The

text that follows is a PREPRINT.

Please cite as:

ISSN:

0378-1127

Copyright:

Elsevier

The original publication is available at: http://www.elsevier.com.nl

Fire

frequency and area burned in the Roraima savannas of Brazilian Amazonia

Reinaldo

Imbrozio Barbosa

INPA/CPEC

(Roraima)

C.P.

96

69301-970

Boa Vista, Roraima

Brazil

+55-(95)-623 9433

Philip Martin Fearnside

INPA/CPEC

C.P.

478

69011-970

Manaus, Amazonas

Brazil

+55-(92)-643 1822

1 July 2004

Abstract

Estimates were made of

the percentage of area burned and the fire frequency in different ecosystems of

non-anthropic savannas located in the north and northeast portions of the State

of Roraima, Brazil. Three years of observations (June 1997 to May 2000)

indicated that the mean percentage of area burned annually, weighted for all

ecosystems, was 38 ± 12 (SD) %. The mean frequency of fire (number of years for

an area to burn again) was 2.5 years. Both parameters are dependent on the type

(structure) of vegetation, the altitude of the savanna and the climatic state

(dry, wet or normal) of the year of the observation. Using values for two-month

periods over the three year time series (n=18), a simple regression model to

forecast percentage area burned was developed for Sg savannas (grassy-woody

savanna; “clean field” and “dirty field” types), using as the independent

variable the daily mean precipitation. The proposed model explains 66% of the

reported cases. These results are the first developed for savannas in the

Amazon region and are directly applicable to calculations of greenhouse-gas

emissions from burning in this ecosystem type.

Keywords: Amazonia;

Burned area; Fire frequency; Roraima; Savannas

1. Introduction

Amazonia plays an

important role in the maintenance of the world carbon balance (Fearnside, 1997;

Houghton et al., 2001; Nascimento and Laurance, 2002). Amazonia’s carbon

storage potential gives great importance to land-use changes in this region

because disturbances of the natural landscape can increase atmospheric carbon

and affect global biogeochemical cycles (Seiler and Crutzen, 1980; Houghton et

al., 1983; Greenberg et al., 1984; Crutzen and Andreae, 1990; Houghton, 1990;

Setzer and Pereira, 1991; Fearnside, 1996).

Biomass burning produces significant amounts of trace gases, such as

methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N20), which contribute

to global warming and other global atmospheric changes. Net emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2)

can also be affected.

Forest ecosystems

receive the attention of most of the scientific studies conducted in Amazonia

because forests represent the largest landscape in the region. However,

Amazonian savannas represent a significant portion of the area of terrestrial

systems, and, in the same way as the forests, savannas are rapidly being

converted for agriculture and ranching and is exposed to recurrent burning in

thousands of km2 of the remaining original (non-anthropic)

ecosystems. This transforms the savanna ecosystems into an important

terrestrial source of greenhouse gases (Seiler and Crutzen, 1980; Ward et al.,

1992; McNaughton et al., 1998; Hoffa et al., 1999).

Of the studies that

have been done on a large scale in Brazil on emission of gases by savannas,

most are limited to evaluations of the savannas of the country’s center-west

region, close to the area known as the “Arc of Deforestation” (Barbosa, 2001).

Of these, only two studies (Schroeder and Winjum, 1995; Fearnside, 1997) attempted to estimate the potential emission

of this Brazilian ecosystem despite the high uncertainty or outright lack of

values for some of the parameters needed for the calculations, such as the

extent of the area burned annually and the frequency of the passage of the

fire. These two factors are important in calculations of the storage and

release of carbon in savanna areas (IPCC/OECD, 1994).

Acceleration of burning

frequency can result in depletion of carbon and nitrogen stocks in the soil,

eventually leading to reduced grass productivity (Kauffman et al., 1994;

Scholes and Walker, 1993 cited by Sampson et al., 2000, p. 207). Burn frequency has increased in the cerrado

areas of Brazil’s center-west region as a result of more intense management of

these ecosystems for cattle grazing (Coutinho, 1990, pp. 87-88). Climatic changes such as increased frequency

of El Niño events, leading to dry years in Amazonia, could contribute to future

increases in burning frequency.

Due to the almost complete lack of

studies on this subject, most calculations of greenhouse-gas emissions use

unreferenced values (probably guesses) for fire frequency (e.g., Hao et al., 1990), or site a source that leads to one of

these unreferenced values. The values

put forward by Hao et al. (1990), for example, are used in subsequent estimates

(e.g., Scholes and Andreae, 2000) and

as IPCC default values (IPCC, 1996, p. 4.64).

Remote sensing is used to overcome the inherent deficiencies in this

type of calculation. However, the interpretation difficulties associated with

this method are also large because burn scars in savannas are visible for only

a short period (in contrast to burning associated with deforestation),

hindering measurement through remote sensing. It is possible to count the

number of fires (“hot pixels”), but not to estimate the size of the burned area

without an excessive amount of error (Kaufman et al., 1990; Robinson,

1991). Progress has been made in

perfecting sampling methods using the AVHRR sensor with verification of the

precision through LANDSAT-TM and/or SPOT images for determining burned areas in

central-African savannas (Barbosa et al., 1998; Barbosa et al., 1999a; 1999b;

Pereira et al., 1999) and in Brazilian cerrados (Brazil, MCT, 2002 citing Krug

et al., 2001; see also Krug and dos Santos, 2001). However, especially in the case of the

studies used in Brazil’s preliminary inventory of greenhouse gases (Brazil,

MCT, 2002), the number of LANDSAT images associated with the “hot spot” (fire

pixel) data from the AVHRR sensor was

insuficient to estimate area and frequency of burning in the non-anthropic Brazilian

cerrados without an excessive amount of uncertainty. An estimate for a small area of cerrado has

recently been done using LANDSAT imagery by itself, but without a means of

extending the estimate to the cerrado area as a whole (Krug et al., 2004).

The present study has

the objective of estimating the percentage of burned area and the frequency of

burning in non-anthropic Amazonian savannas through on-the-ground sampling

using the primary and secondary highways that cut through the largest block of

continuous savannas of the Brazilian Amazon, located in the State of Roraima.

The study covered “original” ecosystems (non-anthropic remnants), “anthropic”

ecosystems (agriculture and ranching) and “other ecosystems” that are

intermingled with the local savannas (e.g.,

forest islands).

2. Study

area

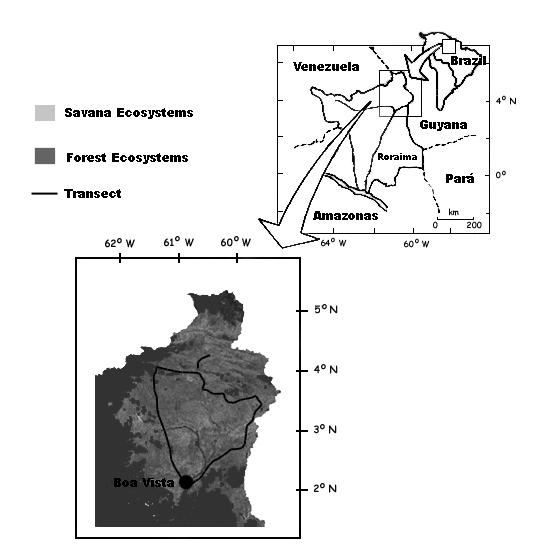

The study area is

located in the north-northeast area of the State of Roraima, in the

northernmost portion of the Brazilian Amazon – approximately between 2o

30' N and 5o 0' N and 59o 30' W and 61o 30' W

(Figure 1). This landscape is an enormous mosaic of savanna ecosystems that are

a part of the "Rio Branco-Rupununi Complex", which covers parts of

Brazil and Guyana (Eden, 1970; Sarmiento and Monasterio, 1975). Its components

range from low-altitude grasslands (< 100 m) to arborous types at higher

altitudes (> 1000 m). It is the largest continuous block of savannas in the

Amazonian Biome (± 40,000 km2). The climate of this area is Awi

under the Köppen Classification (Lameira and Coimbra, 1988), with 1100-1700 mm

of annual precipitation and 100-130 days with rain per year (Barbosa, 1997).

The driest months are between December and March (± 10% of the annual

precipitation) and the peak of the rainy season is between May and August (±

60% of the annual precipitation). The relief that supports this landscape

increases in altitude as one moves from the center-south to the

north-northeast, beginning at approximately 80-100 m in the area of the Boa

Vista Formation, increasing in the Surumu Formation and remaining in the

250-900-m range as one approaches the high-altitude (> 1000 m) areas of the

Roraima Group (Brazil, Projeto RADAMBRASIL, 1975).

[* * *

Figure 1 here ****]

3.

Ecosystems studied

Characterization of the

ecosystems in this study followed the Brazilian vegetation classification

system (Brazil, IBGE, 1992), together with the definition adopted for Central

Brazilian savannas (Coutinho, 1978; Ribeiro and Walter, 1998). This

characterization is important because the dynamics of fire in each ecosystem is

different, provoking unequal effects in the area burned and in the fire

frequency. The ecosystems (original and transformed) investigated in the

present study are presented in Table 1.

[* * *

Table 1 here ***]

4. Sampling

methodology

4.1.

Sampling Transect

The total area burned annually and

the frequency of burning of each ecosystem were represented through periodic

observations along a triangular sampling transect covering a linear distance of

540.1 km. The transect cuts through all of the vegetation types defined above

(see Figure 1). Nine points formed the basis for alignment of the transect:

Point 0 (initial) - close to the city of Boa Vista in the Rio Branco valley (2o

47' 39" N; 60o 39' 59" W), Point 1 – in the Tacutu-1 River

valley (3o 18' 40" N; 59o 56' 50" W), Point 2 -

in the Tacutu-2 River valley (3o 48' 4" N; 59o 44'

14" W), Point 3 - Raposa/Serra do Sol Indigenous Land (4o 10'

42" N; 60o 31' 36" W), Point 4 – in the Cotingo River

valley (4o 24' 13" N; 60o 20' 57" W), Point 5 –

in the Surumu River valley (4o 11' 38" N; 60o 47' 31"

W), Point 6 - São Marcos Indigenous Land (4o 13' 51" N; 61o

0' 56" W), Point 7 – in the Uraricoera River valley (3o 27'

49" N; 60o 54' 39" W) and Point 8 (endpoint) - city of Boa

Vista in the Cauamé River valley (2o 52' 9" N; 60o

41' 50" W).

In the first passage along the

transect (June-July 1997: rainy season and without burning) we determined and

recorded the limits of each ecosystem (original and transformed) based on the

number of kilometers traveled by the vehicle used during the whole study. The

structural variations among the original systems studied were defined based on

the crown cover of the arboreal individuals (Table 1). Because it would be impractical to measure

each individual along the 540.1-km transect, we classified the savannas based

on our personal experience in visual observation of the general aspect of these

vegetation types. We considered the original savannas to be all of the

landscapes where the visual appearance of the cover was in accord with the

definition of IPCC/OECD (1994), in other words,"... with continuous grass cover, occasionally

interrupted by trees and bushes..." under different densities. Both “other”

and “anthropic” ecosystems were identified within the “savanna” and

“steppe-like savanna” great groups, but burning in these areas was not counted,

as this has been the subject of a separate study (Barbosa and Fearnside, 1999).

With the linear total

(in km) corresponding to each ecosystem, it was possible to infer the burned

area (%) and the frequency of the fire for each ecosystem through the

quantification of the linear kilometers reached annually by the fire. This was

important to avoid the whole area of savannas being considered a block that

suffers the impacts of the fires equally, independent of the climatic type of

the year (normal, dry or humid), the vegetation type or the geographical

location of the site.

4.2. System

of measurement

The transect was driven by car every

60 days in the rainy season and monthly in the dry season, during three years from

June-July 1997 to April-May 2000, totaling 12,962.4 km of transect in 24 trips.

On each trip a log was made of the initial and final number of kilometers

traveled and of the burned areas on each side of the highway. Occasional fires

in small areas along the edge of the highway were discarded and the linear

distances were only used where the landscape had suffered burning over a long

distance, independent of the observer being able to see the entirety of the

portion of the burn that extends away from the road. In this method we assumed

that each side of the highway had independent fire behavior, although there is

a probability of the fire moving across the highway because some burning plant

material is carried by the wind. At the end of each measurement we computed an

average for each vegetation type in each period.

With each passage along the transect

we made a correction of the values recorded for distance, using as a reference

the first sampling done in the rainy period (June-July1997). This was necessary

in order to avoid distortions due to the tires of the vehicle having different

air pressure and different amounts of wear on each trip and because of the

expansion of the tires due to the varying temperatures (environmental and

material) over the course of the sampling period. A test done before the second sampling

demonstrated that these factors could influence the measurement by up to 3 km

over the course of the transect. To lessen this effect, verification points

were established to allow calibrating the measures obtained on each trip. The

number of kilometers traveled was recorded in units of 0.1 km.

4.3.

Treatment of the data

To obtain an overall

average of burned area and of fire frequency for the three years of

observation, as recommended by the IPCC (1997), we used a weighting system

based on the individual average for each year, considered the proportion of

years classified as dry, humid and normal. This took advantage of our

observations in years classed as “El Niño” (1997/1998), “La Niña” (1998/1999)

and “normal” (1999/2000). We used measurements of annual precipitation between

1966 and 1999 at the Meteorological Station of Boa Vista to determine how many

years were below one standard deviation of the mean (dry years), above one

standard deviation (humid years) or within one standard deviation (normal

years). We estimated that the distribution of these climatic characteristics

for the current period would be 18.2% for years considered to be dry, 21.2% for

humid years and 60.6% for normal years. These values represent approximately

the proportions of a normal distribution for data collected systematically

(Zar, 1974, pp. 73-76).

All of the data were

grouped into two-month periods representing climatically similar intervals:

June-July (peak of the rainy season), August-September (end of the rainy

season), October-November (between seasons), December-January (beginning of the

dry season), February-March (peak of the dry season) and April-May (beginning

of the rainy season). This set of two-month periods totaled 18 (n) values

distributed over the three years of data collection. Graphs of the dynamics

were plotted for the burning (% area burned), and the fire frequency was

calculated in each of the ecosystems starting from the overlapping of values

over the sample period. Finally, a simple regression model was derived to

estimate the percentage (%) of burned area in the Sg (clean field + dirty

field) ecosystem, based on precipitation data obtained from the Meteorological

Station of Boa Vista.

5. Results

5.1. Burned

area

The weighted mean

percentage of area burned annually for all the original ecosystems of “savanna”

and “steppe-like savanna” studied in Roraima was 38 ± 12 (SD)% (Table 2). The

absolute values pointed to an accentuated variation in the 1997/1998 (dry)

biennium (53%), in comparison with 1998/1999 (wet) (30%) and 1999/2000 (normal)

(36%). The steppe-like savanna ecosystems (high altitude) had the highest mean

area burned annually (46 ± 21%), followed by the low- and mid-altitude savannas

(35 ± 9%). Individually, the vegetation types with the lowest densities of

trees (grassy-woody) of the steppe-like areas had the largest values for burned

area: Tg–clean field (85 ± 6%) and Tg–dirty field (57 ± 14%). The vegetation

type with the smallest individual value was the type with the highest crown

cover of trees in the areas with low and middle altitudes: Sa (27 ± 17%).

[*

* * * TABLE 2 here*****]

Of the total area burned annually,

90.9% occurred between October and March (October-November = 23.3%;

December-January = 39.1%; February-March = 28.6%). The remainder occurred in

August-September (7.1%) and April-May (2.1%), with June-July having no

incidences of burning (Table 3; Figure 2).

[*

* * * TABLE 3 here****]

[

* * * FIGURE 2 here ****]

5.2.

Frequency of burning

The individual values

for each biennium indicated that almost all of the locations were only reached

by fire once (1997/1998=99.6%; 1998/1999=99.6%; 1999/2000=98.4%) in every

sampled year (Table 4). The recurrence of fires within a given year was 0.4%

(1997/1998), 0.4% (1998/1999) and 1.6% (1999/2000). Of the total area (weighted

average) burned in the three sampled years, 56% burned only once. The remainder

was distributed among the areas that burned two (34.3%), three (9.1%) or four

(0.6%) times. This means that the average interval between one-time fire events

was 1.8 years; the interval between occurrences of two burns in succession was

2.9 years, while three-burn sequences occurred once every 11 years and

four-burn sequences once every 159 years. These values imply that the mean time

of recurrence of fires in a given area for all the original ecosystems studied

was 2.5 years (30 months).

[****TABLE

4 here ****]

On average, 70-80% of the areas

burned in one year are not affected by new fires the following year (Table 5).

Only 20-30% of the burned areas repeat the same place as the previous year.

[****TABLE

5 here ****]

5.3. Burned

area × precipitation (regression model)

Precipitation data from

Boa Vista (1997 to 2000) have a strong association with the percentage of area

burned in the Sg ecosystem (clean field + dirty field), which includes the area

surrounding that city (Figure 3). A

regression model using data from two-month periods explains 66.2% of the

variance in percentage area burned based on the average daily rainfall (mm/day)

in the same two-month period (Figure 4):

Y = 11.801 – 4.254 ln(X)

Where Y = percentage (%) of burned

area in the two-month period and, X = daily mean precipitation for the same

period (mm.day-1)

[* * * *

Figure 3 here ****]

[* * * *

Figure 4 here **** ]

6.

Discussion

6.1. Burned

area

The weighted average of

38% (27-85%) for total percentage area burned annually determined in this study

for Amazon savannas in Roraima is similar to the 40% value used by Seiler and

Crutzen (1980) for savannas worldwide based on the work of Deschler (1974) for

African savanna between 5o N and 12o N and of Fearnside

(1978) for Amazonian pastures. However, the value is much lower than the 75%

suggested by Menaut and Cesar (1982) and used by Hao et al. (1990) and Hall and

Rosillo-Calle (1990) as the average for the African savannas. Later this number

was revised to 50% in Hao and Ward (1993) and Hao and Liu (1994) and used as

the overall average by different authors in the early 1990s for calculating

emissions of gases from biomass burning in savannas in the tropics as a whole.

Although data of Lavenu (1982, 1984), cited by Menaut et al. (1991), reported

more conservative estimates (25-49%) in studies using LANDSAT imagery of the

Sahelian Zone of the Ivory Coast, the 75% value was still used in some studies.

Our study also found some high values for low-biomass ecosystems (e.g., 85% for Tg–clean field). This

serves to reinforce the need to associate the results of burned area with the

respective vegetation types in order to avoid misunderstandings arising from

use of a single value for all savanna ecosystems.

The first attempts to

distribute the estimates among different types of ecosystems were made by

Delmas et al. (1991) and Menaut et al. (1991) in spatial analyses of the total

biomass burned in savannas in Africa (10-70%). Scholes (1995), in an evaluation

of greenhouse-gas emissions in southern Africa, also distributed his evaluation

among vegetation types, ranging from semi-desert (± 0.1%) to humid ecosystems

(± 53%). Recent studies by Barbosa et

al. (1999a,b) and Pereira et al. (1999) used the AVHRR sensor in

central-African savannas to estimate annual averages for different

phytogeographical zones of 19-36% (1981-1991), 3-70% (1985-1987 and 1990-1991)

and 61% (1996) (P. M. Barbosa and J. M. Pereira, personal communication, 2000).

All of these values represent scenarios and assumptions that are still little

studied and that contain large uncertainties due to the scales and the spatial

resolutions used. The results for annual means determined for the savannas of

northeast Roraima are of a magnitude similar to the overall average of the

results of the African studies mentioned above.

In Brazil, no

on-the-ground studies exist that determine the percentage area burned in open

ecosystems. Kauffman et al. (1994) reported an annual estimate of 50% for

Central Brazilian savannas, but the calculation source is not indicated. IPCC

(1997, p. 4.25) uses the same value as the “default” in spreadsheets for

emission calculations for the whole of Tropical America, citing Hao et al.

(1990). The preliminary Brazilian national inventory estimates emissions of

gases from burning in non-anthropic savannas by using LANDSAT-TM imagery

associated with information on “hot pixels” detected by AVHRR (Brazil, MCT,

2002). The MCT study concluded that, of the total area burned in savannas

throughout Brazil in 1999, 8.3% was in clean and dirty field (Sg) types, 14.8%

was savanna parkland (Sp), 66.4% arborous savanna (Sa) and 10.5% was

“cerradões” (Sd). This last type is counted as forest, rather than savanna, in

the reports on land-use change in forest ecosystems (see Brazil, INPE, 2002).

This distribution of burned area done by MCT (Brazil, MCT, 2002) uses the

studies by Krug et al. (2001), considering the concentration of “hot pixels” in

the different ecosystems. However, this method does not address the question of

whether the concentration of “hot pixels” is really a function of the area

burned, of the size of the ecosystem or of the persistence of the hot pixels

(their persistence will be longer or shorter depending on the vegetation

structure and the amount of biomass present).

Recently, Krug et al. (2004) drew inferences about the area burned and

the recurrence of fires in two LANDSAT scenes in the cerrado of central Brazil

using images from LANDSAT-5 TM and LANDSAT-7 ETM for the 1996-2000 period. One can calculate from the results of the

study the total area burned declined from 13.8-15.5% (1996) to 4.4-7.0%

(2000). Although the study has a

reasonably complete sequence of scenes (20 scenes out of a possible 50 (40%)

for a sampling period of 160 days of draught), there are still time gaps that

are sufficient to mask any growth of the vegetation and hide the true spatial

extent to the burning.

Our data from Roraima

indicate that the mean percentage of area burned in two-month periods is

directly related to (1) human presence, (2) spatial heterogeneity of the

biomass, and (3) fire behavior in response to climatic conditions in the year

of the observation. Lamotte and Bruson (1985 [1990]) cited by Menaut et al.

(1991), found that when savanna fires occur at the beginning of the dry season

in the Ivory Coast (December or earlier), they consume up to 12% of the total

biomass affected. At the peak of the dry season this value rises to 75%

(January), subsequently falling to 13% (February onwards) at the end of the

burning season. If one makes assumptions regarding affected biomass and burned

area, the distribution presented by Menaut et al. (1991) can be compared to the

monthly estimate for Roraima, where 90% of the burned area appeared in the peak

months of the dry season. This directly influences the total amount of biomass

affected by fire.

6.2.

Frequency of Burning

The African studies indicate

a period of 1-2 years for recurrence of fires in a given area. The same value

(1.5 years) is presented by Lacey et al. (1982) for Australian savannas and by

Eiten (1972) for central-Brazilian savannas. Coutinho (1990) and Hoffmann

(1998) re-estimated the value as 1-3 years for the Brazilian savannas. Our

field results (2.5 years) are higher than the above-mentioned estimates (Table

6).

[***Table

6 here***]

The areas with the

greatest recurrence of fire in the savannas of Roraima were concentrated close

to the headquarters of the cattle ranches and to indigenous villages that the

transect intersected. Multiple burns were associated with the presence of

humans. Fires that spread from (or occurred near) human settlements had shorter

recurrence periods. This result would be expected because fires are typically

anthropogenic. Burning in other areas along the transect, supposedly without

human interference, would result from fires started by humans located in any

part of the local savannas.

An important finding of

our study is it that most (70-80%) of the areas burned in one year do not burn

in the following year. In other words, there is always a high percentage of new

area being burned in the following period.

Similar to our finding in Roraima, the studies by Krug et al. (2004) in

central Brazil and by Barbosa et al. (1999a) in central-African savannas found

that, respectively, only 16-18% and 9% of the areas burn regularly over time;

the remainder of the burning is in new areas. This result implies that the

dynamics of fire in these areas lead to a variety of scenarios for the amount

of biomass and carbon exposed to burning over time and in different areas. The

amount of biomass present is not a fixed value from one year to the next. The

rates of biomass increment and carbon should be a function of the dynamics of

entrance and exit of material from the ecosystem due to the recurrence of the

fires.

With regard to the number of fires

occurring in a single year, our study found that, of the total of area burned

in a single year, almost all (± 99%) burns only one time. The complete recovery

of the low vegetation, which is the principal fuel, is slow and takes at least

4-5 months in years considered to be humid and 6-7 months in years defined as

normal. Before this interval of time elapses there is a reduced chance of

accumulation of enough biomass to sustain a fire with high intensity and

lingering duration. Cases of double

burning in a single year are rare (± 1%) and, in general, are observed in places

that burned at the end of the dry season of one year, followed by a reburning

at the end of the rainy season in the same year.

6.3. Burned

area × precipitation (regression model)

Figures 3 and 4

indicate that the burning patterns observed in 1997/1998, 1998/1999 and

1999/2000 are explained as a function of rainfall. These results reinforce the

importance of the distribution of the measures of burned area not only for

ecosystems, but also for the different climatic conditions at each study site,

when applied in calculations of emission of gases from savanna burning.

6.4.

Sampling errors

In general, one might

infer that the frequency of fires and the percentage of burned area determined

by the method used in the present study could be biased as a measure for the

area as a whole due to the proximity of highways to all of the fires observed.

This inference could come from the fact that the highways are the starting

points of development projects and ranches, which would change the density of

the vegetation along the highway and make it unrepresentative of the vegetation

in the rest of the savanna. However, the highway acts in the same way as any

random transect and would count both fires that started from the area of

influence of the highways and those that did not. We considered that, under

this sampling alternative, fires are virtually

always started by humans (both indigenous and non-indigenous), but that, once

started, the spreading of the fire is independent of human presence. Therefore,

although the sampling error can be considered high, the mean probably would

tend to fall very close to the means that would be obtained by randomized or

systematic surveys. To test this, we made two overflights (80 and 45 linear km)

in April and May 1998 to identify and correct for the error in the estimate of

the value of terrestrial area in Sg and Sp for the 1997/1998 biennium. The

results of the overflights indicated that the terrestrial transect was able to

detect 65-70% of the burned areas (Barbosa, 2001). This result is approximately

equal to the 70% value estimated by Barbosa et al. (1999) for central African

savannas using remote sensing techniques.

7.

Conclusions

(1) values for burned area and fire frequency in the savannas of Roraima

are dependent of the vegetation types (structures) and the elevational position

(the lower the density of trees and the greater the amount of grassy vegetation

in high-altitude areas, the greater will be the percentage of burned area);

(2) the amount of burned area is directly related to the climatic type

of the year (dry, wet or normal), which can be inferred from precipitation

parameters using simple regression

models;

(3) on average, 38 ± 12% of the area of all of the savannas present in

Roraima burns annually – a value composed of areas that burn only once in the

year (± 99%) and those that burn more than once (± 1%);

(4) the average frequency of burns for the savannas of Roraima is 2.5

years;

(5) most (70-80%) of the area

burned in one year does not burn the following year, implying time differences

in the approach to calculating biomass dynamics and in models that calculate

the emission of greenhouse gases from savannas;

8. References

Barbosa, R.I. 2001. Savanas

da Amazônia: Emissão de gases do efeito estufa e material particulado pela

queima e decomposição da biomassa acima do solo, sem a troca do uso da terra,

em Roraima, Brasil. Doctoral dissertation.

Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA)/ Universidade do

Amazonas (UA), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. 212 pp.

Barbosa, P.M.; Pereira,

J.M.C.; Grégorie, J.M. 1998. Compositing criteria for burned area assessment

using low resolution satellite data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 65:

38-49.

Barbosa, P.M.;

Stroppiana, D.; Grégorie, J.M.; Pereira,J.M.C. 1999a. An assessment of

vegetation fire in Africa (1981-1991): Burned areas, burned biomass, and

atmospheric emissions. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 13(4): 933-950.

Barbosa, P.M.; Grégorie,

J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C. 1999b. An algorithm for extracting burned areas from

time series of AVHRR GAC data applied at a continental scale. Remote Sensing of

Environment, 69: 253-263.

Barbosa, R.I. 1997.

Distribuição das chuvas em Roraima. In: R. I. Barbosa, E. Ferreira; E. G.

Castellon (eds.), Homem, Ambiente e Ecologia em Roraima. Instituto

Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia (INPA), Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. pp.

325-335.

Barbosa,

R.I.; Fearnside, P.M. 1999. Incêndios na Amazônia brasileira: Estimativa da emissão de gases

do efeito estufa pela queima de diferentes ecossistemas de Roraima na passagem

do Evento “El Niño” (1997/98). Acta Amazonica, 29(4): 513-534.

Brazil, IBGE. 1992. Manual

Técnico da Vegetação Brasileira. Manuais Técnicos em Geociências no

1. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil. 92 pp.

Brazil, INPE 2002. Monitorando

a floresta amazônica brasileira por satélite (2000-2001). Instituto

Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (INPE), São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil.

Brazil, MCT. 2002. Emissões de gases do efeito estufa da queima

de biomassa no cerrado não antrópico utilizando dados orbitais (Primeiro

Relatório Brasileiro de Emissões Antrópicas de Gases do Efeito Estufa – Relatório

de Referência). Coordenação Geral de Mudanças Globais, Ministério da Ciência e

Tecnologia (MCT), Brasília, DF, Brazil. 53 pp.

Brazil, Projeto

RADAMBRASIL. 1975. Levantamento de

Recursos Naturais, Volume 8. Ministério das Minas e Energia. Rio de Janeiro,

Brazil. 428 pp.

Coutinho, L.M. 1978. O

conceito de cerrado. Revista. Brasileira de Botânica, 1: 17-23.

Coutinho, L.M. 1990. Fire in the

ecology of the Brazilian cerrado. In:

J. G. Goldammer (ed.), Fire in the Tropical Biota - Ecosystem Processes and

Global Challenges, Springer-Verlag, Berlin,

Germany. pp. 82-105.

Crutzen,

P.J.; Andreae, M.O. 1990. Biomass burning in the tropics: Impact on

atmospheric chemistry and biogeochemical cycles. Science, 250:

1669-1678.

Delmas,

R.A.; Loudjani, P.; Podaire, A.; Menaut, J.C. 1991. Biomass

burning in Africa: An assessment of annually burned biomass. In: J. S. Levine (ed.), Global

Biomass Burning - Atmospheric, Climatic, and Biospheric Implications.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A.

pp. 129-131.

Deschler,

W.W. 1974. An examination of the extent of grass fires in the savanas of Africa

along the southern side of Sahara. In: Ninth International Symposium on

Remote Sensing of Environment, ERIM, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A.

Eden, M.

1970. Savanna vegetation in the northern Rupununi, Guyana. The Journal of

Tropical Geography, 30: 17-28.

Eiten,G.

1972. The cerrado vegetation of Brazil. Botanical Review, 38: 201-341.

Fearnside, P.M. 1978. Estimation

of Carrying Capacity for Human Populations in a part of the Transamazon Highway

Colonization Area of Brazil. Ph.D. dissertation in biological sciences,

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. University Microfilms International, Ann

Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. 624 pp.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1996. Amazonia and global warming: Annual balance of greenhouse gas

emissions from land-use change in Brazil's Amazon region. In: J. S.

Levine (ed.), Biomass Burning and Global Change (vol. 2). Massachusetts

Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. pp. 606-617.

Fearnside,

P.M. 1997. Greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia:

Net committed emissions. Climatic Change,

35: 321-360.

Greenberg,

J.P.; Zimmerman, P.R.; Heidt, L.; Pollock, W. 1984. Hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide

emissions from biomass burning in Brazil. Journal of Geophysical Research,

89(D1): 1350-1354.

Hall, D.;

Rosillo-Calle, F. 1990. African forests and grasslands: Sources or sinks of

greenhouse gases ? In: International Conference on Global Warming &

Climate Change: African Perpectives. Nairobi, Kenya (2-4 May). 23 pp.

Hao, W.M.;

Ward, D.E. 1993. Methane production from global biomass burning. Journal of

Geophysical Research, 98(D11): 20657-20661.

Hao, W.M.;

Liu, M.H. 1994. Spatial and temporal distribution of tropical biomass burning. Global

Biogeochemical Cycles, 8(4): 495-503.

Hao, W.M.;

Liu, M.H.; Crutzen, P.J. 1990. Estimates of annual and regional releases of CO2

and other trace gases to the atmosphere from fires in the tropics. Based on the

FAO Statistics for the period 1975-80. In: J. G. Goldammer (ed.),

Fire in the Tropical Biota. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp. 440-462.

Hoffa, E.A.;

Ward, D.E.; Hao, W.M.; Sussot, R.A.; Wakimoto, R.H. 1999. Seasonality of carbon

emissions from biomass burning in a Zambian savanna. Journal of Geophysical

Research, 104(D11): 13841-13853.

Hoffmann,

W.A. 1998. Post-burn reproduction of woody plants in a neotropical savanna: The

relative importance of sexual and vegetative reproduction. Journal of

Applied Ecology, 35: 422-433.

Houghton,

R.A. 1990. The future role of tropical forests in affecting the carbon dioxide

concentration of the atmosphere. Ambio, 19(4): 204-209.

Houghton,

R.A.; Hobbie, J.E.; Melillo, J.M.; Moore, B.; Peterson, B.J.; Shaver, G.R.; Woodwell,

G.M. 1983. Changes in the carbon content of terrestrial Biota and soils between

1860 and 1980: A net release of CO2 to the atmosphere. Ecological

Monographs, 53(3): 235-262.

Houghton,

R.A.; Lawrence, K.T.; Hackler, J.R.; Brown,S. 2001. The spatial distribution of

forest biomass in the Brazilian Amazon: A comparison of estimates. Global Change Biology, 7: 731-746.

IPCC, 1997.

Greenhouse Gas Inventory: Reporting Instructions, Vol. 2. In: J. T.

Houghton; L. G. Meira-Filho; B. Lim; K. Tréanton; I. Mamaty; Y. Bonduki; D. J.

Gribbs; B. A. Callander (eds.), Revised 1996 IPCC Guidelines for National

Greenhouse Gas Inventories. IPCC/OECD/IEA. Geneva, Switzerland. pp.

4.23-4.27.

IPCC/OECD

1994. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Reporting Instructions (Final Draft).

IPCC Draft Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (Vols. 1 – 2 -

3). IPCC/OECD Joint Programme, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kauffman.

J.B.; Cummings, D.L.; Ward, D.E. 1994. Relationships of fire, biomass and

nutrients dynamics along a vegetation gradient in the Brazilian Cerrado. Journal

of Ecology, 82: 519-531.

Kaufman,

Y.J.; Setzer, A.; Justice, C.; Tucker, C.J.; Pereira, M.C.; Fung, I. 1990.

Remote sensing of biomass burning in the tropics. In: J. G. Goldammer

(ed.), Fire in the Tropical Biota, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp.

371-399.

Krug, T.,

Rivera-Lombardi, R.J.; dos Santos, J.R. 2004. Burned area, recurrence of fires

and permanence of burnt scars in selected areas of the Brazilian cerrado using

TM-LANDSAT imagery. In: XX

International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Congress, Istambul,

12-23 July 2004. (in press)

Krug, T.; dos Santos,

J.R. 2001. Estimativa da área total

queimada no cerrado brasileiro em 1999, a partir de dados orbitais.

Relatório PNUD BRA/95/G31. São José dos Campos, São Paulo, Brazil.

Krug, T.; dos Santos,

J.R.; Miranda, H. 2001. Estimativa da

área queimada no cerrado brasileiro não-antropizado em 1999, a partir de dados

orbitais. Report to the Coordenação Geral de Mudanças Climáticas, Ministério da

Ciência e Tecnologia (MCT), Brasília, DF, Brazil..

Lacey, C.J.;

Walker, J.; Noble, I.R. 1982. Fire in Australian tropical savannas. In:

B. J. Huntley ; B. H. Walker (eds.), Ecology of Tropical Savannas

(Ecological Studies 42). Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Germany. pp. 246-272.

Lameira, O.A.; Coimbra,

J.M. 1988. Levantamento e distribuição da precipitação em Roraima. Pesquisa

em Andamento no 12. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária

(EMBRAPA/UEPAT), Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazil.

Lamotte,

M.; Bruzon, V. 1985 [1990]. Variations saisonnières de la fixation

et de la libération de gaz carbonique dans les milieux de savane de Côte

d'Ivoire . Action des feux de brousse. Paysages, aménagement, cadre de vie.

Mélanges offerts à Gabriel Rougerie. Paris, Publication

de l'Association Française de Géographie Physique et de l'Université Paris

8, Paris, France. pp. 173-186.

Lavenu,

F. 1982. Teledetection des feux de savana dans le Parc National de la Comoe

(Cote-d'Ivore). Dissertation, Université de Paris, Paris, France.

Lavenu,

F. 1984. Teledetection et vegetation tropicale: example du Nord-Est de la

Cote d'Ivore et du Bengladesh. Thesis, Université Provence Sud

(UPS), Toulouse, France.

McNaughton,

S.J.; Stronach, R.H.; Georgiardis, N.J. 1998. Combustion in natural fires and

global emissons budgets. Ecological Applications, 8(2): 464-468.

Menaut, J.C. 1983. The vegetation of African savannas. In: F. Bourlière (ed.) Tropical savannas.

(Ecosystems of the World 13). Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 109-149.

Menaut, J.C.; Abbadie, L. ; Lavenu, F.;

Loudjani, P. ; Podaire, A. 1991. Biomass burning in West African savannas. pp. 133-142 In: J.S.

Levine (ed.) Global Biomass Burning:

Atmospheric, Climatic, and Biospheric Implications. Massachusetts

Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. 640 pp.

Menaut,

J.C.; Cesar, J. 1982. The structure and dynamics of a West Africa Savanna. In:

B. J. Huntley ; B. H. Walker (eds.), Ecology of Tropical Savannas (Ecological

Studies 42). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany. pp. 80-100.

Menaut,

J.C.; Abbadie, L.; Lavenu, F.; Loudjani, P.; Podaire, A. 1991. Biomass burning

in West African Savannas. In: J. S. Levine (ed.), Global Biomass

Burning - Atmospheric, Climatic, and Biospheric Implications. Massachusetts

Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.A. pp. 133-142.

Nascimento, H.E.M.;

Laurance, W.F. 2002. Total aboveground biomass in central Amazonian

rainforests: A landscape-scale study. Forest Ecology

and Management, 168: 311-321.

Pereira, J.M.C.; Pereira,

B.S.; Barbosa, P.; Stroppiana, D.; Vasconcelos, M.J.P.; Grégorie, J.M. 1999. Satellite

monitoring of fire in the EXPRESSO study area during the 1996 dry season

experiment: Active fires, burnt area, and atmospheric emissions. Journal of

Geophysical Research, 104 (D23): 30701-30712.

Pivello, V.R.; Coutinho, L.M. 1992. Transfer of

macro-nutrients to the atmosphere during experimental burnings in an open

cerrado (Brazilian savanna). Journal of Tropical

Ecology, 8: 487-497.

Ribeiro,

J.F.; Walter, B.M.T. 1998. Fitofisionomias do Bioma Cerrado. In: Sano, S.M.;

Almeida, S.P. (eds.), Cerrado - Ambiente e Flora. EMBRAPA,

Planaltina, Distrito Federal, Brazil. pp. 89-166.

Robinson, J.M. 1991. Problems in global fire

evaluation: Is remote sensing the solution? pp. 67-73 In: J.S. Levine (ed.) Global Biomass Burning: Atmospheric,

Climatic, and Biospheric Implications. MIT Press, Boston, Massachusetts,

U.S.A. 640 pp.

Sampson,

R.N. and 32 others. 2000. Additional human-induced activities – Article 3.4.

pp. 181-281 In: R.T. Watson, I.R. Noble, B. Bolin, N.H.

Ravindranath, D.J. Verardo; D.J. Dokken (eds.) IPCC Special Report on Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. 377 pp.

Sarmiento,

G.; Monasterio, M. 1975. A critical consideration of the environmenatl

conditions associated with the occurrence of Savanna ecosystems in Tropical

America. In: F. B. Golley ; E. Medina (eds.), Tropical Ecological

Systems: Trends in Terrestrial and Aquatic Research. Springer-Verlag, New

York, U.S.A. pp. 223-250.

Scholes,

R.J. 1995. Greenhouse gas emissions from vegetation fires in Southern Africa. Environmental

Monitoring and Assessment, 38: 169-179.

Scholes, M.;

Andreae, M.O. 2000. Biogenic and pyrogenic emissions from Africa and their

impact on the Global Atmosphere. Ambio, 29(1): 23-29.

Scholes,

R.J.; Walker, B.H. 1993. An african savanna: Synthesis of the Nylsveley study.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. 293 pp.

Schroeder,

P.E.; Winjum, J.K. 1995. Assessing Brazil’s carbon budget: II . Biotic fluxes

and net carbon balance. Forest Ecology and Management, 75: 87-99.

Seiler,

W. ; Crutzen, P.J. 1980. Estimates of gross and net fluxes of carbon between

the biosphere and the atmosphere from biomass burning. Climate Change,

2: 207-247.

Setzer,

A.W.; Pereira, M.C. 1991. Amazonia biomass burnings in 1987 and an estimate of

their tropospheric emissions. Ambio, 20(1): 19-22.

Ward, D.E.; Sussot,

R.A.; Kauffman, J.B.; Babbitt, R.E.; Cummings, D.L.; Dias, B.; Holben, B.N.;

Kaufman, Y.J.; Rasmussen, R.A.; Setzer, A.W. 1992. Smoke and fire

characteristics for Cerrado and deforestation burns in Brazil: BASE-B

Experiment. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97(D13): 14601-14619.

Zar, J.H.

1974. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey, U.S.A. 620 pp.

FIGURE LEGENDS

Figure

1–South America with the location of Roraima and of the savanna area.

Figure

2–Cumulative percentage area burned for “original” savanna ecosystems in

Roraima in years of different climatic types.

Figure

3--Daily precipitation and area burned in two-month periods for Sg savannas

(clean field + dirty field) in Roraima.

Figure

4—Observed versus calculated area burned.

|

Table 1 - Caracterization of the ecosystems studied. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Macro System (1) |

Ecosystem |

Structural type |

Crown Cover (%) |

Tree stratum (Height) |

Estimated Area (2) (km2) |

Transect length (km) |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Savanna |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sg |

grassy-woody |

clean field |

0 |

Absent |

7929 |

177.8 |

|

|

|

Sg |

grassy-woody |

dirty field |

< 5 |

Minimal |

5759 |

129.1 |

|

|

|

Sp |

parkland |

parkland cerrado |

5-20 |

2-4 m |

11350 |

133.2 |

|

|

|

Sa |

arboreous |

typical cerrado |

20-50 |

3-6 m |

547 |

12.5 |

|

|

|

Anthropic S |

- |

(3) |

- |

- |

- |

20.5 |

|

|

|

Others S |

- |

(4) |

- |

- |

- |

31.9 |

|

|

|

Steppe-like savanna |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tg |

grassy-woody |

clean field |

0 |

Absent |

198 |

1.5 |

|

|

|

Tg |

grassy-woody |

dirty field |

< 5 |

Minimal |

343 |

2.5 |

|

|

|

Tp |

parkland |

parkland cerrado |

5-20 |

2-4 m |

5730 |

19.7 |

|

|

|

Ta |

arboreous |

typical cerrado |

20-50 |

3-6 m |

666 |

10.1 |

|

|

|

Anthropic T |

- |

(3) |

- |

- |

- |

0.5 |

|

|

|

Others T |

- |

(4) |

- |

- |

- |

0.9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) savanna = vegetation situated mainly at altitudes

below 600 m, occupying a mosaic of Ultisol and Oxisol soils; Steppe-like

savanna = vegetation situated mainly at altitudes above 600 m in a mosaic

of litholic soils, including milky quartz. |

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) estimate based on phytoplanimetric maps

(1:250,000) in Brazil, Projeto RADAMBRASIL, 1975. |

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(3) original vegetation modified by human activity

without a reliable estimate of area. |

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(4) other original vegetation that does not fit in

the general definition of savannas; included in this category are terrestrial

ecosystems such as forest islands and gallery forests and aquatic ecosystems

such as rivers and lakes. |

|

Table 6 - Burning frequencies in

savannas

Vegetation type

Location Frequency Source

Derivation

of

burning

(years)

EMISSIONS ESTIMATES

All savannas worldwide 2.5 Seiler and Crutzen, 1980, p. 226

Deschler, 1974;

Fearnside, 1978

All savannas worldwide 2.5± 1.5 Crutzen and Andreae, 1990, p.

1670 Menaut, 1991

Cerrado Brazil (central)

1.5 ± 1.5 Hao et al., 1990 Eiten, 1972;

Sarmiento and Monasterio,

1977

African savannas Africa 1.33 Hao

et al., 1990 Menaut and Cesar, 1982;

Menaut, 1983;

J.C.Menaut, personal

communication

to Hao et al., 1990.

SITE STUDIES

Cerrado Brazil (central)

2 Eiten, 1972

Cerrado Brazil (central)

1-3 Coutinho, 1990, pp.

87-88

Cerrado Brazil (central) 3 Pivello and Coutinho, 1992

Roraima Brazil

(northern) 2.5 This study

savanna (lavrado)

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

![]()