Introduction

Forest fires of great proportions

in areas with high humidity in Amazonia could be considered as rare events, and

only a short while ago few people would have believed that real a danger

existed of such fires taking place (Uhl et al., 1988; Kauffman, 1991; Nelson

and Irmão, 1998). However, in late 1997

and early 1998, fires penetrated primary forests and other types of ecosystems

of the state of Roraima, located in the extreme north of the Brazilian Amazon

(Barbosa, 1998a,b,c; Brazil, IBAMA, 1998; Brazil,

INPE, 1998, 1999a; Shulze, 1998). Fires

in savannas and transformed forest systems (secondary forests, pastures and

clearings), which are traditionally burned at this time of year, spread over

thousands of square kilometers of intact primary forest, provoking the death of

trees and the emission of million of tons of greenhouse gases to the

atmosphere. The enormous size of the

fire was credited, mainly, to the drought provoked by the strong El Niño

phenomenon of 1997-98. However, the

occurrence of the Great Roraima Fire should not be seen as an event caused

exclusively by this climatic effect.

Instead, it was the result of a series of factors acting simultaneously,

with the El Niño aggravating the effect of the pre-existing conditions. At present, the probability of events such as

this can be expected to increase over time due to pressure of human settlements

in forest areas throughout Amazonia, amplified by the increasing logging,

clearing for agriculture and burning for conversion of primary forests to

pastures, all increasing the vulnerability of the adjacent forests (Cochrane et

al., 1999; Kauffman et al., 1988; Negreiros et al., 1996; Nepstad et al., 1999a,b).

Studies are rare that try to

evaluate the risks of fires in Amazonia and their release of greenhouse

gases. With the growth of human

activities in the Amazon, there is a need to increase the volume of information

on the impacts that this type of event can cause at regional and global

levels. With this in mind, we calculated

the emissions of greenhouse gases provoked by the fires in Roraima in different

types of natural systems and agroecosystems that were affected by fire in 1997

and 1998. In order to calculate these

emissions we estimated the following parameters: (a) the area of each natural

system and agroecosystem affected, (b) the total plant biomass (above and below

ground) per unit of area, (c) mortality of trees due to the fire, (d) the

formation of charcoal in the systems affected, (e) burning efficiency for the

different biomass categories that it comprise each system and (f) the

concentration of carbon in each of these categories.

General description of the Area

Roraima is one of the former

federal territories transformed into states by Brazil’s 1988 constitution,

located in the northernmost portion of the Brazilian Amazon. The local population tripled between 1980 and

1998, growing from 82,018 to 260,705 inhabitants (Brazil, IBGE, 1999). The migratory explosion of this period was

motivated by local public authorities in three phases: (a) at the end of the

1970s, with support of the Federal Government as part of the POLORORAIMA

sub-program of the Amazonian Development Poles Program (POLOAMAZÔNIA), (b)

through the “mining boom” in the Yanomami indigenous lands at the end of the

1980s, when the territory was transformed into a state and (c) in the early

1990s through state government programs to recruit migrants in other parts of

the country with land-tenure problems (Barbosa, 1993). The population growth

provoked an increase by 55.6 fold in the total area of deforestation, expanding

from 100 km2 in 1978 to 5,560 km2 in 1997 (Brazil, INPE,

1999b).

The natural vegetation of Roraima

is a mosaic of landscapes that range from savannas (northeast) to forests

(south and west), and different types of oligotrophic (nutrient-poor) systems

such as campos (grasslands), campinas

and campinaranas (low woodlands on white-sand soils) in the center-south

portion of the state (Silva, 1997). The

annual precipitation is variable and forms a gradient from 1000 mm (in the

savannas at the northeast end of the state) up to 2300 mm (southern and far

western parts of the state) (Barbosa, 1997).

The place with largest volume of climatic data is the capital at Boa

Vista. The annual average precipitation

is 1614 mm (1910 to 1995). Between

September 1997 and March 1998 the precipitation was only 30.6 mm in this area,

when the expected amount based on the historical average for same period would

be 352 mm (Brazil, DEFARA and INMET, 1999).

The relative humidity of the air was below 60% between February and

March 1998 (Brazil, MAA/INMET, 1998).

Area of the Natural Systems and Agroecosystems Affected

Original area

To determine the total area

affected by the fire, we estimated the original area of the original vegetation

types in Roraima. We used as a base a

digitization of the vegetation map of Amazonia at a scale of 1:2,500,000

(Brazil, SUDAM and IBGE, 1989), because this base uses the standard

classification typology for Brazilian vegetation described by IBGE (1992). After the macrospatial determination of the

types that make up the regional landscape, the map was scanned and color-coded

to facilitate measurement of the original areas. Based on field observations and on a mosaic

of LANDSAT-TM satellite images (1:1,000,000) (Roraima, SENAGRO and ITERAIMA,

1996), we made adjustments and modifications to the digitized map due to some

inaccuracies, such as grasslands erroneously denominated as savannas or dense

forests defined as ecotones. Using

IDRISI (Eastman, 1995), a computer program that analyzes geographical data for

spatial classification, we estimated the number of picture elements (pixels) in

each vegetation type and calculated the proportional area of each category,

considering the total area of Roraima as 225,116 km2.

To estimate the net area present in

1997-98 for each original vegetation type, two types of adjustments were

applied to the calculated areas: (a) for human-altered areas (rural and urban)

and (b) for watercourses (major rivers).

The rural areas were quantified based on the results obtained by the

National Institute for Space Research (Brazil, INPE, 1999b) for areas

deforested up to 1997, updated to 1998 based on the mean annual area of

deforestation for the 1992-1997 period.

The distribution of deforested areas among pasture, agriculture and

secondary forests up to 1997-98, was obtained from the proportions based on the

mean of four results: (a) the 1985 agricultural census (Brazil, IBGE, 1985),

(b) the 1995-1996 agricultural census (Brazil, IBGE, 1996), (c) Fearnside (1996)

for three equilibrium landscapes in the year 1990 and (d) the summary of the

National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) diagnostic

evaluation of settlements in Roraima 1998-1999 (Luz, 1999). The areas determined for the three human-altered

categories were subtracted from the forest eco-region to which each belonged,

in proportion to the number of linear kilometers of existing access roads in

each system, assuming a direct relationship between roads and deforested areas. The urban areas were computed by

extrapolation of the mean number of pixels contained in each county seat. Adjustments were made in the same way as

those for rural human-altered areas, subtracting from the area of the landscape

type where the each city is located. To

estimate the area of the major watercourses we used the same procedure as that

used for the calculation of the typological units.

Area Burned

In order to calculate the area

affected by fire in each type of forest or oligotrophic vegetation we digitized

the geographical coordinates obtained in 16.5 hours of overflights by Barbosa

(1998b) in the Geographical Information System (SGI/INPE, version 7.0) at the

Executive Secretariat of the Ecological-Economic Zoning of Roraima (ZEE/RR). Additions and corrections were applied to the

original limits of these geographical points based on field observations and,

in the case of analysis of LANDSAT-TM and DMSP satellite images, based on

partial reports presented by INPE (1998, 1999a). Once this was done, three blocks were

established distributed along the border between the forest and the

savanna. These blocks represented the

major regional divisions where the fire was present: (a) Block 1: eastern

section, between the left bank of the Rio Branco and the Rio Tacutu (Cantá--RR

170 Highway-–Anauá River), (b) Block 2: western section; between the right bank

of the Rio Branco and the Rio Uraricoera (Caracaraí–-Rio Uraricoera) and (c)

Block 3: northern section; between the left bank of the Rio Uraricoera and the

right bank of the Rio Tacutu (Maracá Island--Pacaraima). In addition, the blocks were subdivided into

zones for different intensities of burning in the forest: (a) high intensity,

or more than 50% of the forested area affected, (b) medium intensity, or between

5 and 50% affected and (c) low intensity, or below 5% affected (but with some

alterations). The intensity zones

received different treatments in the analysis.

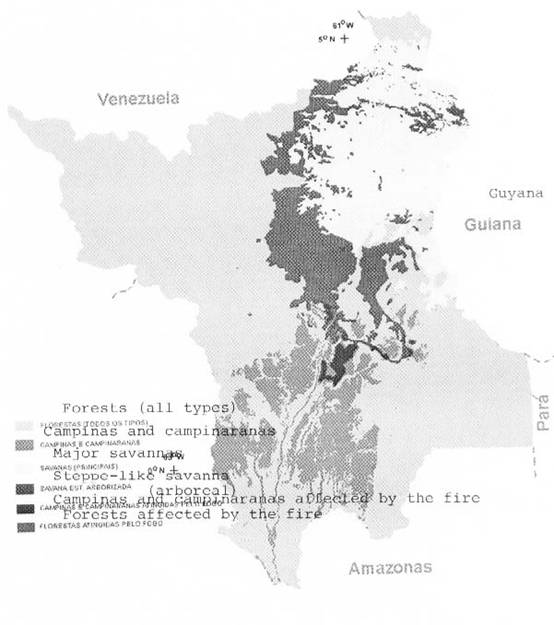

The blocks were overlayed on the

vegetation base map derived from the map of SUDAM and IBGE (1989) in order to

estimate the area affected by the fire in each type of forest or oligotrophic

vegetation (grasslands, campinas and campinaranas). The affected area represented the total area

where the fire was present (Fig. 1).

However, for the forest systems, it was necessary to adjust for

human-affected areas, watercourses, and other unburned landscapes, etc., in

order to avoid double-counting and/or counting habitats that did not burn. In addition, the area of forest (already

adjusted) also had to be adjusted based on the intensity of burning at the

site. This was due to the distinct

behavior of the fire in each of the intensity zones. Because of this, we defined a burning factor

for each of the areas based on aerial photographs obtained in the overflights

made during and after the fires. Based

on this methodology, the area of forest effectively burned (the area where the

fire really provoked some kind of damage to the system) was 11,394 km2

(Table 1).

[Figure 1 and

Table 1 here]

|

Table 1 - Area

(km2) of intact forest affected and effectively burned in each

impact zone (Total for all blocks).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gross area affected

(km2)

|

Deductions

|

Net area

affected

(km2)

|

Mean burn factor (1)

(%)

|

Area

effectively

burned

(km2)

|

Mean burn factor (2)

(%)

|

Area

effectively

burned

(km2)

|

|

Impact

zone

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rivers

(km2)

|

Other natural environments

(km2)

|

Human-altered environments

(km2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High Impact

|

13,687

|

120

|

981

|

1,789

|

10,797

|

85.1

|

9,189

|

-

|

-

|

|

Medium Impact

|

6,022

|

48

|

416

|

1,145

|

4,413

|

33.7

|

1,487

|

-

|

-

|

|

Low Impact

|

1,583

|

12

|

23

|

320

|

1,229

|

7.3

|

90

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total

|

21,292

|

180

|

1,419

|

3,253

|

16,439

|

52.7

|

10,766

|

80.9

|

13,299

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High Impact

(SN)(3)

|

2,049

|

17

|

0

|

20

|

2,012

|

31.2

|

628

|

-

|

628

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total

|

|

23,341

|

198

|

1,419

|

3,273

|

18,451

|

-

|

11,394

|

|

13,928

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) calculation considering the burn factor for each block and

impact zone.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) calculation considering the burn factor determined by

IBAMA (1998) for the total area of the fire in forest systems.

|

|

(3) SN - area

of ecological tension; contact savanna / seasonal forest. This was determined together with the transects in the savannas because they cut this

landscape type. This calculation was done separately.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emissions estimates are subject to

a high degree of uncertainty due to the fire being restricted to surface

burning that did not provoke stress in the crowns of the trees in some places

and, therefore, was not detected by either the aerial photographs or the

satellite images. We therefore estimated

a range for the burned area for the purpose of calculating emissions. The lower bound of this range was formed by

the value calculated above and the upper bound by using the burning factor observed

by a ground team mounted by the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and

Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA) (Brazil, IBAMA, 1998), which found 80.9% of

the forest area to have some damage by the fire (effectively burned),

independent of fire intensity. Applying

this percentage to the total area affected, we determined the range for area

effectively burned as 11,394-13,928 km2 or, 7.4-9.0% of the whole

forested area present. We use the

midpoint of this interval to calculate the emissions.

Our current estimate is higher than

the first results estimated by Barbosa (1998a,b) from overflights of the

affected areas (7800-9200 km2) and by INPE (1999) from LANDSAT-TM

satellite images (11,730 km2).

In the first case, several areas were not quantified due to the limited

aerial coverage and, in the second, the limit was due to the quality of the

images and the impossibility of detecting ground fires that did not stress the

leaf cover of the trees. However, in any

of the above-mentioned estimates, the values are greater than the total area

deforested in Roraima up to 1997 (5560 km2) and much higher than the

estimates announced previously by the government for the Great Roraima Fire

(3000 km2) (Braga, 1998).

With respect to the procedure to

determine the proportion of area burned in human-affected systems (pasture,

secondary forests and agricultural fields), we made four ground transects

distributed in the fire-impact zones (described above): (a) Transect 1 (medium

impact): 147 km between Cantá and Vila União (RR 170), (b) Transect 2 (low

impact): 76 km connecting the towns of Novo Paraíso (BR 174/210), Martins

Pereira, Vila Moderna and back to Novo Paraíso, (c) Transect 3 (medium impact):

60 km between the town of Mucajaí and the boundary between Iracema and

Caracaraí counties and (d) Transect 4 (high impact): 64 km from side road (vincinal)

No. 1 of the Apiaú settlement area, side road No. 9, cross-cutting access road

(travessão) No. 9, Ribeiro Campos and side road No. 7. In each of these transects we quantified the

number of lots

that were affected by humans in each category (pasture, secondary forest or

agricultural fields) and condition (burned or unburned). We then estimated the mean percentage of

burned area by fire-impact zone in these transformed forest habitats. Of the 5776 km2 of human-affected

areas present in Roraima up to 1998 (including 220 km2 of new

clearings), we calculated that 48.1% (2780 km2) had been effectively

burned. The highest burning factors were

found for the areas located in the high fire-intensity zones, for secondary

forests (73.7%) and pasture (62.7%). The lowest factor was found for

agricultural fields in the areas with low burning intensity (15.4%).

For the oligotrophic systems, the

total burned area was estimated to be 1388 km2, taking into

consideration the procedures adopted previously. For the calculation of the total area burned

in the savannas, the procedure (Barbosa, 1998b) uses the measurements made

between July 1997 and June 1998 on the transects established along 540.1 km of

highways that cut through all of the main types of savannas in Roraima. The burned area of this landscape totaled

22,583 km2. A summary of the

original areas and of the effectively burned area by vegetation type is given

in Table 2.

[Table 2 here]

|

Table 2 - Original area and

area effectively burned of the vegetation types (natural and agroecosystems)

present in Roraima in 1997-98.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Area 1997-98 (km2)

|

Percent of area burned

relative to the area present

|

|

Category

|

Code

|

Group

|

Sub-group

|

Class

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Present

|

Effectively

Burned

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dense forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Da-0

|

ombrophilous forest

|

dense forest

|

alluvial

|

2,573

|

0

|

0.0

|

|

|

Db-0

|

ombrophilous forest

|

dense forest

|

lowland

|

7,959

|

0

|

0.0

|

|

|

Dm-0

|

ombrophilous forest

|

dense forest

|

montane

|

21,457

|

0

|

0.0

|

|

|

Ds-0

|

ombrophilous forest

|

dense forest

|

submontane

|

72,,821

|

2,657

|

3.6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total, Dense Forest

|

|

|

|

104,810

|

2,657

|

2.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-dense

forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As-0

|

ombrophilous forest

|

open forest

|

submontane

|

8,197

|

4

|

0.0

|

|

|

Fs-0

|

seasonal forest

|

semidecíduous

|

submontane

|

1,286

|

485

|

37.7

|

|

|

ON-0

|

areas of ecological tension

and

contact

|

|

ombrophilous forest /

seasonal forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

17,230

|

7,010

|

40.7

|

|

|

SN-0

|

areas of ecological tension

and

contact

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

savanna / seasonal forest

|

1,975

|

628

|

31.8

|

|

|

SO-0

|

areas of ecological tension

and

contact

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

savanna / ombrophilous

forest

|

4,456

|

215

|

4.8

|

|

|

LO-0

|

areas of ecological tension

and

contact

|

|

vegetation woody

oligotrophic formations of swamps and white sand areas / ombrophilous forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

16,674

|

394

|

2.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total, Non-dense Forest

|

|

|

49,817

|

8,737

|

17.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ld-0

|

oligotrophic woody

vegetation

of swamps and white sand

areas

|

arboreal dense

|

12,256

|

524

|

4.3

|

|

|

La-0

|

vegetation woody

oligotrophic

of swamps and white sand

areas

|

|

arboreal open

|

134

|

0

|

0.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lg-0

|

vegetation woody

oligotrophic

of swamps and white sand

areas

|

|

grassy-woody

|

11,573

|

864

|

7.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total, Oligotrophic

formations

|

|

|

|

23,962

|

1,388

|

5.8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

rm-0

|

ecological refuge

|

high altitude

|

montane

|

205

|

32

|

15.5

|

|

|

Sg-0

|

savanna

|

savanna

|

grassy-woody

|

15,004

|

7,932

|

52.9

|

|

|

Sp-0 (2)

|

savanna

|

savanna

|

park

|

12,443

|

7,329

|

58.9

|

|

|

Td-3 (2)

|

steppe-like savanna

|

Roraima grasslands

|

arboreal dense

|

2,313

|

1,779

|

76.9

|

|

|

Tp-3

|

steppe-like savanna

|

Roraima grasslands

|

park

|

8,733

|

5,511

|

63.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total, Savannas

|

|

|

|

38,697

|

22,583

|

58.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-altered(1)

|

Rural

|

pastures

|

|

|

3,063

|

1,538

|

50.2

|

|

|

|

secondary forests

|

|

|

1,699

|

854

|

50.3

|

|

|

|

agricultural fields

|

|

|

794

|

169

|

21.2

|

|

|

|

deforestation in 1998

|

|

|

220

|

220

|

100.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sub-total Human-altered

|

|

|

|

5,776

|

2,780

|

48.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban

|

cities

|

|

|

251

|

0

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Watercourses(3)

|

|

|

|

|

1,803

|

0

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total area (km2)

|

|

|

|

|

225,116

|

38,144

|

16.9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Rural: considered as

change in land use only in forest areas, especially in the vegetation types

Ds, ON, Fs, LO and As; Urban: municipal seats (distributed as

|

|

follows: 5 for Ds; 4 for ON; 1 for LO; 1 for SN; 2 for Sg; 1

for Sp and 1 for Tp). Areas deforested in the year of the fire were

considered to be totally accessible to the fire.

|

|

(2) Sp represents, for

calculation purposes, the sum of Sp and Sa, and Td represents, for

calculation purposes, the sum of Td and Ta.

|

|

|

|

(3) Represents the

principal rivers of Roraima

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total Original Plant Biomass

Present biomass

The calculation procedure for most

of the forest eco-regions (dense and non-dense), was based on the

volume-expansion method (m3/ha) and biomass (t/ha) calculation of

Brown and Lugo (1992), adjusted by the method of Fearnside (1992). For Roraima, this method underwent

adjustments in the categories "dead above-ground biomass" and

"below-ground biomass." For

these two items, new studies were added to those adopted previously by

Fearnside (1992), such as one for Maracá Island (Scott et al., 1992; Thompson

et al., 1992; Nascimento, 1994; Villela, 1995) and, discarded others that did

not fit the characteristics of vegetation types present in Roraima. Regional-scale volumetric data (m3/ha)

were obtained from volumes 8, 9, 10, 11, 14 and 18 of Projeto RADAMBRASIL

(1975-1978), which cover the whole State of Roraima and neighboring areas where

vegetation types similar. The mean total

biomass (weighted by area) of all dense forests was 320 t/ha and, of non-dense

forests was 279 t/ha (Table 3). In both

cases, there is a reduction of 25% and 34%, respectively, with respect to the

estimates by Fearnside (1997b) for carbon emissions from deforestation in

Roraima in 1990.

[Table 3 here]

|

Table 3 - Total

biomass estimated by vegetation type (t/ha) in Roraima in1997-98.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Biomass (t/ha)(2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category

|

Code

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above-ground

|

Below-ground

Live

|

Total

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Live

|

Dead

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dense forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Da-0

|

275

|

21

|

47

|

343

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Db-0

|

276

|

21

|

47

|

345

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dm-0

|

232

|

18

|

40

|

290

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ds-0

|

261

|

20

|

45

|

326

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted average, Dense

forest

|

257

|

20

|

44

|

320

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-dense

forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Os-0

|

226

|

17

|

39

|

283

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fs-0

|

226

|

17

|

39

|

283

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ON-0

|

226

|

17

|

39

|

283

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SN-0

|

158

|

12

|

27

|

197

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SO-0

|

158

|

12

|

27

|

197

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LO-0

|

234

|

32

|

40

|

306

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted average, Non-dense

forest

|

220

|

22

|

38

|

279

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-forest

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ld-0

|

39.8

|

7.8

|

69.0

|

117

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La-0

|

33.8

|

5.0

|

21.3

|

60

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lg-0

|

5.8

|

3.7

|

42.0

|

52

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted average, Oligotrophic formations

|

23.3

|

5.8

|

55.7

|

85

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

rm-0

|

2.7

|

0.4

|

10.0

|

13

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sg-0

|

2.9

|

0.4

|

10.9

|

14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sp-0

|

5.4

|

0.6

|

20.3

|

26

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Td-3

|

26.1

|

2.9

|

66.5

|

95

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tp-3

|

5.2

|

0.4

|

13.3

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted average, Savannas

|

5.6

|

0.6

|

17.8

|

24

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-altered

|

Rural:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

pasture (1)

|

11.2

|

65.5

|

12.2

|

89

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

secondary forest

|

30.9

|

112.4

|

22.8

|

166

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

agricultural fields

|

0.4

|

59.3

|

9.5

|

69

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

deforestation, 1998

|

0.0

|

271.2

|

43.2

|

314

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted average, Human altered

|

15.1

|

86.3

|

16.1

|

117

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban:

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Watercourses(3)

|

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total area (km2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Average of two pastures in the area of Apiaú,

Roraima. Live above-ground is the sum of grass and small herbs and

bushes. Dead above-ground encompasses

all plant material above the ground that is part of the mass of the pasture

and the mass of the former forest (logs, for instance). (Barbosa &

Fearnside, 1996).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) Methodology for

obtaining the biomass (live and dead)

above- and below-ground:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Da – Volume-expansion

method of Brown & Lugo (1992), corrected with the adjustment factors of

Fearnside (1992), modified for above-ground dead mass and below-ground live

mass.

|

|

|

Db -- Volume-expansion

method of Brown & Lugo (1992), corrected with adjustment factors of

Fearnside (1992), modified for above-ground dead mass and below-ground live

mass.

|

|

|

Dm -– Volume-expansion method of Brown & Lugo

(1992) corrected with the adjustment factors of Fearnside (1992), modified for above-ground dead mass and below-ground

live mass. (two values were considered : a) Roraima sedimentary plateau (10.7%) and b)

Parima mountains (89.3%)).

|

|

|

Ds -– Volume-expansion method of Brown & Lugo (1992)

corrected with the adjustment factors of Fearnside (1992), modified for

above-ground dead mass (two values were used (simple average): a) low chain

of mountains of the Guianan complex and b) dissected landscape of the Guianan

complex).

|

|

|

As - For lack of local

references, the value determined for ON was used.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fs - For lack of local

references, the value determined for ON was used

|

|

|

|

|

|

ON - Volume-expansion

method of Brown & Lugo (1992) corrected with the adjustment factors of

Fearnside (1992), modified for above-ground dead mass and below-ground live

mass.

|

|

|

SN - Volume-expansion

method of Brown & Lugo (1992) corrected with the adjustment factors of

Fearnside (1992), modified for above-ground dead mass and below-ground live

mass.

|

|

|

SO - For lack of references, the value for SN was used

(this was modified starting from the values obtained for "La"

(RADAM), and compared to the results of Silva (1993))

|

|

|

LO - Used as the average of three values to compose

the live and dead above-ground biomass: a) volume expansion; b) "bana

alta" (tall Amazon caatinga), by Bongers et al. (1985) and c)

Amazon Savanna, in Venezuela, by Klinge & Herrera (1983). For

below-ground biomass, the average of all the remaining of the groups was

used, to derive the percentage relative to the above-ground live biomass.

|

|

|

Ld - For lack of local

references, the value for Venezuelan “low bana" (Low Amazon Caatinga),

in Venezuela, of Bongers et al. (1985) was used

|

|

|

La - Obtained starting from the fieldwork of

Cavalcanti & Higuchi (in press.) in the south of Roraima in the landscape

denominated "Campina/Campinarana." The values of these authors for fresh

weights were converted to dry weight following the methodology of Carvalho et

al. (1995) and Higuchi et al. (1997).

The correction for the mass of other components was made using the

averages obtained by Bongers et al (1985) for the component "others” in

Venezuelan bana.

|

|

|

Lg - For lack of local

references, the value determined for Venezuelan "open" bana

(Open Amazon caatinga) by Bongers et al. (1985) was used.

|

|

|

rm - Estimate based on the

low stratum of the landscapes Sg, Sp and Tp.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sg – Above-ground biomassl (live and dead) from

Barbosa (1998) and, below-ground biomass, assumed as the average of the

results found by Castro & Kauffman (1998), for " clean " field

and campo sujo ("dirty" grassland) to a depth of 2 m, near

Brasília (3.78 times the live above-ground mass).

|

|

|

Sp (and Sa) – Above-ground biomass (live and dead)

from Barbosa (1998) and, below-ground biomass, assumed to be the obtained average of the results of

Castro & Kauffman (1998), for campo limpo ("clean"

grasslands) and campo sujo "dirty" grasslands to a depth of

2 m near Brasília (3.78 times the live above-ground mass).

|

|

|

Tp - Biomass above ground (live and dead) according to

Barbosa (1998) and, below-ground biomass, assumed to be the average of the

results of Castro & Kauffman (1998) for "open" cerrado

(central Brazilian savanna) and "dense" cerrado to 2-m depth near Brasília (2.55

times the live above-ground mass).

|

|

|

Td (and Ta) - The value of Fearnside et al. (nd) - for

above-ground biomass was assumed (29 t/ha) and was partitioned between live

and dead fractions, based on the average of the other values for savanna

found in the table. For below-ground

biomass, the method was the same as that adopted for Tp.

|

|

|

Pasture - Live above-ground biomass is the simple

average of two samplings in the area of Apiaú, Roraima (Barbosa &

Fearnside, 1996) (the value for dead above-ground biomass was considered to

be the same as that determined for secondary forest - both systems are

derived from deforestation; because pasture is a deforested landscape, the

below-ground biomass

was considered as an average of the below-ground biomass of all forest systems).

|

|

|

Secondary forest – Above-ground biomass is assumed to

be the value determined for 6-7 year-old secondary forest in the area of

Apiaú, Roraima (Fearnside et al., nd) (dead biomass was considered to be

original-forest remains in the same study and, below-ground biomass is calculated

using the same relationship as that described above for pasture).

|

|

|

Agricultural fields - Assumed to be the same as that

given by Fearnside (1997a) for "farmland" (the value for above-ground dead biomass

was considered to be the simple average of the dead above-ground mass of

pastures and secondary forests and the live biomass of newly deforested areas

- all considered transformed environments.

|

|

|

Recently deforested - Considered as the biomass

present at the time of felling. This was derived from the values determined

for Ds, ON, Fs, LO and As. The dead above-ground biomass is that calculated for this group

plus the pre-existing litter (fine and coarse).

|

|

For the non-forest oligotrophic

systems (grasslands, campinas and campinaranas), besides the RADAMBRASIL

timber volume data, we used existing studies in similar eco-regions in

Venezuela (Bongers et al., 1985; Klinge and Herrera, 1983) and a study carried

out in the south of Roraima by a team from the Tropical Forestry Department at

INPA in 1992 (Niro Higuchi, personal communication). The values for total biomass varied from 52

t/ha to 117 t/ha for these systems. The

values for other non-forest eco-regions (savannas), were adjusted based on

studies of R.I.B. that are underway since 1994 for estimation of emissions of

greenhouse gases from burning in Amazonian savannas. To estimate below-ground biomass in savannas

we used the proportions obtained by Castro and Kauffman (1998) in the cerrado

savannas of central Brazil. In general,

the total biomass (above- and below-ground) of these systems was 13-95 t/ha,

depending on the proportion of trees present in each habitat.

Estimate of the pre-existing

biomass in the human-affected systems were derived as follows: (a) pastures we

used the simple average among two pastures (7 and 9 years of age) studied in

the area of Apiaú, Roraima, by Barbosa and Fearnside (1996); for above-ground

biomass we considered the sum of the mass of grass and small non-woody

herbs. For the above-ground biomass

killed we considered the same study and determined the average of the whole

mass of the forest residues found in the two pastures; for the below-ground

biomass we considered the existing mean proportions in the other transformed

systems to determine the percentage with respect to live above-ground biomass;

(b) secondary forests: we used the results obtained by Fearnside et al. (nd) in

a five-year-old secondary forest in the area of Apiaú, Roraima; (c)

agricultural fields: we assumed the value determined by Fearnside (1997a) for

live above-ground biomass and we used the same proportional result (live/dead)

for dead above-ground biomass in the pastures at Apiaú; (d) 1998 deforestation:

we considered as the present biomass at the time of cutting (before the burn);

this value was estimated by weighing, based on area of each of the other forest

types that are subjected to deforestation in Roraima. The results for total biomass in these

systems were: 89 t/ha (pasture), 166 t/ha (secondary forest), 69 t/ha

(agricultural fields) and 314 t/ha (recently deforested areas).

Forest arboreal biomass killed by

the Fire

To survey the biomass killed in the

different forest types we carried out post-fire studies in three areas affected

by the fires: (a) Apiaú/Ribeiro Campos, (b) Trairão/Tepequém and (c) Paredão,

all in the ON type (area of ecological tension or ecotone and contact between

ombrophilous and seasonal forests). For

the arboreal species above 10 cm diameter at breast height (DBH), we established

seven 750-m2 transects, three of which were

at the first site, three at the second and one at the third. Each transect was divided into 6 quadrats of

125 m2 (5 m × 25 m), separated by a distance of 20 m. In each quadrat we measured the DBH of all

individuals killed (dry cambium and/or crown with dry leaves) and we applied

the general formula for biomass determination (fresh weight) for tropical

forest trees given by Carvalho et al. (1995) and Higuchi et al. (1997, 1998).

The value was adjusted for dry weight (t/ha) following the

recommendations of these authors. With

this, we reached the result of 5.8 t/ha for the 2173 individuals killed with

DBH below 10 cm and 17.4 t/ha for the 46 individuals killed with DBH above 10

cm (Table 4).

[Table 4 here]

|

Table 4 - Mortality of

individuals (number/ha) and of above-ground arboreal biomass (t/ha)

determined in three studies after the burn in Roraima.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Simplified

diameter classes (cm)

|

Above-ground

arboreal average

|

|

|

|

Parameters

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

< 5

|

5-10

|

> 10

|

Individuals

|

Biomass

|

Source

|

|

|

|

no./ha

|

t/ha

|

no./ha

|

t/ha

|

no./ha

|

t/ha

|

no./ha

|

t/ha

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total individuals or

biomass(1)

|

2,120

|

5.6

|

307

|

19.9

|

585

|

219.7

|

3,011

|

245.2

|

|

|

|

Dead

|

|

1,933

|

3.0

|

240

|

2.8

|

46

|

17.4

|

2,219

|

23.3

|

This study

|

|

(%) mortality

|

91.2

|

54.2

|

78.3

|

14.1

|

7.9

|

7.9

|

73.7

|

9.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total individuals or

biomass(2)

|

|

|

340

|

|

425

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dead

|

|

|

|

122

|

3.0

|

68

|

16.1

|

|

|

Santos et al.

(1998)

|

|

(%) mortality

|

|

|

35.9

|

|

16.0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total individuals or biomass

|

|

|

|

|

616

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dead

|

|

|

|

|

|

50

|

|

|

|

Brazil, IBAMA

(1998)

|

|

(%) mortality

|

|

|

|

|

8.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) For DBH $ 10 cm in the following

locations: Apiaú/Ribeiro Campos, Trairão/Tepequém and Paredão; for DBH <

10 cm in the following locations: Apiaú/Ribeiro Campos.

|

|

(2) Area of

Apiaú/Mucaja.í

|

|

(3) Includes palm trees.

Evaluation of the areas of the arc of fire connecting the areas of Roxinho,

Caracaraí, Apiaú, Pacaraima and Trairão.

|

These values are similar to the

16.1 t/ha determined by Santos et al. (1998) for individuals killed above 10 cm

DBH in the Apiaú area and they are similar to the results of the survey of

individual mortality that the IBAMA teams carried out in five areas affected by

the fires, which found a mean of 50 dead individuals/ha with DBH above 10 cm,

including palms (Brazil, IBAMA, 1998). However,

the variation in the values distributed among the diameter classes and sites

reflects a great variation among the areas studied, in spite of all of the

areas being classified as belonging to the same forest category (ON). With respect to other studies carried out in

similar situations, our percentage value for individual mortality (7.9% for DBH

above 10 cm) is 5.5 times less than to the 44% found for burned areas derived

from forests that has been selectively logged in Paragominas (Holdsworth and

Uhl, 1997) and, 7.6 times less than the 60.3% mean mortality found eight months

after the burn at four other sites in Paragominas county in already disturbed

forest areas (Kauffman, 1991). In terms

of total above-ground arboreal biomass killed, our values represent less than

half of the 50 t/ha of dead mass for a light fire (area burned only once)

studied by Cochrane and Schulze (1999) south of the town of Tailândia,

Pará. Although differences exist between

natural forest structures and those disturbed by human action, the comparisons

mentioned above suggest the need for continued post-burn monitoring in

Roraima. Dramatic biomass change and an

increased number of individuals killed are expected, even in little-affected

systems.

Arboreal biomass killed below 10 cm

DBH was estimated by counting the individuals (dead and alive) in two 375-m2

transects (3 quadrats of 125 m2) established at Apiaú and Ribeiro

Campos. Individuals were divided into

two categories: (a) smaller than 5 cm DBH (including all seedlings and saplings

of different heights) and (b) 5-10 cm DBH.

Biomass in these two categories was estimated based on the proportion of

the individuals present (dead and alive) and the values determined for biomass

of trees below 10 cm DBH in the estimates described above for total biomass by

forest type.

Formation of Charcoal

To estimate the amount of charcoal

formed by the fire in the primary forest systems, we established 20 1-m2

quadrats, at the Apiaú and Ribeiro Campos sites. The quadrats were distributed as follows: (a)

11 where the fire was considered to be of high intensity, (b) 5 in habitats

with damage of average intensity and (c) 4 in habitats with damage of low intensity.

In each quadrat all pieces of charcoal on the ground were collected. Wet weight was measured and dry weight was

determined later by drying the material to constant weight in an electric oven

at 105oC. We considered the

values found by intensity of burning in order to establish a mean result for

each block and for the burned area as a whole.

The mean result was 229.7 kg of charcoal formed per hectare affected by

the fire in the forest areas (Table 5).

This value is, on average, 0.089-0.104% of the total above-ground

biomass in the forests (dense and non-dense) of Roraima. This charcoal formation percentage differs

substantially from the values found for burns of transformed systems such as

pasture (2.5-3.8%), secondary forests (0.6 - 2.0%) and recent clearings (1.9%)

(Barbosa and Fearnside, 1996; Fearnside, 1997a,b;

Fearnside et al., nd).

[Table 5 here]

|

Table 5 - Formation of

superficial charcoal (t/ha) due to the fires in forest systems of Roraima

(1997-98) by fire intensity zone and block.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forest burn

intensity category

|

Simple average

by Intensity (kg/ha)

|

Area

effectively burned in each Block(2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Block 1

|

Block 2

|

Block 3

|

Total

|

|

|

(km2)

|

(km2)

|

(km2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HIGH (1)

|

258.7

|

1,208

|

5,278

|

2,702

|

9,817

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AVERAGE

|

51.3

|

793

|

459

|

235

|

1,487

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LOW

|

9.8

|

51

|

27

|

11

|

90

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Weighted

average

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by block

|

-

|

172.3

|

241.0

|

241.2

|

229.7

|

|

|

(kg

charcoal/ha)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) We weighted the average

for the high-intensity zone because 6 quadrats were sampled at terra-firme

(upland) locations (173.9 kg/ha in 84% of the affected area) and 5 in

foothill locations (707.3 kg/ha or 16% of the affected area).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) The value here used was

determined the method of the fire-impact zones (11,394 km2).

|

|

|

|

Burning efficiency

For estimating burning efficiency

in forest we divided the plant material into three groups: (a) fine litter:

leaves and twigs less than 2 cm in diameter that had fallen on the forest

floor, (b) coarse litter: logs and dead branches on the ground with diameter

over 2 cm and (c) other components: other plant categories that are neither

litter nor trees. The percentage

estimates of burning efficiency were based on the average of the measurements

made by Uhl et al. (1988) in experimental burns in San Carlos (Venezuela) and

with the data collected by IBAMA at Trairão and Roxinho (Brazil, IBAMA,

1998). The largest and the smallest

values were distributed among the forest burn intensity zones and, on average, they were between 4.5% for the coarse litter in the

low-intensity zone and 97.6% for fine litter in the high-intensity zone (Table

6). For the savannas we used data from

the studies that R.I.B. has been carrying out since 1994 in the study

area. The values were lumped into a

single category of burning intensity, ranging from 28% to 94.6%, depending on

the biomass class. For human-altered

environments burning efficiency ranged from 11.9% to 97.6%.

[Table 6 here]

|

Table 6 -

Burning efficiency (%) by fire-intensity zone (forest) and by landscape type,

|

|

|

due to the fires in Roraima (1997-98).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fine litter

|

|

Coarse litter

|

|

Other

Components

|

|

|

Category

|

Code

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low

|

Average

|

High

|

|

Low

|

Average

|

High

|

|

Low

|

Average

|

High

|

|

|

|

Da-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Db-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dm-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forest

|

All

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

(Dense and

Non-dense) (1)

|

Types

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-dense

forest

|

All

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

As-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fs-0

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

ON-0

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SN-0

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SO-0

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LO-0

|

69.3

|

83.4

|

97.6

|

|

4.5

|

39.2

|

73.8

|

|

4.5

|

28.0

|

51.5

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-forest(2)

|

Ld-0

|

-

|

-

|

83.4

|

|

-

|

-

|

39.2

|

|

-

|

-

|

28.0

|

|

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

La-0

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

Lg-0

|

-

|

-

|

85.5

|

|

-

|

-

|

22.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

59.4

|

|

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

-

|

-

|

|

|

|

|

rm-0

|

-

|

-

|

85.5

|

|

-

|

-

|

22.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

59.4

|

|

|

|

Sg-0

|

-

|

-

|

81.9

|

|

-

|

-

|

18.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

80.9

|

|

|

|

Sp-0

|

-

|

-

|

84.2

|

|

-

|

-

|

22.9

|

|

-

|

-

|

63.7

|

|

|

|

Td-3

|

-

|

-

|

85.5

|

|

-

|

-

|

22.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

59.4

|

|

|

|

Tp-3

|

-

|

-

|

90.4

|

|

-

|

-

|

26.3

|

|

-

|

-

|

33.7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-altered

|

Pasture

|

-

|

-

|

45.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

11.9

|

|

-

|

-

|

82.1

|

|

|

|

Secondary

forest

|

-

|

-

|

91.3

|

|

-

|

-

|

31.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

80.0

|

|

|

|

Agricultural

fields

|

-

|

-

|

91.3

|

|

-

|

-

|

21.8

|

|

-

|

-

|

81.1

|

|

|

|

Deforestation(3)

|

-

|

-

|

97.6

|

|

-

|

-

|

30.0

|

|

-

|

-

|

75.7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Urban

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Watercourses(3)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total area (km2)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(1) We

considered a general average for all types of forest systems.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) For non-forest systems

we took in consideration the values determined for the local savannas; for

the oligotrophic areas values are based on the biomass present in each

system.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(3) Burning efficiency for

thick litter and other components in "deforestation" was considered

as the same value observed in Altamira by Fearnside et al. (1999). For fine litter, we used the simple average

of the results found by the same authors in Manaus and Altamira.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(4) Non-forest and

human-altered systems were considered to always be in zones of high intensity

because these areas could not be differentiated into other categories due to

the great impact that the fire provoked in these systems.

|

|

|

Concentration of Carbon

The concentration of carbon (%C) in

the vegetation categories of forest systems was estimated based on the

measurements of Barbosa and Fearnside (1996) and Fearnside et al. (nd) in wood

pieces and other forest components found in pastures and secondary forests in

the Apiaú area. For the carbon

concentration in the savannas, we use the results obtained by R.I.B. in his

studies of greenhouse gas emissions from burning and decomposition in savannas

in Roraima. The results ranged from

33.0% C for litter of grassy-woody savanna up to 64.4% C for charcoal found in

the different environments (Table 7).

[Table 7 here]

|

Table 7 – Mean carbon

concentration (% C) in the ecological systems of Roraima.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Category

|

Code

|

Dead trees (above- and

below-ground)

|

Litter

(fine + coarse)

|

Other

components

|

Charcoal

(long-term pool)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forest

(dense and

non-dense)

|

All forest

types

|

48.2

|

39.8

|

48.2

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Non-forest

|

Ld-0

|

48.2

|

39.8

|

48.2

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

La-0

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lg-0

|

46.7

|

36.0

|

38.8

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

rm-0

|

46.7

|

36.0

|

38.8

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

Sg-0

|

47.2

|

33.0

|

36.0

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

Sp-0

|

46.8

|

36.7

|

40.2

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

Td-3

|

46.7

|

36.0

|

38.8

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

Tp-3

|

46.1

|

38.4

|

40.2

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-altered

|

Pasture

|

44.5

|

47.8

|

43.8

|

64.4

|

|

|

|

Secondary

forest

|

44.5

|

42.9

|

45.5

|

63.2

|

|

|

|

Agricultural

fields

|

44.5

|

45.4

|

44.6

|

63.8

|

|

|

|

Deforestation

|

44.5

|

45.4

|

44.6

|

63.8

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fate of Carbon Affected by the Fire

The total mass of carbon affected

by the fires in Roraima in 1997-98 was 45.63 million tons of carbon (t C). This carbon followed three different

pathways: (a) carbon emitted instantaneously to the atmosphere by combustion:

18.90 million t C or 41.4% of the total, (b) carbon stored in the form of

charcoal on the ground in the affected systems: 0.52 million t C or 1.1% and

(c) decomposition of plant material killed by the fire (mainly trees): 26.36

million t C or 57.4% (Table 8). Of the

total affected carbon, 72.1% (32.9 million t C) can be attributed to primary

forest systems that were exposed to fire.

The systems that contributed least were the oligotrophic formations

(other non-forest systems) with 2.7% of the total affected carbon (1.25 million

t C).

[Table 8 here]

|

Table 8 - Fate of carbon

affected by the burning of vegetation in Roraima (1997-98).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

System

|

Combustion

|

|

Charcoal

|

|

Decomposition

|

|

Total

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(106 t)

|

(%)

|

(106 t)

|

(%)

|

(106 t)

|

(%)

|

(106 t)

|

(%)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Forests

|

12.78

|

67.6

|

0.19

|

35.9

|

19.93

|

75.6

|

32.90

|

72.1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Savannas

|

2.34

|

12.4

|

0.0006

|

0.1

|

4.80

|

18.8

|

7.14

|

15.7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other

Non-forest systems

|

0.26

|

1.4

|

0.0003

|

0.1

|

0.99

|

3.8

|

1.25

|

2.7

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-altered

|

3.52

|

18.6

|

0.33

|

64.0

|

0.48

|

1.8

|