ABSTRACT

Soils in Brazilian Amazonia may contain up to 136 Gt of carbon to a depth of 8 m, of which 47 Gt are in the top meter. The current rapid conversion of Amazonian forest to cattle pasture makes disturbance of this carbon stock potentially important to the global carbon balance and net greenhouse gas emissions. Information on the response of soil carbon pools to conversion to cattle pasture is conflicting. Some of the varied results that have been reported can be explained by effects of soil compaction, clay content and seasonal changes. Most studies have compared roughly simultaneous samples taken at nearby sites with different use histories (i.e., 'chronosequences'); a clear need exists for longitudinal studies in which soil carbon stocks and related parameters are monitored over time at fixed locations. Whether pasture soils are a net sink or a net source of carbon depends on their management, but an approximation of the fraction of pastures under "typical" and "ideal" management practices indicates that pasture soils in Brazilian Amazonia are a net carbon source, with an average release of 11.1 t C/ha, or 6.7 X 106 t C for pastures from forest felled in 1990.

I.) INTRODUCTION: THE TROPICAL SOIL CARBON CONTROVERSY

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has so far not encouraged inclusion of carbon fluxes from soils under cleared tropical forests in the national inventories now being compiled under the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC). The reporting instructions state that "There is no scientific consensus on whether clearing leads to significant soil carbon loss in tropical forests. This calculation is optional for tropical forests" (IPCC/OECD Joint Programme, 1994: Vol. 2, p. 5.10). The instructions explain that "The basic calculations allow but do not encourage estimation of soil carbon loss after clearing of tropical forests. There are research results which indicate that conversion of tropical forests to pasture may or may not result in loss of soil carbon" (IPCC/OECD Joint Programme, 1994: Vol. 3, p. 5.27). This is based on citation of a series of studies, some of which indicate losses of soil carbon (Bushbacher, 1984; Cerri et al., 1991; Fearnside, 1980a, 1986a), and some of which do not (Lugo et al., 1986; Keller et al., 1986), pointing out that the last of these indicates "that clearcutting of tropical forests does not appear to release soil carbon" (IPCC/OECD Joint Programme, 1994: Vol. 3, p. 5.45). However, the study in question (Keller et al., 1986: 11,798) did not measure soil carbon or draw inferences about it, but rather measured net emissions of CO2 and other gases from soil under forest and in an adjacent unburned clearcut (without pasture grass). Emissions are not the same as changes in carbon stocks: the emission of carbon can remain unchanged while reduction of the rate of carbon input to the soil results in a drawdown of the carbon stock. In the case of the study by Lugo et al. (1986), an increase in carbon storage was found in pasture soils in Puerto Rico, especially in drier sites.

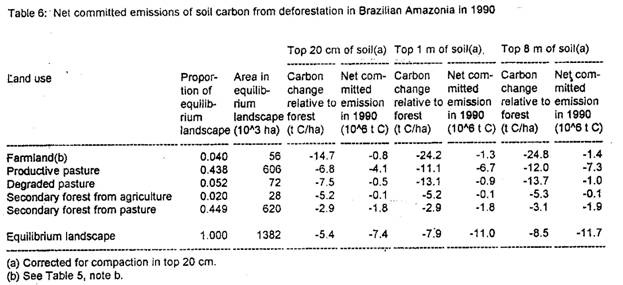

II.) LAND-USE CONVERSION IN BRAZILIAN AMAZONIA

The cumulative area deforested in Brazilian Amazonia (Fig. 1) is estimated to have reached 470 x 103 km2 by 1994 (Brazil, INPE, 1996; see Fearnside, 1997a). Of this total, approximately 45% (assuming 1990 values) was occupied by actively grazed cattle pastures from conversion of tropical forests, 28% was post-1970 secondary forest derived from abandoned pasture, and 2% was degraded pasture (Fearnside, 1996). The remainder was farmland (5%), post-1970 secondary forest derived from farmland (2%), and pre-1970 secondary forest (17%). As long as pasture is maintained for cattle, it is subject to periodic fires that can affect biogeochemical cycles and climate due to their emissions of trace gases such as CH4, CO, N2O and NOx (CO2 is also emitted from above-ground biomass, but, unlike the trace gases, the amount emitted is later reabsorbed when the pasture regrows). The conversion of forest to pasture causes large net releases of carbon (mostly from biomass) in the form of CO2, in addition to trace gases (Fearnside, 1997b).

[Fig. 1 here]

Carbon stocks in replacement vegetation biomass and original forest remains that are present in the converted system have received attention in a variety of estimates of carbon dynamics (Buschbacher, 1984; Uhl and Jordan, 1984; Uhl et al., 1988; Uhl and Kauffman, 1990; Fearnside, et al., 1993; Kauffman et al., 1995; Barbosa and Fearnside, 1996). In addition to biomass, soils in the tropics also represent an important storage compartment and potential source of carbon release to the atmosphere (Lugo et al., 1986). The upper 1 m of the world's soils has been estimated to contain 1220 Gt of organic carbon (Sombroek et al., 1993). Tropical soils account for 11-13% of all carbon stored in the world's soils (Brown and Lugo, 1982; Post et al., 1982). Soils under the original vegetation in the Brazilian Legal Amazon to a depth of 1 m are estimated to have contained 47 Gt C, of which 21 Gt C (45%) were in the top 20 cm (Moraes et al., 1995).

Carbon below a depth of 1 m has traditionally been regarded as inert, and presumed to be unaffected by changes in land use. However, Nepstad et al. (1994) have presented isotopic evidence indicating that up to 15% of the deep soil (1-8 m depth) carbon stock turns over on annual or decadal time scales, and that the loss of deep roots by replacement of forests with pastures could release substantial amounts of carbon over time scales as short as a decade. The study by Nepstad et al., (1994), near Paragominas, Pará, indicated that including the carbon stock between 1 and 8 m depth increases the total stock by a factor of approximately 2.9 relative to the stock in the top meter. A previous estimate based on extrapolation to 5 m depth of a 3 m profile near Manaus had estimated the total stock to be increased by a factor of 1.8 relative to the stock in the top meter (Cerri and Volkoff, 1987: 37). The results of Nepstad et al. (1994) imply that the soil to 8 m depth in the Legal Amazon contained (prior to changes in the portion of the region that is now cleared) a total stock of soil carbon of 136 Gt. This value undoubtedly overestimates the true one as not all soils in the region reach 8 m in depth. Soils in Central Amazonia and in the Solimões (Upper Amazon) basin are less deep than those of the Paragominas area (W.G. Sombroek, personal communication, 1997). Estimates of soil depth and deep layer carbon stocks are needed for each soil type in order to derive a better estimate for the soil carbon stock in the region as a whole. However, the carbon stock is clearly sufficiently large that even small percentage changes in these stocks would translate into fluxes large enough to be climatically significant, indicating the importance of reducing uncertainty concerning the amount, and even the direction, of soil carbon changes resulting from deforestation.

III.) SOIL CARBON CHANGES

A.) SHORT-TERM EFFECTS OF CONVERSION

The carbon stock in any soil is the result of a balance between inflows and outflows to the pool; in the case of tropical soils, the rates of both inflow and outflow are substantially higher than is the case in other parts of the world, making tropical soil carbon stocks respond rapidly to any changes in the flux rates. Small increases in temperature can substantially increase the rate of soil respiration in the tropics, leading to rapid drawdown of carbon pools (Townsend et al., 1992). The conclusion of Townsend et al. (1992) that large carbon emissions from tropical soils could result from the temperature increases expected from global warming apply equally well to the soil temperature increases that result when forests are converted to pastures.

Burning generally does not produce soil temperatures sufficient to oxidize carbon directly (Sánchez, 1976: 373). However, where heavy logs burn or vegetation is piled up, the soil temperature increases substantially (Zinke et al., 1978: 144; see also Nye and Greenland, 1960: 70). Soil sampling can easily miss this, either by deliberate avoidance of these 'atypical' microsites, or by a low number of samples (sometimes relying on a single soil pit). Studies are lacking that estimate the percentage of area of each type under sample points and stratify soil sampling among microsites of differing burn intensity.

Despite the small long-term effect of burning on soil carbon, short-term changes can result from the effect of the burn on the microbial biomass of the soil. Laudelot (1961) and Suares de Castro (1957; cited by Sánchez, 1976: 373) report sharp microbial biomass decreases following burns in shifting cultivation systems. Cerri et al. (1985) found that deforestation followed by burning eliminated all of the microbial biomass from the top 10 cm of soil, and two-thirds of the total in the soil profile. Any decrease in soil carbon as a direct result of killing microbial biomass would be small: the carbon stock in this compartment under natural forest in Capitão Poço, Pará has been found to be only 1.3% of the total carbon stock in the top 15 cm, where all of the microbial biomass is concentrated (Cerri et al., 1985). During the period when the microbial biomass remains depressed, the net rate of carbon accumulation in the soil should increase because soil respiration would be reduced. Following the initial decrease, the microbial population is believed to rebound to a level higher than it was prior to the burn (Nye and Greenland, 1960: 72).

The instantaneous release of carbon from the top 20 cm of soil due to burning pasture is ephemeral (Barbosa, 1994). Kauffman et al. (nd) also found no difference in the stocks of carbon pre-burn (36.2 t C/ha) and post-burn (36.4 t C/ha) in the top 10 cm of soil under a pasture under typical management in Marabá, Pará. However, other studies in Amazonia have found net reduction in carbon stocks in the soil in different systems in measurements made within a short time after burning (< 1 year). For example, in burning secondary forests of different ages in Altamira, Pará, Guimarães (1993) found a mean loss of 36 t C/ha from the top 20 cm of soil after burning. Cerri et al. (1991: 254), working near Manaus, Amazonas, found a 9 t/ha soil carbon release in the 0-20 cm layer (without correction for compaction) from conversion of primary forest to burned forest, and an additional 3 t/ha release by the time the pasture was one year old. Kauffman et al. (1995) found a reduction of 7.2 t C/ha near Marabá, Pará and 5.8 t C/ha in Santa Barbara, Rondônia in the top 10 cm of soil in an initial burn. Barbosa (1994) found a loss of 2.6 t C/ha in the top 20 cm when pasture was burned in Apiaú, Roraima.

B.) ESTABLISHMENT OF A NEW EQUILIBRIUM

The instantaneous release of soil carbon at the time of burning is followed by establishment of a new equilibrium over the medium to long term. Studies of medium and long-term changes (> 1 year) indicate mixed results on the increase or decrease of soil carbon when tropical forests are converted.

Some authors have considered this stock to be stabilized below the level in primary forest (Cunningham, 1963; Falesi, 1976; Hecht, 1982; Sánchez et al., 1983; Allen, 1985; Mann, 1986). Fearnside (1997b, using data from Paragominas, Pará, by Falesi, 1976 and Hecht, 1981) found a soil carbon release of 3.92 t C/ha (a value revised in this paper based on alternative bulk density values). Veldkamp (1994) found a net loss of 2-18% of in carbon stocks in the top 50 cm of forest-equivalent soil after 25 years under pasture in lowland Costa Rica. Others have found the reverse (Moraes et al., 1996; Neill et al., 1996). In studies of two 20-yr chronosequences at Fazenda Nova Vida, Rondônia, Moraes et al. (1996) found increases of 19% and 17% to a depth equivalent to 30 cm of forest soil [22% and 5%, respectively, if not corrected for clay content]. In two other 20-yr chronosequences in the same part of Rondônia, Moraes et al. (nd, cited by Moraes et al., 1995: 77) found an increase [of ___% in the top ___ cm] in one chronosequence and no significant change [in the top ___ cm] in the other. Another study of the layer equivalent to 30 cm of forest soil in the same area (M. Grzebyk, unpublished data cited by Moraes et al., 1996: 77) found a decrease of 5% in the carbon stock in 3-yr-old pasture, followed by increases of 5% in 9-yr-old pasture and 10% in 20-yr-old pasture. Neill et al. (1996) found an increase in soil carbon concentration to a depth of 30 cm in pastures five or more years old in very well-managed pasture at Fazenda Nova Vida, Rondônia. Some studies have found no significant change (Buschbacher, 1984; Choné et al., 1991; Kauffman et al., nd).

It is logical to expect that conversion of forests to pasture would decrease soil carbon stocks, as the temperature of the soil increases markedly when exposed to the sun in a pasture, a factor known to shift the equilibrium between formation and oxidation of organic carbon to a lower plateau (Cunningham, 1963; Greenland and Nye, 1959; see also Sánchez, 1976: 164-172). In addition, annual burning in tropical savannas is known to reduce raw organic matter additions to the soil (Sánchez, 1976: 170), and the same effect can be expected to apply to planted cattle pastures.

Conversion of forest to pasture reduces the water storage capacity of the soil (Chauvel et al., 1991) and confines the distribution of inputs of carbon from the roots to the surface layers (Nepstad et al., 1994). Both of these factors, together with high rates of decomposition (oxidation) of soil carbon (especially near the surface), could result in a decline in the soil carbon stock (Post et al., 1995).

There may be additional effects on the soil mesofauna. Termites (Isoptera), leaf-cutter ants (Atta spp.), cicadas (Cicadidae) and springtails (collembola) are important in incorporating litter and half-burned plant remains into the soil (at greater depth). These populations can be expected to be affected both by the transformation of forest to pasture and by the periodic impacts of fire. Termite populations take approximately six years to increase their populations in cleared areas in response to the increased availability of dead wood; termite populations then decline to low levels by the tenth year after deforestation as the dead wood in the original forest remains disappears through decomposition and burning (Martius et al., 1996). Leaf-cutter ant populations increase in pasture, especially degraded pasture with invading woody plants (the leaves of which the ants prefer over those of grasses); these ants carry substantial quantities of plant matter to their nests in the soil at depths sometimes exceeding 5 m (Nepstad et al., 1995a).

The sources of soil carbon can be identified using isotopic fractionation techniques. Forest trees fix 12C by the C3 photosynthetic pathway. The 13C isotope is produced by the C4 pathway (characteristic of pasture). The isotopic composition, expressed as d 13C (a measure of change in the ratio of 13C/12C relative to an international standard), allows the rates of supply and degradation to be estimated in pasture, even if no difference is apparent between forest and pasture carbon stocks based on carbon concentration and soil bulk density (e.g., Desjardins et al., 1994; Trumbore et al., 1995; Moraes et al., 1995; Neill et al., 1996). Changes in 14C accumulation from nuclear weapons testing also provides a means of obtaining statistically significant indicators of carbon turnover even when traditional carbon inventory measurements produce results too variable to detect differences with statistical significance (Trumbore et al., 1995).

When conversion of forest to pasture results in a new equilibrium with lower soil carbon stocks, the losses occur in small amounts over time (Davidson et al., 1993; Barbosa, 1994). These losses can occur due to incomplete substitution of the organic carbon source that had been provided by the forest. Although pasture provides a strong source of carbon to the soil, these inputs are not enough to compensate for losses of initial forest soil carbon (Desjardins et al., 1994: 113). This leads to a net loss of carbon from the ecosystem due to humification of the pasture roots (stock) not exceeding the emission from oxidation during and/or after burning. Repeated burning, change from a high- to a low-biomass system, trampling by hooves of the cattle, and exposure to rain and direct sunlight can cause small local effects that, under the most common management regime in Brazilian Amazonia, accumulate over the long term to transform the landscape from productive pasture into a degraded system and a net source of carbon to the atmosphere.

C.) EFFECTS OF PASTURE MANAGEMENT REGIMES

Over the long term, global calculations have shown losses of carbon stocks when forests are converted to other land uses. Detwiler (1986) and Detwiler and Hall (1988) suggested that the stock of soil carbon in a 40-cm profile in the tropics could be reduced by 20% by conversion of primary forest to pasture, and used this value in modeling the effects of deforestation on the global carbon budget. Lugo et al. (1986) and Houghton et al. (1987) assumed that the losses in converting land to pasture and agriculture, respectively, could reach 25% to a depth of 1 m. These are reviews derived from a variety of studies, and a wide range of values has been obtained by different authors. However, a study of the 0-30 cm layer in soils in Rondônia by Moraes et al. (1996) indicated that, over the long term, there is an increase in the stock of carbon in well-managed pasture as compared to nearby primary forest. In an extreme case, carbon in the top 20 cm of soil under very well-managed pasture in an agricultural station near Manaus returned to approximately the same level present under original forest eight years after clearing (90 t C/ha under forest versus 96 t C/ha under pasture, without correction for soil compaction), following a decline by 21.4% reached two years after clearing (Cerri et al., 1991; Choné et al., 1991). Teixeira (1987: 59) found a similar pattern for carbon content in well-managed pasture near Manaus. Under more commonly occurring conditions, the opposite result was found by Serrão and Falesi (1976) and by Eden et al. (1991); these authors found, respectively, a decline of about 50% in carbon concentration in pasture soil with 11 years of use in Fazenda Suiá Missu, Mato Grosso, and a 15% decline in concentration in pasture with 12 years of use near Maracá Island, Roraima. Fearnside (1978: 254) found mixed results: a gain in carbon concentration upon forest conversion that maintained its new level through 1-2 years of pasture, and carbon loss with conversion that only partially regained forest soil levels after 6-16 years of use. Well-managed pastures are not typical of Amazonia, and are unlikely to reflect regional means for the increase or decrease of carbon stocks caused by land use change (Trumbore et al., 1995).

The quality of management of tropical pastures is critical to the conclusions drawn about whether the soils under this land use represent a source or a sink of atmospheric carbon. In well-managed pastures in formerly forested areas, the root system of the pasture grass can redistribute carbon to deeper layers (Nepstad et al., 1991) where it is less susceptible to decomposition. This could be used as a strategy for carbon sequestration in soils in the areas that have already been coverted to pasture (Batjes and Sombroek, 1997). The same is true of well-managed pastures planted in former natural savanna areas (Fisher et al., 1994). However, this conclusion is wholly dependent on the pastures being very well managed, such as those on the agricultural experiment station in Colombia where the work on former savannas was carried out (see Nepstad et al., 1995b). Unfortunately, the vast majority of cattle pastures in Brazilian Amazonia is poorly managed: grass productivity declines within a decade, regardless of whether the pastures are on formerly forested or on former savanna land. Under typical (i.e. minimal input) management conditions at Ouro Preto do Oeste, Rondônia, measurements of grass productivity indicate that a 12-year-old pasture produces only about half as much above-ground dry weight of pasture grass annually as compared to a three-year-old pasture (Fearnside, 1989).

IV.) EFFECTS MASKING SOIL CARBON CHANGES

A.) FINE-SCALE SPATIAL VARIABILITY

Fine-scale spatial variability in soil properties, including carbon concentration, clay content and bulk density, could mean that the results of many studies that substitute space for time to compare soil samples taken at about the same time from a series (chronosequence) of pastures of different ages could produce the varied results that they do merely because of soil quality differences that have nothing to do with the effect of time under pasture. The presence of trees in the forests with which pasture soils are compared results in spatial variability in both carbon concentration and bulk density being significant over shorter distances in forest samples than pasture samples (Veldkamp and Weitz, 1994). Studies vary in the methodology used to collect the samples (ranging from point samples at a single pit or core to composite samples representing wider areas), making them correspondingly more or less subject to the effect of fine-scale spatial variation.

B.) CORRECTION FOR SOIL COMPACTION

Corrections applied (or not applied) by different authors to soil carbon measurements can make a substantial difference in the conclusions reached. Correction for the effect of soil compaction is needed for valid results. If one compares, for example, the top 20 cm of soil under pasture with the top 20 cm of soil under forest, it is possible to conclude that carbon has increased when, in reality, it has declined. This is because the soil in the top 20 cm under pasture has been compacted from a thicker layer under the forest, and the comparison of the stock of carbon (the concentration of carbon multiplied by the bulk density and the volume of soil) must be done between equivalent weights of soil in the two land uses. A growing number of soil carbon studies have made a correction for compaction since it was first introduced in 1985 (Fearnside, 1985), but studies without the correction (or without a clear explanation of what corrections have been applied) continue to contribute to confusion over the effect of deforestation on emissions from the soil. Measurements of soil bulk density are much less frequently made than are measurements of carbon concentration, perhaps because of the considerable additional work that density measurement adds to the demands of field sampling. Bulk density results are also subject to high variability, stemming from slight differences in methodology, for example among different investigators.

C.) CORRECTION FOR CLAY CONTENT

An additional correction was done by Moraes et al. (1996) for soil clay content, based on the finding of Feller et al. (1991) that soil organic matter is closely related to the clay content of the soil, such that the variation in clay content over fine spatial scales could mask the effect of land-use changes. This is consistent with what is known about the reaction of organic matter with iron and aluminum oxides. These oxides react with organic radicals to form complexes that remain relatively resistant to mineralization, possibly because the oxides may physically block access of microorganisms to the organic particles, thereby inhibiting their decomposition (Sánchez, 1976: 164).

Applying a correction for clay content is not easily done without masking the land-use change effects that need to be estimated for use in greenhouse gas emission calculations. The clay content correction by Moraes et al. (1996: 68) assumes that there is no change in the clay content of the soil resulting from land-use change. Moraes et al. (1996) calculate changes over 20 years, and Cerri et al. (1996) use these data to calculate changes over 35 years; both periods are sufficient for appreciable granulometric changes to occur. By correcting the measured carbon values in the pasture to reflect what the carbon values would be if clay were the same as that under undisturbed forest, one hides any change in soil carbon that may have resulted from deforestation's effect on soil clay content.

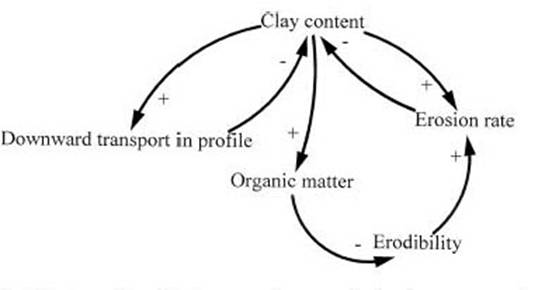

A decrease in clay content is one of the changes known to result from conversion of forest to pasture. This occurs by two mechanisms. First, soil erosion preferentially removes the smaller soil particles (i.e. clay), leaving the coarser particles (such as sand) behind (Lal, 1977: 54). Clay content is the most important determinant of erodability (the susceptibility of a soil to erosion), an effect only partially offset by a negative relationship between organic matter and erodability (Mitchell and Bubenzer, 1980: 32-33). Soil erosion on clay soils on the Transamazon Highway has been found to be more rapid than on sandy soils with the same slope and land use (Fearnside, 1980b, 1986b), and significant rates of soil erosion have been measured under cattle pasture (Barbosa, 1991; Fearnside, 1989). The second mechanism is the transport of clay particles downward in the soil profile, leaving the coarser particles at the surface (Scott, 1975, 1978). Removal of clay to the deeper layers would lead to a decline in the total carbon inventory, even though the transported clay remains in the soil column. This is because the deeper soil layers have lower rates of supply of organic carbon due to the lower density of roots in these soil layers. Relationships between clay content and soil carbon are summarized in Figure 2.

[Fig. 2 here]

The portion of the soil most affected by alteration of clay content is that closest to the surface, which is precisely where organic matter is most highly concentrated and dynamic. All of these clay content changes would tend to decrease the carbon stock under pasture soils, but this decrease would be hidden when a correction is applied for clay content between the forest and the pasture or between the pastures of different ages (as was done by Moraes et al., 1996). In the study by Moraes et al. (1996), the clay correction did not alter the direction of the change in carbon stock, but it did increase the estimated rise in carbon stock from 13.5%+8.5 to 18%+1.

It is possible that the values found for stocks and emissions of soil carbon depend more on the soil type (including clay content) than they do on the management system that replaces forest (e.g. Allen, 1985). Clayey soils tend to have more carbon per unit area (Cerri et al., 1992). This could lead to greater releases of carbon, as the amount of carbon lost is positively related to the amount initially present (Allen, 1985; Fearnside, 1986b: 194; Mann, 1986).

D.) HUMIFIED VERSUS NON-HUMIFIED MATERIAL

Nye and Greenland (1960: 70) pointed out that much confusion over the effects of burning on soil organic matter has been caused by failure to distinguish between humified and non-humified material. This confusion continues today both with regard to the effect of burning and with regard to the overall effect of forest-to-pasture conversion. At the time of burning, almost all litter present is combusted, but this is not humus or soil organic matter (which is little changed). The classification of roots as included or not in soil organic matter can have a dramatic effect on conclusions. In a recently implanted cattle pasture, the dead (but unhumified) coarse roots remaining from the original forest would appear as a tremendous jump in soil organic matter if this stock were considered to be part of the soil carbon pool. By the same token, the greater number of fine roots in the surface layers of pasture soil also would appear to be a huge increase in soil carbon if these roots were considered to be part of the soil rather than part of the biomass. Since soil analyses frequently define whatever passes through a 2 mm sieve as part of the soil, these fine roots can be an important component of reported increases in soil carbon as a result of conversion to pasture.

E.) SEASONAL CYCLES

A seasonal cycle of soil carbon stocks complicates assessment of the effects of conversion of forest to pasture. A persistent problem in interpreting published results on soil carbon changes with burning is that authors rarely report the dates of the pre- and post-burn samples, making it impossible to tell if the increases or decreases reported are due to the burning or to the normal seasonal cycle of soil carbon stocks.

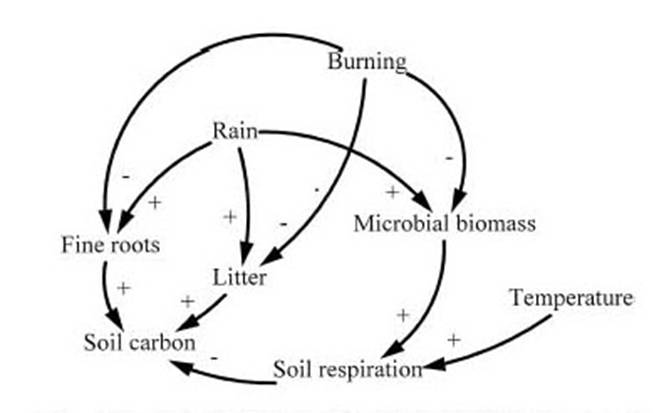

The content and composition of the soil organic matter can be influenced as a result of seasonal changes (Andreux et al., 1990), resulting in different phases of accumulation and loss of carbon in the soil under the system. The peak carbon stock in tropical soils that the few available data suggest occurs during the rainy season appears likely to be linked to the increase in volume of fine roots during this period in pastures. Measurements taken in an Oxisol near Manaus indicate that this component almost doubles in weight during the rainy season, as compared to the dry season, in a young Brachiaria humidicola pasture, especially in the 0-5 cm layer (Luizão et al., 1992). A similar result was found by Veldkamp (1993: 40) in fertile soils (Andisols and Inceptisols) in Costa Rica in B. dictyneura pasture. The seasonal cycle in soil carbon stocks results from the seasonality of carbon inputs, which are only partially offset by increases during the rainy season in microbial biomass (Luizão et al., 1992), and consequently also in soil respiration (Feigl et al., 1995). A seasonal cycle in soil carbon stocks is suggested by changes over time observed under pasture in Apiaú, Roraima (Barbosa, 1994). However, similar data from Fazenda Nova Vida, Rondônia fail to show a consistent seasonal pattern (P.M.L.A. Graça, unpublished data). The principal seasonal effects are diagrammed in Figure 3.

[Fig. 3 here]

Burning is a seasonal event, occurring only in the dry season; burning lowers microbial and fine root biomass and removes the litter that would otherwise decay and provide a source of carbon input to the soil. The seasonal cycle of rainfall produces parallel cycles of microbial biomass, fine roots and litter production. Any seasonal changes in temperature will be reflected in the rate of soil respiration.

V.) A BEST CURRENT ESTIMATE FOR AMAZONIA

Global calculations of greenhouse gas fluxes must, of necessity, include estimates for the net carbon release or uptake from soils, even if the value used is zero. The existence of uncertainty is not a valid rationale for failing to arrive at a best current estimate. Where, then, do we stand with respect to a best current estimate for the impact on soil carbon of the massive conversion of forest to pasture now underway in Brazilian Amazonia?

The available data require standardization for the treatment of bulk density effects and for the depth of sampling. Most important, the representativeness of the pasture management systems at the study sites must be taken into account, and an appropriate stratification by pasture management system must be applied to arrive at a best estimate for the region as a whole.

Studies are also varied in the age of pasture for which the effect is estimated (and in the validity of the assumption that a new equilibrium has been established by the year in question). The reliability of the methods used also varies among studies. Corrections are not attempted for these factors, but studies judged to be restricted to short-term effects, to reflect land-use effects other than pasture, or to be unreliable for any reason were eliminated from consideration.

Soil compaction, or bulk density increase, depends on the depth of the soil examined and the soil type. The current estimate standardizes depths for soil carbon in 0-20 cm, 20-100 cm and 100-800 cm layers. Soil compaction information is not standardized by layer, but rather only results of studies done on the 0-20 cm layer are used. Compaction is (optimistically) assumed to be zero below a depth of 20 cm.

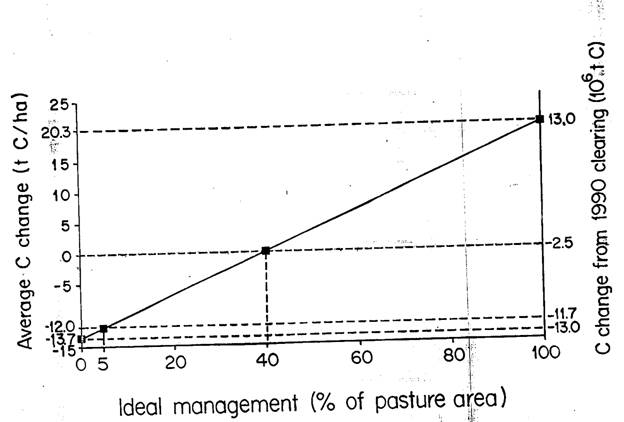

Bulk density changes from five studies are used to calculate a mean increase of 16% for the 0-20 cm layer (Table 1). Other measurements are also presented in Table 1, including measurements for other soil layers and measurements outside of Brazil (studies from Costa Rica's volcanic soils were not used in the calculations, although the results are very similar to those used here). One Brazilian study of the 0-20 cm layer (Hecht, 1981: 95) was not used in the calculations because the value reported for forest soil density (0.56 g/cm3) seems improbably low. The additional studies listed generally have higher values for bulk density increase than do those used in the calculations, giving added assurance that the values used do not exaggerate this effect.

[Table 1 here]

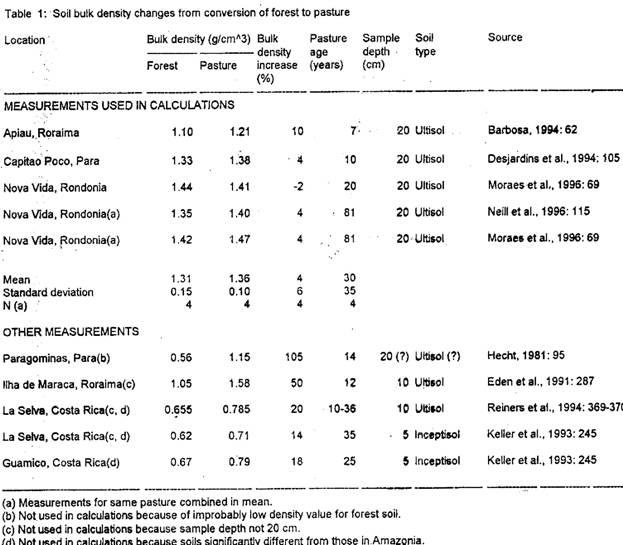

A number of studies of soil carbon changes have used soil depth ranges other than those adopted for the current estimate. Approximations for the stocks in the layers considered here can be made based on the relationships among stocks in different layers found by other workers (Table 2). The firmest relation is that between 0-20 cm and 1-100 cm derived by Moraes et al. (1995) based on over 1000 profiles collected throughout the region by the RADAMBRASIL project (Brazil, Projeto RADAMBRASIL, 1973-1983). Other conversions are based on many fewer studies, but variation in the proportional relationship among soil layers is small (Table 2).

[Table 2 here]

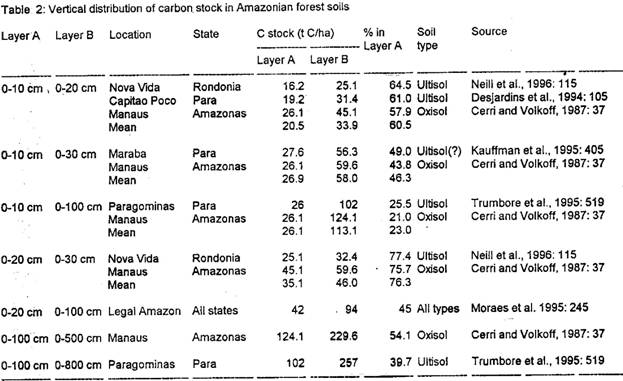

Studies of soil carbon stocks at different locations in Brazilian Amazonia and implied long-term changes from conversion to pasture are given in Table 3. These are separated into categories for "sites with typical management" (five studies) and "sites with ideal management" (five studies). Two of the studies in the first category and three in the second are for soil layers other than 0-20 cm. These are presented both with the original measurements and as values estimated from them for the 0-20 cm soil layer for the purposes of calculation. For consistency, the endpoint of each chronosequence was used to identify the carbon stock under pasture.

[Table 3 here]

Three of the studies that did not make a correction for compaction (Desjardins et al., 1994; Eden et al., 1991; Neill et al., 1996) included bulk density measurements that allow the correction to be performed here (Table 3). In one other study (Cerri et al., 1991) the average value from Table 1 (16% bulk density increase) is used. In this case (Cerri et al., 1991), application of the correction for bulk density reverses the sign of the carbon change, making the soil a net source rather than a net sink of carbon.

The 16% average compaction value from Table 1 is also used in re-intepreting the two measurements by Falesi (1976). Falesi's (1976) values indicate the greatest carbon losses. The data from this study had been used in a previous estimate of soil carbon loss from conversion of Amazonian forest to pasture (Fearnside, 1985, 1997b) but the compaction correction applied in that estimate may have been exaggerated because the forest soil density used (from Hecht, 1981: 95) has an unusually low value. Because the 0-20 cm layer under forest is believed to have greater mass than calculated previously, the results here indicate a higher average carbon release than the average computed earlier (3.92 t C/ha release from the 0-20 cm layer).

The carbon stocks under forest in the studies listed in Table 3 differ substantially from the 42 t C/ha average stock for the Legal Amazon region calculated by Moraes et al. (1995) for the 0-20 cm layer of soil. The five sites with "typical management" average only 26.5 t C, while the five studies with "ideal management" are also all lower than 42 t C/ha with the exception of one high value (90 t C/ha) found by Cerri et al. (1991: 254). This difference is handled by using the percentage changes in soil carbon in the 0-20 cm layer indicated by the studies in each management category, and applying these percentages to the regional average soil carbon stock as estimated by Moraes et al. (1995).

The suite of existing studies of soil carbon under pasture is highly unrepresentative of pastures in Brazilian Amazonia as a whole. A disproportionately large number of studies have been done in optimally managed pastures either in agricultural experiment stations or in the few ranches that make significant investments in inputs and pasture management (this minority of ranches is more likely to encourage research groups to study their pastures than is the majority that applies minimal management).

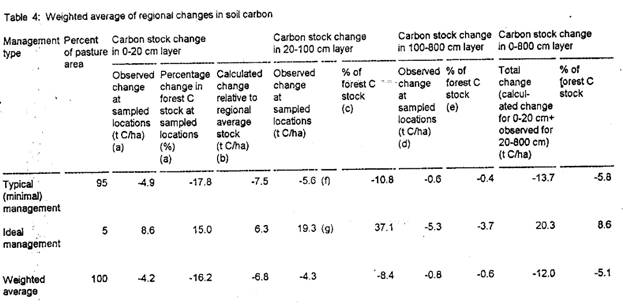

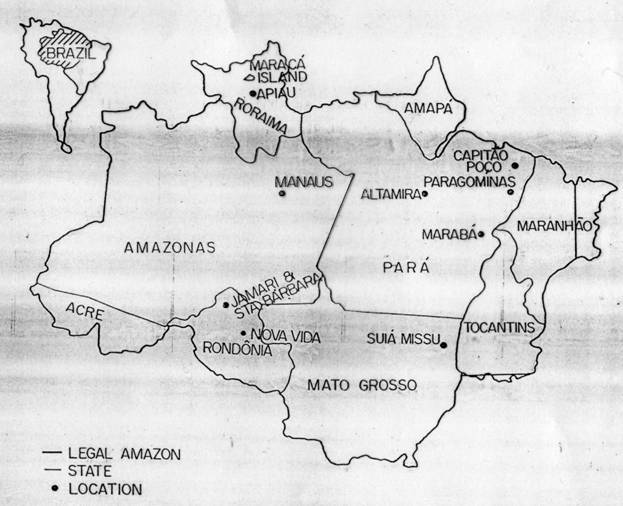

No estimate exists of the percentage of pasture land in Brazilian Amazonia that is managed under the ideal regimes in use at the study sites of a number of the available measurements of soil carbon changes under pasture. While the area under such management would have been close to zero (certainly well under 1% of the total pasture area) in the 1970s and 1980s, the financial returns to this kind of ranching improved in the 1990s (Mattos and Uhl, 1994; Arima and Uhl, nd). However, the overwhelming preponderance of pasture with minimal investment in management is still evident. Here the assumption will be made that 5% of the pastures in the region were under improved management regimes in 1990. Based on this assumption, weighted average of regional changes in soil carbon are computed (Table 4). Over the full 8-m soil profile, an average of 11.1 t C/ha is released, over half of this coming from the top 20 cm of soil.

[Table 4 here]

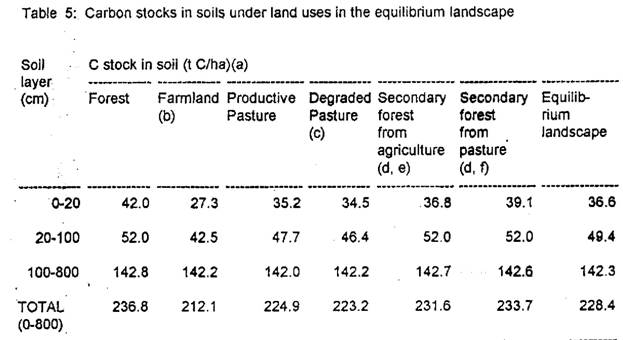

Approximate magnitudes and potential total soil carbon releases are computed for the 0.604 X 106 ha area of forest cleared in 1990 that will be maintained under actively managed (productive) pasture in the equilibrium landscape, for the 175.2 X 106 ha area that would be under pasture were all of the original forest in the Legal Amazon converted to the equilibrium landscape, and for the 400 X 106 ha originally forested area if all converted to pasture (Table 5).

[Table 5 here]

Low values for carbon loss are indicated for the 100-800 cm layer. However, complacency about the security of this pool is not recommended: the large size of the carbon pool in this soil layer means that even small changes (near detection limits) could have substantial impact on carbon emissions (see Trumbore et al., 1995; Nepstad et al., 1994). The slower dynamics of carbon in these deep layer, as compared to the surface layers, means that the pasture area in Amazonia will continue to release deep soil carbon for many years until a new equilibrium is reached; these additional emissions are not reflected in the results computed here.

The values for total carbon release from soils calculated here are not exactly the same as net committed emissions (see Table 5: note b). Net committed emissions would be substantially greater, especially for the large carbon pool in the deep soil.

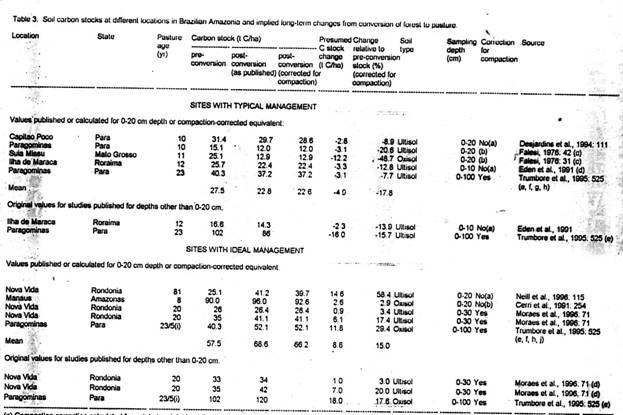

The percentage of Amazonian pastures where mangagement practices are similar to those where the studies in the "ideal management" category were carried out is critical to the overall effect of the region's pasture soils on carbon emissions (Figure 4). If none of the pastures in the region were in the "ideal" category, average carbon release from 8-m soil profile would be 13.3 t C/ha, or 8.1 X 106 t C from the portion of the area felled in 1990 that will eventually become actively-managed (productive) pasture in the equilibrium landscape. Were all of the pastures kept under ideal management, the soil C stock would increase by 30.9 t C/ha, or 18.7 X 106 t C for 1990. Considering 5% as a reasonable value for the percentage of the pastures under ideal management in 1990, average release of soil carbon would be 11.1 t C/ha of pasture, or 6.7 X 106 t C for 1990. If 0-10% is taken as a reasonable range for the percentage of pastures under ideal management, the lower bound would be a source of 8.9 t C/ha or 5.4 X 106 t C for 1990. An improbably high 30% would have to be under ideal management in order to turn pasture soils from a net source to a net sink of carbon.

[Fig. 4 here]

The 6.7 X 106 t C emission from soil carbon for pastures in the 1990 clearing represents an emission equivalent to over 10% of Brazil's emissions from fossil fuels. The net committed emission of carbon in 1990 from Amazonian deforestation sources other than soil totaled 257.0 X 106 t C, without considering trace-gas effects and excluding clearing of savannas such as cerrado (Fearnside, 1997b: 351). Considering (conservatively) the soil emission computed here as a net committed emission, this brings the total from Amazonian deforestation that year to 263.7 X 106 t C. Carbon from cerrado biomass would add approximately 8.6 X 106 t C (Fearnside, 1997b: 351). Ignoring any carbon changes in cerrado soils converted to pasture and agriculture (primarily soybeans), the 1990 total emission from land use change in Brazil's 5 X 106 km2 Legal Amazon region was 272.3 X 106 t C, of which soils represent 2.5%.

VI.) CONCLUSIONS

The literature indicates a mixture of findings for soil carbon stocks ranging from increases to decreases as a result of conversion of forest to pasture. Some of the varied results can be explained by correction (or lack of correction) for factors such as soil compaction and clay content, and the effect of the short-term seasonal cycles. Factors like sampling depth, number of samples, soil type, dominant vegetation and the quantity and type of carbon previously present are of fundamental importance to calculating mean values for use in simulations of carbon emissions and uptakes. The need is evident for longitudinal studies monitoring soil carbon stocks and related parameters in long-term plots established in areas converted from forest to pasture. Whether pasture soils are a net sink or a net source of carbon depends on their management, but an approximation of the fraction of pastures under "typical" and "ideal" management practices indicates that pasture soils in Brazilian Amazonia are a net carbon source, with an average release of 11.1 t C/ha, or 6.7 X 106 t C for pastures from forest felled in 1990. Although this represents only 2.5% of the impact of 1990 deforestation (biomass + pasture soil emissions), it represents a carbon release equivalent to over 10% of Brazil's annual emission from fossil fuels.

VII.) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thierry Desjardins, Wim G. Sombroek and Paulo Maurício Lima de Alencastro Graça for comments on the manuscript.

VIII.) LITERATURE CITED

Allen, J.C. (1985). Soil response to forest clearing in the United States and the tropics: Geological and biological factors. Biotropica 17(1): 15-27.

Andreux, F.G.; Cerri, C.C.; Eduardo, B.P. and Choné, T. (1990). Humus contents and transformations in native and cultivated soils. The Science of the Total Environment 90: 249-265.

Arima, E.Y. and Uhl, C. (nd.).

Ranching in the Brazilian Amazon in a national context: Economics, policy, and practice. Society and Natural Resources (in press).

Barbosa, R.I. (1991). Erosão do solo na Colônia do Apiaú, Roraima, Brasil: Dados preliminares. Boletim do Museu Integrado de Roraima

1(2): 22-40.

Barbosa, R.I. (1994). Efeito Estufa na Amazônia: Estimativa da Biomassa e a Quantificação do Estoque e Liberação de Carbono na Queima de Pastagens Convertidas de Florestas Tropicais em Roraima, Brasil. Masters thesis in ecology. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA) & Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. 85 pp.

Barbosa, R.I. and Fearnside, P.M. (1996). Pasture burning in Amazonia: Dynamics of residual biomass and the storage and release of aboveground carbon. Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres) 101(D20): 25,847-25,857.

Batjes, N.H. and Sombroek, W.G. (1997).

Possibilities for carbon sequestration in tropical and subtropical soils. Global Change Biology 3: 161-173.

Brazil, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas

Espaciais (INPE) (1996). Levantamento

das Áreas Desflorestadas na Amazônia Legal no Período 1991-1994: Resultados.

INPE, São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil. 9 pp.

Brazil, Projeto RADAMBRASIL. (1973-1983). Levantamento

de Recursos Naturais, Vols. 1-23. Ministério das Minas e Energia,

Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral (DNPM) Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Brown, S. and Lugo, A.E. (1982). The storage and production of organic matter in tropical forests and their role in the global carbon cycle. Biotropica 14(2): 161-187.

Buschbacher, R.J. (1984). Changes in Productivity and Nutrient Cycling Following Conversion of Amazon Rainforest to Pasture. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, U.S.A. xiii + 193 pp.

Cerri, C.C.; Moraes, J.F.L. and Volkoff, B. (1992). Dinâmica do carbono orgânico em solos vinculados a pastagens na Amazônia. Rev. INIA Invest. Agr. 1(1): 95-102.

Cerri, C.C. and Volkoff, B. (1987). Carbon content in a yellow latosol of Central Amazon rain forest. Acta OEcologica 8(1): 29-42.

Cerri, C.C.; Volkoff, B. and Andreux, F. (1991). Nature and behaviour of organic matter in soils under natural forest, and after deforestation, burning and cultivation, near Manaus. Forest Ecology and Management 38: 247-257.

Cerri, C.C.; Volkoff, B. and

Eduardo, B.P. (1985). Efeito

do desmatamento sobre a biomassa microbiana em latossolo amarelo da

Amazônia. Revista Brasileira de

Ciência do Solo 9(1): 1-4.

Cerri, C.C.; Bernoux, M. and Feigl, B.J. (1996). Deforestation and use of soil as pasture: Climatic impacts. pp. 177-186 In: R. Lieberei, C. Reisdorff and A.D. Machado (eds.) Interdisciplinary Research on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of the Amazonian Rain Forest and its Information Requirements. Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH (GKSS), Bremen, Germany. 323 pp.

Chauvel, A.; Grimaldi, M. and Tessier, D. (1991). Changes in pore-space distribution following deforestation and revegetation: An example from the Central Amazon Basin, Brazil. Forest Ecology and Management 38: 247-257.

Choné, T.; Andreux, F.; Correa, J.C.; Volkoff, B. and Cerri, C.C. (1991). Changes in organic matter in an oxisol from the Central Amazonian forest during eight years as pasture, determined by 13C isotopic composition. pp. 397-405 In: J. Berthelin (ed.) Diversity of Environmental Biogeochemistry. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. ____ pp.

Cunningham, R.H. (1963). The effect of clearing a tropical forest soil. Journal of Soil Science 14: 334-344.

Davidson, E.A.; Nepstad, D.C. and Trumbore, S.E. (1993). Soil carbon dynamics in pastures and forests of the eastern Amazon. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 74(2) supplement: 208 (Abstract).

Desjardins, T.; Andreux, F.; Volkoff, B. and Cerri, C.C. (1994). Organic carbon and 13C contents in soils and soil size-fractions, and their changes due to deforestation and pasture installation in Eastern Amazonia. Geoderma 61: 103-118.

Detwiler, R.P. (1986). Land use change and the global carbon cycle: the role of the tropical soils. Biogeochemistry 2: 67-93.

Detwiler, R.P. and Hall, C.A.S. (1988). Tropical forests and the global carbon cycle. Science 239: 42-47.

Eden, M.J.; Furley, P.A.;

McGregor, D.F.M.; Milliken, W. and Ratter, J.A. (1991). Effect of forest clearance and burning on

soil properties in northern Roraima, Brazil.

Forest Ecology and

Management 38:

283-290.

Falesi, I.C. (1976). Ecossistema de Pastagem Cultivada na Amazônia Brasileira. (Boletim Técnico No. 1). Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária/Centro de Pesquisas Agro-Pecuárias do Trópico Úmido (EMBRAPA/CPATU), Belém, Pará, Brazil. 193 pp.

Fearnside, P.M. (1978). Estimation of Carrying Capacity for Human Populations in a part of the Transamazon Highway Colonization Area of Brazil. Ph.D. dissertation in biological sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. 624 pp.

Fearnside, P.M. (1980a). The effects of cattle pasture on soil fertility in the Brazilian Amazon: Consequences for beef production sustainability. Tropical Ecology 21(1): 125‑137.

Fearnside, P.M. (1980b). The prediction of soil erosion losses under various land uses in the Transamazon Highway colonization area of Brazil. pp. 1287‑1295 In: J.I. Furtado (ed.) Tropical Ecology and Development: Proceedings of the Vth International Symposium of Tropical Ecology, 16‑21 April 1979, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. International Society of Tropical Ecology (ISTE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 1383 pp.

Fearnside, P.M. (1985). Brazil's Amazon forest and the global carbon problem. Interciencia 10(4): 179-186.

Fearnside, P.M. (1986a). Brazil's Amazon forest and the global carbon problem: Reply to Lugo and Brown. Interciencia 11(2): 58‑64.

Fearnside, P.M. (1986b). Human Carrying Capacity of the Brazilian Rainforest. Columbia University Press, New York, U.S.A. 293 pp.

Fearnside, P.M. (1989). Ocupação Humana de Rondônia: Impactos, Limites e Planejamento. Relatórios de Pesquisa No. 5. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brasília, Brazil. 76 pp.

Fearnside, P.M. (1996). Amazon deforestation and global warming:

Carbon stocks in vegetation replacing Brazil's Amazon forest. Forest Ecology and Management 80: 21-34.

Fearnside, P.M. (1997a). Amazonie: La déforestation repart de plus belle. La destruction de la forêt dépend étroitemente des choix politiques. La Recherche No. 294: 44-46.

Fearnside, P.M. (1997b). Greenhouse gases from deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: Net committed emissions. Climatic Change 35(3): 321-360.

Fearnside, P.M.; Leal Filho, N. and Fernandes, F.M. (1993). Rainforest burning and the global carbon budget: Biomass, combustion efficiency and charcoal formation in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres) 98(D9): 16,733-16,743.

Feigl, B.J.; Steudler, P.A. and Cerri, C.C. (1995). Effects of pasture introduction on soil CO2 emissions during the dry season in the state of Rondônia, Brazil. Biogeochemistry 31: 1-14.

Feller, C.; Fritsch, E.; Poss, R.

and Valentin,C. (1991). Effet de la

texture sur le stockage et la dynamique des matières organiques dans quelques

sols ferugineux et ferralitiques (Afrique de l'Ouest, en particuler). Cahiers

ORSTOM, Série Pédologie. 26: 25-36.

Fisher, M.J.; Rao, I.M.; Ayarza, M.A.; Lascano, C.E.; Sanz, J.I.; Thomas, R.J. and Vera, R.R. (1994). Carbon storage by introduced deep-rooted grasses in South American savannas. Nature 371: 236-238.

Greenland, D.J. and Nye, P.H.

(1959). Increases in the carbon and

nitrogen contents of tropical soils under natural fallows. Journal of Soil Science 10: 284‑299.

Guimarães, W.M. (1993). Liberação de Carbono e Mudanças nos Estoques de Nutrientes Contidos na Biomassa Aérea e no Solo, Resultante de Queimadas de Florestas Secundárias em Áreas de Pastagens Abandonadas, em Altamira, Pará. Master's thesis. Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia/Fundação Universidade do Amazonas (INPA/FUA), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. 69 pp.

Hecht, S.B. (1981). Deforestation in the Amazon Basin: Magnitude, dynamics and soil resource effects. Studies in Third World Societies 13: 61-108.

Hecht, S.B. (1982). Cattle Ranching Development in the Eastern Amazon: Evaluation of a Development Policy. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. 454 pp.

Houghton, R.A.; Boone, R.D.; Fruci, J.R.; Hobbie, J.E.; Melillo, J.M.; Palm, C.A.; Peterson, B.J.; Shaver, G.R. and Woodwell, G.M. (1987). The flux of carbon from terrestrial ecosystems to the atmosphere in 1980 due to changes in land use: Geographic distribution of the global flux. Tellus 1-2: 122-139.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Joint Programme. (1994). Greenhouse Gas Inventory. OECD, Paris, France. 3 vols.

Kauffman, J.B.; Cummings, D.L.; Ward, D.E. and Babbitt, R. (1995). Fire in the Brazilian Amazon. 1. Biomass, nutrient pools, and losses in slashed primary forests. Oecologia 104: 397-408.

Kauffman, J.B.; Cummings, D.L.; Ward, D.E. and Babbitt, R. (nd). Fire in the Brazilian Amazon: 2. Biomass, nutrient pools and losses in cattle pastures. (manuscript).

Keller, M.; Kaplan, W.A. and Wofsy, S.C. (1986). Emissions of N2O, CH4 and CO2 from tropical forest soils. Journal of Geophysical Research (Atmospheres) 91(D11): 11,791-11,802.

Keller, M.; Veldkamp, E.; Weltz, A.M. and Reiners, W.A. (1993). Effect of pasture age on soil trace-gas emissions from a deforested area of Costa Rica. Nature 365: 244-246.

Lal, R. (1977). Analysis of factors affecting rainfall erosivity and soil erodibility. pp. 49-56 In: D.J. Greenland and R. Lal (eds.) Soil Conservation and Management in the Humid Tropics. Wiley, New York, U.S.A. 283 pp.

Laudelot, H. (1961). Dynamics of Tropical Soils in Relation to their Fallowing Techniques. Paper 11266/E. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, Italy. 111 pp.

Lugo, A.E.; Sanchez, M.J. and Brown, S. (1986). Land use and organic carbon content of some subtropical soils. Plant and Soil 96: 185-196.

Luizão, F.; Luizão, R. and

Chauvel, A. (1992). Premiers résultats sur la dynamique des biomasses

racinaires et microbiennes dans un latosol d'Amazonie centrale (Brésil) sous

forêt et sous páturage. Cahiers Orstom - Pédologie 27(1): 69-79.

Mann, L.K. (1986). Changes in soil carbon storage after cultivation. Soil Science 142(5): 279-288.

Martins, P.F.S.; Cerri, C.C.; Volkoff, B. and Andreux, F. (1990). Efeito do desmatamento e o cultivo

sobre características físicas e químicas do solo sob floresta natural na

Amazônia oriental. Revista IG

(São Paulo) 11(1): 21-33.

Martius, C.; Fearnside, P.M.; Bandeira, A.G. and Wassmann, R. (1996). Deforestation and methane release from termites in Amazonia. Chemosphere 33(3): 517-536.

Mattos, M.M. and Uhl, C. (1994). Economic and ecological perspectives on ranching in the Eastern Amazon. World Development 22(2): 145-158.

Mitchell, J.K. and Bubenzer, G.D. (1980). Soil loss estimation. pp. 17-62 In: M.J. Kirkby and R.P.C. Morgan (eds.) Soil Erosion. Wiley, New York, U.S.A. 312 pp.

Moraes, J.F.L. (1991). Conteúdos de Carbono e Nitrogênio e Tipologia de Horizontes nos Solos da

Bacia Amazônica.

Master's thesis. Centro de Energia Nuclear na Agricultura/Universidade de São

Paulo (CENA/USP), Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil. 84 pp.

Moraes, J.L.; Cerri, C.C.; Melillo, J.M.; Kicklighter, D.; Neil, C.; Skole, D.L. and Steudler, P.A. (1995). Soil carbon stocks of the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Soil Science Society of America Journal 59: 244-247.

Moraes, J.F.L. de; Volkoff, B.; Cerri, C.C. and Bernoux, M. (1996). Soil properties under Amazon forest and changes due to pasture installation in Rondônia, Brazil. Geoderma 70: 63-81.

Moraes, J.F.L. de; Neill, C.; Volkoff, B.; Cerri, C.C.; Melillo, J.; Lima, V.C. and Steudler, P.A. (nd.). Soil carbon and nitrogen stocks following conversion to pasture in the western Brazilian Amazon Basin. (manuscript).

Neill, C.; Fry, B.; Melillo, J.M.; Steudler, P.A.; Moraes, J.F.L. and Cerri, C.C. (1996). Forest- and pasture-derived carbon contributions to carbon stocks and microbial respiration of tropical pasture soils. Oecologia 107: 113-119.

Nepstad, D.C.; Carvalho, C.R.;

Davidson, E.A.; Jipp, P.H.; Lefebvre, P.A.; Negreiros, G.H.; Silva, E.D.;

Stone, T.A.; Trumbore, S.E. and Vieira, S. (1994). The role of deep roots in

the hydrological cycles of Amazonian forests and pastures. Nature 372:

666-669.

Nepstad, D.C.; Jipp, P.; Moutinho, P.; Negreiros, G. and Vieira, S. (1995a). Forest recovery following pasture abandonment in Amazonia: Canopy seasonality, fire resistance and ants. pp. 333-349 In: D.J. Rapport, C.L. Gaudet and P. Calow (eds.) Evaluating and Monitoring the Health of Large-Scale Ecosystems. NATO ASI Series Vol. 128. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. ____ pp.

Nepstad, D.C.; Klink, C. and Trumbore, S.E. (1995b). Pasture soils as carbon sink. Nature 376: 472-473.

Nepstad, D.C.; Uhl, C. and Serrão, E.A.S. (1991). Recuperation of a degraded Amazonian landscape: Forest recovery and agricultural restoration. Ambio 20: 248-255.

Nye, P.H. and Greenland, D.J. (1960). The Soil under Shifting Cultivation. Technical Communication No. 51. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux of Soils, Harpenden, U.K. 156 pp.

Post, M.W.; Anderson, D.W.; Dahmke, A.; Houghton, R.A.; Huc, A.Y.; Lassiter, R.; Majjar, R.G.; Meue, H-V.; Pedersen, T.F.; Trumbore, S.E. and Vaikmae, R. (1995). Group report: What is the role of nonliving organic matter cycling on the global scale? pp. 155-174 In: R.G. Zepp and C.H. Sontag (eds.) Role of Nonliving Organic Matter in the Earth's Carbon Cycle. Wiley, New York, U.S.A. ____pp.

Post, M.W.; Emanuel, W.R.; Zinke, P.J. and Stangerberger, A.G. (1982). Soil carbon pools and world life zones. Nature 298: 156-159.

Sánchez, P.A. 1976. Properties and Management of Soils in the Tropics. Wiley, New York, U.S.A. 618 pp.

Sánchez, P.A.; Villachica, J.H. and Bandy, D.E. (1983). Soil fertility dynamics after clearing a tropical rainforest in Peru. Soil Science Society of America Journal 47(6): 1171-1178.

Scott, G.A.J. (1975). Soil profile changes resulting from the conversion of forest to grassland in the Montaña of Peru. Great Plains‑Rocky Mountain Geographical Journal 4: 124‑130.

Scott, G.A.J. (1978). Grassland Development in the Gran Pajonal of Eastern Peru: a Study of Soil‑Vegetation Nutrient Systems. (Hawaii Monographs in Geography No. 1). University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. 187 pp.

Sombroek, W.G.; Nachtergaele, F.

and Hebel, A. (1993). Amounts, dynamics and sequestering of carbon in tropical

and subtropical soils. Ambio 22(7): 417-426.

Serrão, E.A.S. and Falesi, I.C. (1977). Pastagens do Trópico Úmido Brasileiro.

Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária/ Centro de Pesquisas Agro-Pecuárias

do Trópico Úmido (EMBRAPA/CPATU), Belém, Pará, Brazil. 63 pp.

Suares de Castro, F. (1957). Las quemas como

prática agricola y sus efectos. Federación Nacional Cafetaleros de

Colombia Boletin Técnico. 2.

Teixeira, L.B. (1987). Dinâmica do Ecossistema de Pastagem Cultivada em Área de Floresta na Amazônia Central. Ph.D. dissertation in ecology, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA) & Fundação Universidade do Amazonas (FUA), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. 100 pp.

Townsend, A.R.; Vitousek, P.M. and Holland, E.A. (1992). Tropical soils could dominate the short-term carbon cycle feedbacks to increase global temperatures. Climatic Change 22: 293-303.

Trumbore, S.E.; Davidson, E.A.; Camargo, P.B.; Nepstad, D.C. and Martinelli, L.A. (1995). Below-ground cycling of carbon in forests and pastures of eastern Amazonia. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 9(4): 515-528.

Uhl, C., Buschbacher, R. and Serrão, E.A.S. (1988). Abandoned pastures in Eastern Amazonia. I. Patterns of plant succession. Journal of Ecology 76: 663-681.

Uhl, C. and Jordan, C.F. (1984). Succession and nutrient dynamics following forest cutting and burning in Amazonia. Ecology 65(5): 1476-1490.

Uhl, C. and Kauffman, J.B. (1990). Deforestation, fire susceptibility, and potential tree responses to fire in the Eastern Amazon. Ecology 71: 437-449.

Veldkamp, E. (1993). Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics in Pastures Established after Deforestation in the Humid Tropics of Costa Rica. Ph.D. dissertation, Agricultural University of Wageningen, Wageningen, The Netherlands. 117 pp.

Veldkamp, E. (1994). Organic carbon turnover in 3 tropical soils under pasture after deforestation. Soil Science Society of America Journal 58: 175-180.

Veldkamp, E. and Weitz, A.M. (1994). Uncertainty analysis of d13 C method in soil organic matter studies. Studies in Biology and Biochemistry 26(6) 153-160.

Zinke, P.J.; Sabhasri, S. and Kunstadter, P. (1978). Soil fertility aspects of the Lua' forest fallow system of shifting cultivation. pp. 134-159 In: P. Kunstadter, E.C. Chapman and S. Sabhasri (eds.) Farmers in the Forest: Economic Development and Marginal Agriculture in Northern Thailand. East-West Center, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S.A. 402 pp.

FIGURE LEGENDS

Figure 1 -- Brazil's Legal Amazon region and locations mentioned in the text.

Figure 2 -- Relationships between clay content changes and soil carbon. The sign by each arrow represents the direction of change in the quantity at the head of the arrow given an increase in the quantity at the tail of the arrow.

Figure 3 -- Principal seasonal effects on soil carbon stocks.

Figure 4 -- Relation of soil carbon stock changes to the percentage of the actively managed pasture area that is under ideal management. The percentage is believed to be about 5%; an improbably high 30% would have to be under ideal management to turn pasture soils from a net source to a net sink of carbon.

Fig-1

Fig-2

Fig-3

Fig-4