by not informing researchers and

others of when the dam would actually be closed. Balbina was closed without warning 30 days

before the announced date of 31 October 1987.

Some researchers were present at the time, however. Fish mortality occurred downstream of the dam

at Balbina (José A.S. Nunes de Mello, personal communication, 1988). In the case of Tucuru', ELETRONORTE closed

the dam without warning on 6 September 1984 ‑‑ one day before the

National Independence Day and a three-day holiday. An INPA team was able to reach the site by 10

September, and some fish mortality was observed. Fish mortality at Tucuruí occurred when water

was first allowed to pass through the turbines in a test prior to the

dedication ceremony. The blast of anoxic

water killed many fish in the area immediately below the dam; ELETRONORTE

removed these by truck in order to improve the visual and olfactory appeal of

the area for the dedication ceremony. At

Balbina, the turbine intakes at the very bottom of the reservoir will

inevitably take water virtually devoid of oxygen.

(b) Impacts on non‑indigenous

residents

Relatively few

people live in the Balbina area as compared to many other hydroelectric

projects. ELETRONORTE recognized only

one non-Amerindian family with 7 people in the submergence area and 100

families between the dam and the Abacate River, 95 km downstream. A survey by three organizations opposed to

the dam concluded that 217 families totalling over 1000 people would be directly

affected (MAREWA, 1987: 23). A business

publication favorable to the dam reported the non‑indigenous population

in the submergence area to be 42 people in 11 families Visão, 16 July

1986).

Part of the

Manaus-Caracaraí (BR-174) Highway would also be flooded; property owners in the

area calculated as likely to flood once in one‑thousand years are to be

paid compensation by ELETRONORTE. One

ELETROBRÁS report recognizes 65 properties and squatter claims in the reservoir

area, with a total of 250 people (Brazil, ELETROBRÁS, 1986b: 6-13). The non-indigenous residents of the Balbina

submergence area were offered land in a government settlement project.

Residents along the

river below the dam opted to stay where they were in exchange for benefits to

compensate for the loss of fish and potable water during the filling phase: the

50 families closest to the dam (those located above Cachoeira Morena, 30 km

below the dam) would be supplied with solar dryers for use in preserving the

fish expected to be trapped in ponds formed in the dry riverbed; these families

plus the 50 additional families between Cachoeira Morena and the Abacate River

would receive wells and water tanks.

ELETRONORTE only completed about one-third of the 100 wells before the

dam was closed. ELETRONORTE promised to

supply water from tank trucks to those who had not received wells (about half

were on lots with access to a road that had been built from Balbina to

Cachoeira Morena). Only one delivery of

water was actually made (Jaime de Araújo, personal communication, 1988).

The number of

downstream residents benefiting from the assistance program was reduced during

the course of dam construction.

Originally 177 families were interviewed downstream of the dam for

inclusion in the benefit program; a more detailed survey stopped at 151

families, indicating families only as far downstream as the Jatapu River, or

145 km below the dam (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1986a). The survey was halted in December 1986 when

ELETRONORTE decided to restrict assistance to the 100 families living above

Abacate River, 95 km below the dam. A

climate of distrust has prevailed between the downstream residents and

ELETRONORTE.

(c) Impact on

Amerindians

The flooding of

part of the area of the Waimiri-Atroari tribe is the most dramatic of the

reservoir's non-monetary costs. Two of

the tribe's 10 remaining villages will be flooded: Taquari (population 72) and

Tapupun~ (population 35) (Brazil, FUNAI/ELETRONORTE, nd. (1987): 11). This represents 29% of the tribe's

population, now totalling only 374 individuals.

This total is divided into 223 Waimiri and 151 Atroari (Brazil,

ELETROBR'S, 1986b: 6-12). The 107 people

in the two flooded villages are all Waimiris, representing 48% of the

population of this group. Since the

groups move within their territory to hunt and fish, the number affected is

greater than those in the flooded villages.

The area to be

taken from the reserve is calculated on the basis of the height to which the

reservoir is likely to reach with a frequency of once in 1000 years. The level so calculated is 53 m above

sea-level, or 3 m above the normal full level of the reservoir. Higher flooding is expected in the upper part

of the reservoir, where the reserve is located, because the narrow neck that

divides the Balbina reservoir into two parts (see Figure 1) restricts water

flow to the dam (Col. Willy Antônio Pereira, personal communication, 1987; see

Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1986b). It should

be noted that sedimentation will begin at the upper end of the impoundment. If sediments should partially block the

narrow passageway between the two parts of the reservoir, then the chance of

higher and more frequent floods in the Waimiri-Atroari area would be greatly

increased.

At the 53 m level

311 km2 of the reserve would be flooded (Brazil, ELETROBR'S,

1986b: 6-13). Of the presently proposed

reserve's 24,400 km2 area this

represents 1.3%. While the flooded

portion is very small as a percentage of the reserve area, it includes a

significant part of the tribal population and their food resources. The riverside fishing locations of the two

villages will not be moved inland when the riverbank is replaced with a

stagnant bay or a vast mudflat covered with the standing skeletons of dead

trees. The turtles whose eggs form a

staple of the tribe's diet have been prevented from reaching the area by the

dam now blocking their yearly ascent of the Uatumã River.

Brazil's agency for

Amerindian affairs (FUNAI: the National Foundation for the Indian) took a

delegation of Waimiri-Atroari leaders to visit the Parakan~ tribe, which had

had much of its territory flooded in 1984 by the Tucuru' Reservoir. The visit quickly convinced the Waimiri‑Atroari

that they would have to leave their villages and cooperate with FUNAI ‑‑

something oral explanations and a demonstration using a mock-up of a dam and

reservoir had failed to do. Two new

villages were built by the tribe itself elsewhere in the territory. The population that moved received a variety

of gifts from FUNAI, such as outboard motors and aluminum boats to replace

their traditional dugout canoes. The

individuals who have led in collaborating with FUNAI are not the traditional

tribal leaders; the sudden material wealth of the gift recipients has created

internal tensions within the tribe (see Adolfo, 1987). Anthropologists working in the area have been

shocked by the alacrity with which the recipients of the gifts have cast off

their former customs and lost their self-sufficiency (Arminda Muniz, personal

communication, 1987).

The moving of two

indigenous villages and loss of part of a reserve would be a small matter

against the background of affronts that Amerindians have suffered throughout

the region in recent years. The case of

Balbina is significant, however for two reasons: (1) the particularly dramatic

decimation of the tribe only a few kilometers from Manaus in the last decade,

and (2) the dependence of the Balbina project on foreign funding.

The tribe had a

population of 6000 in 1905 according to an estimate by the German naturalists

Georg Hübner and Koch-Grünberg (CIMI, 1979: 5; see also Garcia, 1985, MAREWA,

1987). By that time the tribe had

already suffered a long series of massacres.

The first official registry of a punitive expedition against the tribe

was in 1856, when a force of 50 soldiers eliminated several dozen Indians. Similar expeditions were mounted in 1872,

1873, 1874 and 1881 (Martins, 1982: 284).

The 6000

turn-of-the-century population was reduced to 3500 by 1973 through a long

series of violent encounters. In 1905

and 1906 punitive expeditions yielded body counts of 300 and 203 respectively;

each of these expeditions also captured several Amerindians as 'trophies' and

brought them to Manaus where they subsequently sickened and died (Martins,

1982: 284-286).

Violent contacts

have continued up to the present decade.

Deaths on the non‑Amerindian side of these encounters have

received wide reporting in Manaus, whereas those on the indigenous side have

not ‑‑ a pattern that reinforces the unsympathetic view of the

tribe among Manaus residents. In 1970

the Manaus-Caracara' (BR-174) Highway was begun to link Manaus with

Venezuela. The highway bisected the

tribe's territory; during and after the highway construction, access to the

area was restricted by the military. In

1973 travel on the highway through the tribal area was prohibited, and for at

least five years thereafter traffic was restricted to convoys of vehicles

during daylight hours. Violent contacts

continued; on 29 December 1974 Gilberto Figueiredo Pinto Costa, the FUNAI agent

who was the only non-Amerindian to have become friendly with the tribe and

visit their villages, was killed, allegedly in Waimiri-Atroari attack on the

Alalaú-II outpost (NB: some FUNAI employees reportedly believe that he was murdered

by other employees of the agency who feared what he knew of their participation

in massacres: see Athias and Bessa, 1980).

In 1975 FUNAI decided that so many hostile encounters had taken place

that the agency's efforts to 'pacify' the tribe were suspended (Martins, 1982:

278). The following year ELETRONORTE

contacts with FUNAI began in order to clear the area for Balbina (Garcia,

1985). The 3500 population in 1973 (an

estimate made by Gilberto Pinto) was reduced to 1100 by 1979 (by FUNAI estimates,

see Athias and Bessa, 1980), and further to 374 ‑‑ mostly children ‑‑

by 1986. As Garcia (1985) states: 'in

twelve years more than three thousand Indians disappeared, killed by epidemics

of measles or by the bullets of adventurers, hunters and the gunslingers hired

by large landholders, with the clear support of federal and state

authorities.' These events are not

academic facts from a distant historical period; they have occurred a mere 200

km from Manaus over a period that most of the city's adult population can

remember.

The Waimiri‑Atroari

tribe's reserve has been decreased whenever this proved convenient. The reserve was created by Decrees 69.907/71,

74.463/74 and 75.310/75 (of 1971, 1974 and 1975). In 1981 President Figueiredo revoked these through

process BSB/22785/81 when he signed decree 86.907/81. This abolished the reserve, transforming it

into a mere 'temporarily interdicted area for the purpose of attraction and

pacification of the Waimiri-Atroari Indians' (Brazil, FUNAI/ELETRONORTE. nd.

(1987): 15). In this transformation the

area not only lost some of its legal protection but also decreased by 526,000

ha, which was given to Timbó Mineradora Ltda ‑‑ a subsidiary of

Parapanema, the firm that is mining cassiterite at Pitinga in the upper reaches

of the Balbina catchment. The area given

to the mining company was very briefly slated for return to the tribe when it

was included in an area identified for a reserve by the interministerial group

in charge of indigenous areas A Crítica, 9 June 1987); this was quickly

declared an 'error' by FUNAI and the reserve was proposed without the mining

area A Crítica, 10 June 1987).

ELETRONORTE funds are helping speed the demarcation of the reserve by

surveying and marking its borders on the ground.

The key event in

transforming Balbina from a sheaf of papers into a 2360 km2 reality of bleached tree trunks and foul smelling water was the

Brazilian-French accord signed by Brazilian president Ernesto Geisel and by

French president Valery Gisgard D'Éstang during a visit to Brasília in

1978. The French were sharply attacked

by Amerindian rights groups for having signed an agreement that would flood

tribal lands; the French responded that the Brazilian government had assured

them that there were no Amerindians in the area A Folha de São Paulo, 8

October 1978). Information on the

existence of the Waimiri-Atroari was not difficult to obtain at the time.

Because of the

impact on the Waimiri-Atroari implied by the plans for Balbina, France and Brazil were accused of genocide at

the Fourth Bertrand Russell Tribunal in Rotterdam in November 1980. Severe as the impacts of the reservoir may

be, its classification as 'genocide' is probably colored by the massacres

associated with (Brazilian) roadbuilding activities in the tribe's territory

during the period when Balbina was being planned, especially 1974-1975. ELETRONORTE officials are quick to point out

the unfairness of criticizing Balbina for flooding a small part of tribe's

territory when nothing is said about outright liquidation only a few kilometers

away (Adelino Sathler Filho, personal communication, 1987). However, the background of nearby atrocities

does not alter the fact that Balbina will have a negative impact on the

surviving Waimiri-Atroari. International

sources providing the dam's financing have apparently not considered this

impact. Although the French government

appears to have no qualms about impacts on indigenous groups, the World Bank

has announced a set of policies requiring that heavy consideration be given to

any effects that loans may have on tribal peoples (Goodland, 1982).

5. THE ECONOMIC

FOLLY

(a) The Brazilian-French Accord

The Brazilian‑French

accord provides for technical assistance and a special credit line for

purchasing the turbines from France. The

first turbine was made in France by Neyrpic, a company belonging to the Creusot

Loire Group; the other four turbines are being made in Taubat' (in the state of

São Paulo) by Mec^nica Pesada, a Brazilian subsidiary of the same Creusot Loire

Group. The turbines cost more than

originally expected, partly because the type of steel used was changed to a

kind more resistant to corrosion by acid water.

The temptation to

order more turbines and generators than necessary is great when purchase

agreements for these form a part of a generous financing package: Paulo Maluf,

former governor of São Paulo, provoked a major financial scandal when it was

discovered that more turbines had been purchased than needed for the Três

Irmãos Dam Isto É, 3 September 1986).

The Três Irmãos turbines came from the same French factory that supplied

Balbina's imported turbine. Although

five 50 MW turbines on a river as small as the Uatumã is considered

'supermotorized' by ELETRONORTE, officials insist that it is within the normal

range. Two justifications are cited: (1)

the fact that power demand in Manaus so greatly exceeds the dam's generating

capacity that all power can be sold (most dams pass water over their spillways

during flood season because extra power is not needed), and (2) the lack of a

regional network to cover demand during periods when one of the turbines is

under repair. Rather than 10% excess

installed capacity, the Brazilian norm in a regional grid, a full spare turbine

is planned for Balbina i.e. 20% excess capacity). ELETRONORTE's histogram of anticipated energy

production over time indicates that all five turbines would operate for at most

one month per year, and the dam could operate with four turbines for only one

additional month during the flood season (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b). While Balbina may well fall within

ELETRONORTE's standards for receiving five turbines, the built-in temptation to

order more imported equipment than necessary represents an unfortunate generic

characteristic of financing arrangements of this type. Decision‑making procedures should be

adopted that avoid any possible influence from the firms supplying goods and

services to development schemes.

(b) Costs of the

Rush to Fill the Reservoir

The most evident

waste from ELETRONORTE's haste to fill the reservoir is the loss of the

forest. Forest products such as rubber

and rosewood were being exploited up to the last months before filling. The most valuable potential products of the

forest here (as elsewhere in Amazonia) have hardly even been identified,

especially pharmaceutical compounds (see Myers, 1976). The easily-marketed timber species, however,

represent a loss that is immediately apparent to the general public e.g.

A Crítica, 22 September 1984, 3 October 1985). A timber survey by INPA revealed 28.8 m3 of valuable wood per hectare (Higuchi, 1983: 20), or approximately 6.8

million m3 in the 2360 km2 reservoir

area. A survey by a consulting firm

concluded that wood volume of all species averaged 161 m3/ha for trees over 10 cm diameter at breast height (DBH) and 58 m3/ha for trees over 50 cm DBH (Jaako Pöyry Engenharia, 1983: 50). This reportedly was regarded as insufficient

and discouraged logging efforts Visão, 16 July 1986). The short notice given to potential logging

contractors also made any serious commercial exploitation unlikely: logging

firms had less than two years time between the date that bids were solicited

and the original date set for closing the dam.

The inability of

ELETRONORTE to interest commercial logging firms in exploiting the reservoir

area represents an embarrassment given the high visibility of the loss

involved. The president of ELETRONORTE

emphasizes that the flooded timber is not lost, suggesting that during the

low-water period loggers can cut the trees on the exposed ground and return by

boat to tow the logs away during the high-water period (Lopes, 1986). Officials at Balbina say that loggers could

cut the dead trees standing in the shallow water. At Tucuruí some loggers have done this for

valuable species; the costs are much lower than for traditional dry-land

logging because of the ease of towing away the cut logs. The danger is great for the person sawing the

trees, however. When trees die standing

in pastures in Amazonia they are left untouched because of the danger of dead

branches falling on anyone who saws the trunk below.

The order in which

the various parts of the project are constructed could have been changed with

possible environmental benefits and financial savings. The transmission line is the last item being

built, whereas if this had been the first item, thermoelectric plants at the

dam site could have used the wood in the future reservoir area and transmitted

the energy to Manaus. Above‑ground

biomass dry weight estimated as a weighted average over the forest types in the

area is 400 m tons/ha (Cardenas, 1986b: 27).

Considering the percentage of the total represented by trunks in the

sample plots (Cardenas, 1986b: 16), the dry weight of trunks would average 267

m tons/ha, or 63 million m tons in the 2360 km2 submergence area. Plans for

woodburning powerplants to be installed in small cities in the state of

Amazonas have considered wood to contain an average of 2500 Kcal/kg and power

generation to require 4000 Kcal/kWh of electricity (Brazil, CELETRA,

1984). The trunks of the trees to be

flooded at Balbina are therefore equivalent to approximately 39.4

gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electricity. To

generate this from petroleum with the mix of diesel and fuel oil used in Manaus

would require the equivalent of over 161,000 barrels of crude oil (calculated

from Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1985c: 19), worth US$2.4 million at the present low

price of US$15/barrel.

Generation of power

from firewood is not without costs and technical difficulties. In September 1987, slightly over a year

before hydroelectric generation was officially scheduled to begin, the 7.5 MW

wood-burning plant that supplied the Balbina construction effort was deactivated

and replaced with diesel generators; the woodburning plant will be dismantled

and sent to another hydroelectric project.

ELETRONORTE has abandoned its plan to install two 25 MW wood‑burning

thermoelectric plants at the dam site to use wood extracted after flooding the

reservoir. The parts for these power

plants, which were already arriving at Balbina, were transferred to Manaus for

conversion to an oil-fueled supplementary plant there. High oil prices had made the thermoelectric

plants a priority in the early 1980s, but the subsequent price decline has

removed much of this incentive. The low

price of oil is the key factor in the change of plans, not sudden awareness of

the value of maintaining forest.

Despite the

noncompetitiveness of using firewood instead of oil at the current low oil

prices, it should be remembered that oil represents a physical resource, not

merely a given amount of money. By

throwing away the forest that could be used for power generation instead of oil

today one is also throwing away the opportunity to keep that amount of oil in

the ground until the time when petroleum is in short supply and, consequently,

its price is much higher. Using the

forest in the submergence areas also would reduce the water quality problems caused

by rotting vegetation in the impoundments.

Any plan to convert forest biomass in future reservoirs to

thermoelectric power should be accompanied by strict requirements that the

power plants be moved elsewhere once the submergence areas have been harvested,

lest the plants contribute to deforestation beyond the limits of the

reservoirs.

6. ALTERNATIVES TO

BALBINA

Balbina is

particularly unfortunate because it is unnecessary. The dam is expected to produce firm power

that could be counted on for only about one‑third of the 218 MW 1987 level

of power demand of Manaus (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b); the average power

delivered in Manaus (109.4 MW after 2.5% transmission loss) would be half the

1987 demand. In relation to the

approximately 130 MW actually consumed in 1987 it represents 84%. The dam will never supply this percentage

(50%) of the Manaus demand because the calculations assume the 50 m reservoir

level ‑‑ at first the dam will generate a substantially lower

amount (a figure not yet disclosed by ELETRONORTE) because the reservoir level

is supposed to be kept at 46 m until water quality stabilizes. However, ELETRONORTE statements in 1988

indicate that the promise to hold the level at 46 m may be broken, to fill the

reservoir to capacity as soon as water availability permits.

The percentage of

power consumed in Manaus supplied by Balbina will shrink with each succeeding

year as the city continues to grow: Balbina's average output (at the 50 m

level) delivered to Manaus corresponds to only 38% of the 285 MW annual power

consumption, or 26% of the 420 MW annual power demand that ELETRONORTE projects

for the city in 1996 when another dam, to be built 500 km from Manaus at

Cachoeira Porteira on the Trombetas River, is expected to make up the city's

power deficit (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987b).

Cachoeira Porteira is to have 1420 MW of installed capacity and produce

an average of 760 MW (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1985b), or about seven times that of

Balbina. Only one dam (Cachoeira

Porteira) could have been built ‑‑ with half the cost and half the

impact ‑‑ rather than building both dams.

The futility of

Balbina becomes even more apparent when one considers that natural gas 500 km

from Manaus in the Juruá River basin could supply Manaus with power. This is proposed as an alternative to Balbina

by Brazil's leading expert on energy matters, José Goldemberg (1984; see also

Melchiades Filho, 1987). Recent

discovery of oil and gas at Urucú, nearer Manaus, could also supply the city

with power without Balbina (see Falcão Filho, 1987). The magnitude of the Juruá gas deposits only

became apparent while Balbina was under construction. Even so, Balbina's construction could have

been stopped years before completion, saving several hundred million dollars

that would be better spent on transmitting energy from Juruá. Preliminary studies have even been made for

transmission of power from Juru' to the Grande Carajás area in eastern

Amazonia, where it would be used in pig-iron smelting. The distance traversed in such a scheme would

be much greater than from Juruá to Manaus.

The 500 km distance from Manaus to the Juruá gas fields is about the

same as the distance from Manaus to Cachoeira Porteira, although transmission

from Juru' would require the additional expense of crossing either the Amazonas

(Lower Amazon) or both the Solimões (Upper Amazon) and the Rio Negro. Building a dam is also expensive,

however. Gas pipeline routes have also

been proposed from Juruá (Brazil, CEAM, 1985) or from Urucú (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE, 1987c, p. Amazonas-6). The

president of ELETRONORTE has reportedly stated that it was a decision of the

population of Manaus to build Balbina rather than use gas or build transmission

lines, and that generating from gas and building transmission lines are

technologically feasible (Lopes, 1986).

No public debate on energy options was held, however, since Balbina was

begun at a time when Brazil's military regime limited such discussions (see

Brazil, INPA, Núcleo de Difusão de Tecnologia, 1986).

Transmission from

major hydroelectric generating areas in the Tocantins, Xingu and Tapajós River

basins is also possible. These large

tributaries flow into the Amazon River from the south, descending from Brazil's

central plateau. Their power generating

potential is enormous, and if dams in the area described in the 2010 plan are

built, Brazil will have the luxury of more power than it can use. Dams in that region would cause major

environmental impacts as well, but the area flooded per megawatt of energy

produced would be much less than at Balbina.

Constructing transmission lines to these hydroelectric sites would

provide a virtually permanent solution to power supply for Manaus, and would be

cheaper than Balbina has turned out to be.

Part of the

distance from Manaus to Tucurui and other hydroelectric sites on the rivers

south of the Amazon will be provided with transmission lines anyway because the

Cachoeira Porteira Dam lies along one of the possible routes. The lines from Balbina also make up part of

this trajectory. A study by ELETRONORTE

done in about 1976 estimated that building a transmission line from Tucuru' to

Cachoeira Porteira would cost US$600 million (Joaquim Pimenta de Arrila,

personal communication, 1987). This is

cheaper than the US$730 million spent for Balbina.

About half of the cost

of a Tucuruí-Cachoeira Porteira link would be for crossing the Amazon

River. The crossing could not be done

with a submerged cable because of the river's strong current. For a suspended line, the river is too wide

for crossing in a single span even at its narrowest point in Óbidos ‑‑

the towers required would be too high to be practical. The crossing would therefore be made at a

wide, shallow point using either a chain of towers built in the river bottom or

a system of floating towers. Possible

locations for such a crossing are at Almeirim (Pará) and Itacoatiara

(Amazonas). Direct current would be used

for the crossing; the electricity would be converted to and from alternating

current in substations on either side of the river at a cost of about US$100

million per substation. About 1200 km of

roads that would have to be built along the lines from Tucuruí to Manaus via

Itacoatiara would cost about US$120 million (Joaquim Pimenta de Arrila,

personal communication, 1987). Advances

in power transmission technology since these estimates were made could lower

the costs substantially (Pires and Vaccari, 1986).

Preliminary plans

for the Altamira Complex on the Xing' River include maps implying that

transmission lines would link Altamira and Cachoeira Porteira (Brazil,

ELETRONORTE/CNEC, nd. (1986): 36), apparently via 'bidos. One ELETRONORTE map of expansion plans for

transmission lines indicates a link between Tucuru' and Monte Dourado inthe

Jari Project area north of the Amazon River, with a crossing at the shallow

stretch of the river near Almeirim (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987c, p.

Pará-30). This would leave a stretch of

about 520 km to link Almeirim with Cachoeira Porteira. Another map indicates links between Altamira

and Itaituba to be completed in 1989 and between this line and Santarém to be

completed in 1990 (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987c, p. Pará-29). These would greatly reduce the distance

needed for a link to Cachoeira Porteira, which is about 305 km from Santarém

via Óbidos (if, in fact, it is feasible to cross the Amazon River at this

narrow point.) Since the 190 km

transmission line from Manaus to Balbina is expected to cost US$33 million A

Crítica, 11 June 1985), the US$174,000 cost per kilometer implies costs of

US$53 million to link Cachoeira Porteira with Santarém or US$90 million to link

Cachoeira Porteira with Almeirim (exclusive of the river crossing). Including US$300 million for crossing the

Amazon river would bring the cost to about half of the US$730 million spent on

Balbina (46% or 53% depending on the route).

Providing power

from alternative sources is not the only way to substitute for the 109.4 MW

average power that Balbina would deliver to Manaus. Energy conservation could reduce the need for

a substantial percentage of the power used.

Except for efforts to discourage use of gasoline, Brazil has done little

to promote energy conservation (see Goldemberg, 1978). Electrical appliances and industrial equipment

could be made much more efficient with modifications already in use in other

countries (Goldemberg et al., 1985).

Especially in the case of Manaus where energy is supplied from high-cost

sources such as Balbina, eliminating inefficient uses of energy is the logical

first step (see Branco, 1987). Even

under average conditions in developing countries, rather than the extreme case

of Balbina, investment in increasing energy efficiency is much more

cost-effective than investment in new generating capacity (Goldemberg et al.,

1985).

In addition to

alternative solutions to power supply for the population of Manaus, at a

national level the very decision to locate a city of this size in Manaus is

questionable. Throughout Brazil,

adequate employment opportunities must be given to urban residents, including

those who are attracted from the countryside.

Much more could be done to expand the total supply of industrial

employment in Brazil. This expansion may

not be wisest in Manaus, however. For

example, both the 12,600 MW hydroelectric dam at Itaipú and the 8000 MW dam at

Tucuruí have only a fraction of their generating capacities installed. More power could be had by simply mounting

the remaining turbines and generators, without incurring any of the

environmental and financial costs of building more dams and creating more

reservoirs. Since both of these dams

have transmission links to the cities in migrant source areas such as Paraná,

the power could attract new factories that would employ some of the migrants

that now leave for Amazonia, especially Rondônia.

It is unrealistic

to think that Brazil can adopt agricultural patterns similar to those in North

America and still keep over 30% of its population in the rural zone. The rural population of the United States,

for example, declined over the course of this century from a proportion similar

to that of Brazil to less than 5% today.

If scarce capital resources are to create a vastly increased number of

urban jobs in Brazil the location of cities must be planned more rationally

than at present. Manaus, for example,

has grown from approximately 120,000 in 1967 to about 1.3 million in 1987

because of population drawn to industries that have located themselves in a

special duty-free zone. The city must

now be provided with energy, which is being done by building Balbina;

construction cost will total US$3000 per kilowatt of installed capacity. Similarly, the Samuel Dam in Rondônia, being

built to provide power to that new state whose population has been swollen by

migration along the World Bank‑financed BR-364 Highway, will cost US$2800

per kilowatt installed because, like Balbina, it is on a small river in a flat

region inappropriate for hydroelectric development. For comparison, when completed, Tucuru' will

cost US$675/kilowatt (4.6 times less than Balbina) and Itaip' US$1206/kilowatt

(2.6 times less than Balbina) (construction costs from Veja, 20 May

1987: 30). In other words, the same

investment in a more topographically favorable site could produce several times

more power, and generate proportionately more industrial employment. That employment could absorb many of the

migrants now being forced to leave Southern Brazil for Amazonia.

Brazil's policy of

a 'unified' tariff for electricity means that industry and population can

locate themselves where they choose, and the power authority is then obliged to

take heroic measures to provide them with electricity. Power in unfavorable places like Manaus is

subsidized by the consumers living nearer favorable sites like Itaipú. Were electricity sold at rates reflecting its

cost of generation, industrial centers would relocate themselves nearer the

better hydroelectric sites, thereby significantly increasing the total amount

of urban employment.

Power tariffs in

Brazil are, on average, much lower than the cost of energy production. This discourages energy conservation and

provides substantial subsidies to energy-intensive industries such as aluminum

smelting. Aluminum production in the

Grande Carajás Program area is particularly favored, since ELETRONORTE has

agreed to supply power to the plants at a rate tied to the international price

of aluminum, rather than to the cost of producing the energy: for the

ALUNORTE/ALBRÁS plant in Barcarena, Pará (owned by a consortium of 33 Japanese

firms together with Brazil's Companhia Vale do Rio Doce), only US 10 mils/kWh

is charged, while the power, which is transmitted from Tucuruí, is estimated to

cost US 60 mils/kWh to generate (Walderlino Teixeira de Carvalho, public

statement, 1988). The rate charged the aluminum

firms is roughly one-third the rate paid by residential consumers thoughout the

country, and so is heavily subsidized by the Brazilian populace both through

their taxes and their home power bills.

ALBRÁS consumed 1673 GWh of electricity in 1986, or 1.7 times as much as

the city of Manaus consumed in the same year (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987c, pp.

Amazonas-23, Pará-12). Expansion plans

will more than triple the annual consumption by ALBR'S to 5225 GWh by the end

of the decade (Brazil, ELETRONORTE, 1987c, p. Pará-19).

The United States

representative on the World Bank Board of Executive Directors, who led an

unsuccessful attempt to defeat the Brazilian Electric Power Sector Loan in

1986, described Balbina as an example of 'totally unacceptable investments'

both because of environmental concerns and the lack of any requirement that

Brazil's electrical sector raise its tariffs sufficiently to cover its costs

(Foster, 1986). Although not a condition

for its loans, the World Bank has been urging Brazil to increase tariffs in

order to give the power monopoly a profit of at least 6% (O Globo, 4

February 1988). ELETRONORTE has little

motive to transform itself into a highly profitable operation because the

enterprise is legally required to give any profits over 10% to the national

treasury as part of the 'Global Guarantee Reserve,' or 'R.G.G.' This cap on profitability has been suggested

as an explanation for why the company's executives have often opted for

expensive and inefficient investments (Veja, 12 August 1987: 26). ELETRONORTE runs little risk of making a

profit at Balbina.

7. DAM BUILDERS AS AN INTEREST GROUP

Pressure to build

dams such as Balbina comes in large part from those directly involved in

constructing them: the barrageiros or 'dam builders.' Not only do the vast sums of money involved

attract powerful lobbying efforts on the part of construction firms and

entrepreneurs, but the engineers and other staff making up the unique barrageiro

subculture in Brazilian society go to great lengths to influence popular

opinion in favor of the dams. Mostly

from southern Brazil, the barrageiros move from project to project

living in comfortable but remote colonies built at each site. The social relations of the Balbina colony to

the city of Manaus are strikingly parallel to the relations that American

'zonies' (who until recently ran the Panama Canal) had with the wider society

of Panama. Life in the colony can appear

idyllically free of the social problems of the rest of Brazil ‑‑ a

situation maintained by armed guards who prevent any laborers from entering the

'class A' residential areas at any time other than specified periods on the

weekends. Adjoining residential 'vilas'

(without a physical barrier) separate 'class A' employees with a

university-level education from those without this distinction; each vila is

provided with separate schools. Separate

social clubs (the 'Waimari' and the 'Atroari') separate engineers from other

categories: mere scientists are not allowed in the engineers' club. One price of these barriers is the many lost

opportunities to benefit from inputs from beyond the confines of the barrageiro

subculture. Another is the creation of a

strong interest group that battles furiously any who question the wisdom of

Balbina ‑‑ any doubt is perceived as a threat to the barrageiro

way of life.

8. BALBINA AND SCIENCE POLICY

Balbina and other

hydroelectric dams have had a strong and not always beneficial effect on

Brazilian science and science policy.

The availability of money and employment through ELETRONORTE and its

associated consulting firms has guided much of the research undertaken in

Amazonia because almost no funds can be obtained to support research through

traditional channels such as the National Council for Scientific and Technological

Development (CNPq) and the budgets of research institutions and universities.

Much of the

research done is simply collection of specimens, making of lists and

preparation of reports.

Hypothesis-oriented research is virtually nonexistent. The information is centralized within

ELETRONORTE to the point where one frequently encounters people both inside and

outside of ELETRONORTE who do not have information directly relevant to their

assigned tasks. For example, the

engineer responsible for alleviating downstream effects of closing the dam had

no information on the discharge of the various streams entering the Uatum~

River below the damsite ‑‑ the survey had been done by one of the

consulting firms and the report was unavailable at Balbina. ELETRONORTE headquarters at Balbina has no

library: even ELETRONORTE's own engineers can only consult the reports of the

various consulting firms and research groups by sending a written request to

the Brasília office. Many reports are

even rarer than medieval manuscripts copied by hand: only three copies exist of

one report on macrophytes at Tucuru' according to the secretary who curates the

original at INPA.

The role of

research in planning, authorizing and executing major engineering projects such

as hydroelectric dams is a critical matter if decision-making procedures are to

evolve that prevent the kinds of misadventures that now characterize so much of

the development process in Amazonia. The

public relations focus of many environment‑related activities, such as

the highly publicized effort to rescue drowning wildlife, is a matter of

intense controversy. Moving wildlife to

forest outside the submergence area yields little net benefit in terms of

animal lives saved: the animal populations already present normally compete

with the newcomers so that numbers of each species quickly decline to

approximately their former levels. At

Balbina the wildlife rescue operation, called Operação Muiraquitã, is